Bettmann/Getty Images

Senator Elizabeth Warren is leading the charge to gain control of important private-sector patents.

Over the weekend, I took my daughter and her best friend on a day trip from Northern Virginia to Hico, West Virginia. In a matter of 120 minutes, you pass from one of the statistically wealthiest areas in the United States to some of the most destitute roadside neighborhoods you’ll see in the region. The friend asked why it's like this in West Virginia, and all I could think to say in response was, “All your friends back in Northern Virginia, what do their parents do for work?” It didn’t take her long. She responded, “Oh like mostly the Pentagon, Boeing, and I know a few kids whose parents go out to Quantico.” That’s not an answer to why West Virginia is more poor, but it does explain the wealth of Northern Virginia. Connection to the federal government is an economy of its own, and the tentacles of federal money cover 61 square miles and ten counties known as the DMV.

Say what you will about Apple, but it’s a company that frustrates the U.S. federal government with its dogmatic approach to consumer privacy and walled garden systems. We need more of that, not less.

Billions of dollars float through Virginia and Maryland in the form of federal grants for research and development related to technology, medicine, education, and much more. What that means is that there is seldom a microchip, vaccine, weapons system, satellite, or AI tool that hasn’t benefited directly or indirectly from taxpayer dollars somewhere in its development.

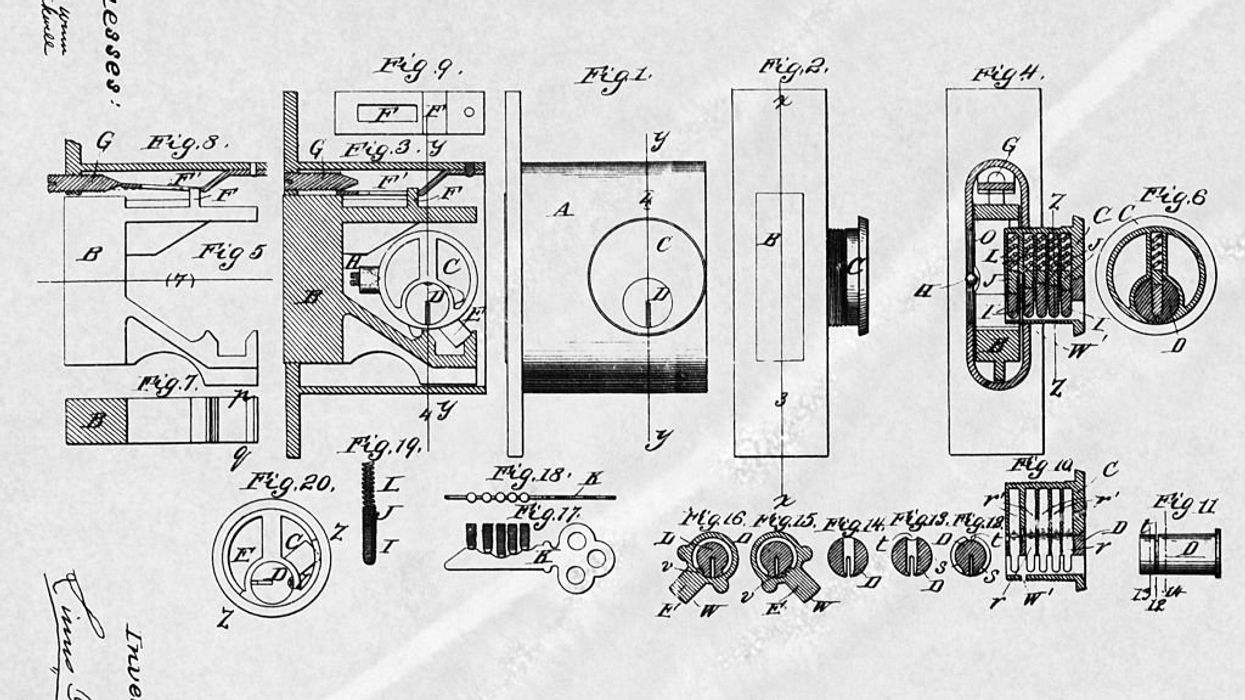

While this arrangement between the public and private sectors has historically been a boon to the United States in a global economy, there is a real risk to American innovation if certain norms are busted by lawmakers looking to score political points. The federal government could seize control of most patents in AI, microchip tech, and pharmaceuticals using a legal tool known as “march-in rights.”

As recently as last week, the Biden administration is under pressure from Democratic lawmakers to use march-in rights to lower pharmaceutical drug prices. This authority, granted by the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980, empowers the government to take over patents on products developed using federal funding if those products are not reasonably available to the public.

Senators Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Angus King (I-Maine), along with Rep. Lloyd Doggett (D-Texas), sent a letter to Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra and Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo, urging them to quickly finalize the guidance on federal "march-in rights."

These Democrats think the use of march-in rights is a straightforward way to lower consumer drug prices and would have observers believe the political upside is a mere coincidence in an election year. The norms around “march-in rights” are essential.

This power exists but has never been used before, despite several petitions for the government to do so in recent decades. Like most powers the federal government acquires, there are good reasons it came to pass. The Bayh-Dole Act was originally designed to encourage the commercialization of technological innovation by allowing universities and small businesses to retain patent rights on products developed with federal funding.

This led to the development of many new technologies and medicines ranging from a chemotherapy drug for cancer patients called Taxol to the common allergy medication Allegra and even next-generation firefighting drones.

A federal agency can theoretically leverage march-in rights and grant licenses for a product funded by taxpayer dollars if these four conditions are met:

It should come as no surprise that the Biden administration is not keen on letting the market determine drug prices. The Biden administration recently debuted a framework for how it might make use of the Bayh-Dole Act to start setting prices on a narrow subset of drugs.

Most consumer drugs on the market are the result of multiple patents held by developers rather than researchers funded in part by the National Institutes of Health. The latter scenario is one with the ever-present potential of government intervention and seizure of the patent.

That potential is what spooks innovators across the most vital sectors in the American economy. In ventures where the risk is high, firms are less inclined to make major investments. A fine example of this is when the Federal Communications Commission introduced regulatory uncertainty into the broadband sector, which led to a 10% decline in private-sector investments toward broadband. Consumers nationwide saw reduced network coverage and reliability.

This can happen in the artificial intelligence space, microchips, and cloud computing. Federal dollars are everywhere in these industries. Large companies like AMD, Intel, and Nvidia receive federal funding for AI or semiconductor research and could be subject to march-in rights once the dam breaks on its use. The government might justify seizing patents if it determines that the public interest or national security is at stake.

Consider the situation if China were to finally invade or blockade Taiwan, a small neighbor that produces 90% of the global supply of advanced chip technology. This would be a real emergency for consumer products and sensitive government tech used for national security. The same goes for the global race to develop AI technology using federal funds for R&D. If AI is produced and isn’t being deployed in a way that benefits the United States during a potential foreign war, the government could step in using march-in rights on products created through the Bayh-Dole Act.

In these scenarios, with all the norms restricting the government’s use of march-in rights to seize patents shattered, you could see a dramatic decline in the vitality of American tech innovation. Even worse, you could see the government attempt to actively control these patented technologies and award them to domestic partners who will be the most cooperative with the government when pushed.

Say what you will about Apple, but it’s a company that frustrates the U.S. federal government with its dogmatic approach to consumer privacy and walled garden systems. We need more of that, not less.

With so much next-generation technology being developed in the D.C. area with government dollars as a subsidy, we must strongly resist calls in Congress to wield march-in rights inappropriately. Drug prices should be lower, but in market economies, there are better paths to take such as streamlining the approval of generics, expanding the use of Health Savings Accounts, and importing prescription drugs from foreign competitors.

Stephen Kent