General Photographic Agency/Getty

This is a piece all about the art of flourishing on the digital frontier. It’s right there in the mission statement. Maybe you’ll be able to tell me how to thrive if any digital establishment can kick us out in a minute or, worse, if we can’t even find the door to the place.

On the collective level, we’re experiencing a season of intense volatility related to social media platforms, so naturally, I found a great source of amusement in the badass free speech warriors going on a tear about being censored by Big Tech – heh heh heh, dorks – until a popular trio of left-leaning podcasters was suspended on Instagram for nebulous “rules violations.”

Big Tech does suck when it censors the people you like.

The podcast (Conspirituality) was still produced and released since it did not rely on Instagram to reach its audience. Still, the hosts needed to be above, reflecting on the air about the emptiness creeping up on them. Thousands of curated interactions had been wiped out along with the community. They might as well never existed. Was there any point in settling down if your estate could be blown apart in a minute from now, time and labor wasted on a body of non-work, nothing to hold on to, nothing to show for yourself?

Earlier this year, I was removed from a women-only writing group. It was possibly meant as a private space to unwind and swap material, and if I could recover up to five months of daily conversations, I’d be more specific about the group’s stated intent.

This was a personal first. I’ve been let go; I’ve been muted, I headlined a commercial flop: I had never been evicted from a space with the dismissal being couched in corporate Human Resources lingo – fairness, concern, engage, appreciate it.

It ended in a wall of text as a direct message on a Friday morning. The woman who invited me warned me of a possibility: I may take you and R. out of the chat. […] You both don’t seem to want to engage with the others’ work. [---] Let me know if this is unfair to you.

I was busy, maybe on deadline, maybe wrangling a minor fire, irrelevant, so I typed, oh, let me think about it, and I moved on, pausing to wonder how I could make more of an effort; I had been absent from the last Zoom calls – but any attempt would have been in vain. Come Saturday morning, the group chat icon wasn’t there.

(As for the other woman on the chopping block – R., a published author – she didn’t get the courtesy warning shot, just a cool postmortem email.)

This was a personal first. I’ve been let go; I’ve been muted, I headlined a commercial flop: I had never been evicted from a space with the dismissal being couched in corporate Human Resources lingo – fairness, concern, engage, appreciate it.

The physical side of this removal was dull and survivable, if not expected. A colleague reached out to let me know there had been no discussion beforehand; another said she was saddened it ended that way. Standard procedure overall: say what you will about its ethos, woman-on-woman community policing is excellent at disappearing people. The technical side of the removal was a brand-new beast. You catch a block; you can still see the outline of what you’re denied access to – a description of the person or the collective. You can’t tell what they’re doing, that’s all. If you get banned from a venue, the building is there. You get locked out of a group; there’s nothing to see. This never happened.

Imagine a neighborhood store disappearing on you in the blink of an eye. Did you hallucinate the store, the bell chiming at the doorway?

Hard to fathom how it was the same woman writer who had approached me first, showered me with excessive praise, and offered up the guest room of her city apartment, in case I needed a change of scenery, two or three weeks before hitting the erase button.

Had I come to rely on the woman writer as a friend, I would have been hurt: had I relied on the space for work contacts or a Cursed flavor of validation stemming from in-group encouragement, I’d be face down in a ditch. (Nope.) In five days, the loneliness faded out enough for the experience to be framed as the bump in the road it was, safe to revisit over texts with acquaintances, in the small language one should use for a case of food poisoning after the fact. Guess what happened? LOL. LMFAO.

Being born outside the United States, I used to be wary of the “toxic white woman” trope – call her Karen, call her Becky, she’s a crossover punching bag, left-left-left-right-left, the red thread of American discourse for a decade now. Surely this is too convenient, you think. Talk about broad generalizations, you think.

And then one day, you’re in the Sunken Place. How about that! LOL. LMFAO. Karen called the manager.

An accomplished writer and critic whose production outlived multiple viral cycles, in the 2023 essay “The Creative Underclass is Still Raging,” deBoer looks at the waves of anger and resentment permeating online conversations, and he zeroes in on a perpetually over-reacting type:

“I’m talking about people, almost always college-educated, most gainfully employed, who have unrealized dreams in creative industries like movies, novels, journalism, music, essays, TV, podcasts. They have positions in the world that are, by international or historical comparison, quite comfortable. […] Sometimes these people have actually tried and failed in various creative endeavors - gone to film school, sent their manuscript out to agents, bought an expensive microphone and ring light for their YouTube channel, spent a year begging people to like, share, and subscribe to their podcast. My sense, though, is that many of the people I’m talking about have never actually made an honest try at a creative field, perhaps too embarrassed to dream big and fail. They are nevertheless possessed of a deeply-ingrained cultural expectation that they’re supposed to desire more than middle-class stability and the fruits of contemporary first-world abundance.”

The easiest way to dismiss one’s work is to frame the artist as “an amateur,” some clueless hack who keeps falling into golden rivers, meritocracy be damned. And the original use of the term “creative underclass” reflected this disparity – on paper. Vanessa Grigoriadis wrote about it back in 2007 to explain the success of Gawker in its first incarnation, a gossip website powered by the suicide pact that was the alliance between the staff writers and the anonymous comment section. (Staff posted, “Lindsay sucks!” the comment section went, “Why is Lindsay STILL getting work instead of SOMEONE WHO DESERVES IT.”) So what you had was a bunch of professional haters feeding the trolls with a wide variety of people who might have been sexier, more ambitious, more productive, and plain earnest in their wish to become famous.

Only a select few use their time online to describe a present shaped by poverty – rent high, student loans bad, saved you a click: most are blessed with stable, well-paid jobs, significant wealth, or both.

The perennial amateur who wants to be vindicated about his or her lackadaisical approach to work is the sort of individual deBoer nails in the essay, the desk-job adult with all the browser tabs open, the podcast playing in the background:

“They don’t do a single thing that’s physically taxing, risk no injury in their work other than carpal tunnel, and are often minimally supervised.”

Material circumstances leave them free to entertain a lifestyle fantasy spun around the desire to be celebrated as a culture maker. They flit and cycle through all formats of media production without laying the groundwork for a single one. And because “finishing what you start” is what passes for a relatable stumble in 2023, you can play that angle up to merge with the crowd – oh, I’m so bad at this. I’m so so bad at focusing. I’m bad with tech; I’m bad with money, I’m bad with social cues.

Christ alive, Melissa, name one thing you’re good at.

The Girl section of the creative underclass makes everything about comfort.

Only a select few use their time online to describe a present shaped by poverty – rent high, student loans bad, saved you a click: most are blessed with stable, well-paid jobs, significant wealth, or both. They’re accustomed to getting meals, groceries, and personal items delivered to their door. They subscribe to dozens of streaming services, they call an Uber to go anywhere, and they can pick and choose every day from hundreds of separate outfits, accessories, and make-up products. They spend eight to twelve hours on social media, switching between the fearful monitoring of who said what now and the barrage of private messages devoted to what’s happening on main and in another private chat. They look into renting storage units for the extra stuff they can’t bring themselves to part with.

They demand any creative endeavor to prioritize “play” and “fun.” Like they’ve all just been rescued from a witch’s house and need to be eased back into non-captive life. Blame the wellness manuals that put a premium on “being kind to yourself,” blame Julia Cameron for the bank she made off The Artist’s Way, stare at the purple blob rising up from the pastel terminology of fairness and safety as it fuses with the online aesthetics of the stay-at-home mother who yearns for more meaning, more time, more candy for breakfast.

In this house, give yourself permission to create.

Unless you were born in an abattoir, “permission to create” is the desire to be told you are a nice person, God loves you, spend that money. And it’s always a pastel God, too. Please, Cthulhu, show up in the chat. Once. Just once. For all their advantages, women with unfulfilled Art dreams run into a peculiar absence of urgency. They don’t need to write, draw or build much. (They love to talk about inspiration.) You find yourself spelling out a basic work ethic for them: point of view, persistence, time on the mat, look at the facts and adjust accordingly, keep up a production rate, pick three, and off you go.

I doubt the basics are ever spelled out like that.

The creative underclass is alive because it keeps itself alive – as all blurry, boundary-light entities are wont to do – the reason it’s tolerated, however, and allowed to flourish, lies in its willingness to liberate the money somebody’s been making. Not MFA money, no, five dollars here, four hundred there. Reading fees; application fees. Online courses. Screenwriting manuals telling you procrastination is the best part of the work, and you should treat yourself by wasting a day in a store and buy a whiteboard. Otherwise, respectable institutions sell “intensive classes” to be held in locales branded as worth the trip alone. Learn stand-up comedy in magical Santa Fe! Harness the power of yoga and journaling in Portofino! Give us three thousand dollars to study in Paris for five days! Granted, it could be a stealth Leaving Las Vegas situation, and people do try to kill themselves with abundance in the privacy of their homes, yet, take a look at the class photos (obligatory): nine out of ten participants are women, most of them white. Pretty things in dire need of an alibi for the eye-popping price tags on vacations they were gonna be taking anyway. You deserve it. You work so hard. You deserve to be inspired.

(Funny, some folks would benefit from a class. The nameless person who slaves over a first novel clocking in at 160.000 words, the adult who stokes the home fires daydreaming about a seven-way auction, only to discover through a cursory 30” Google searches their baby should get sliced in half to be considered sellable goods. This person might have wanted to buy the “Publishing 101” course from a general-interest platform. So why didn’t they? That’s a matter of wanting to be proven right.)

Regarding the market, Western women are framed as consumers first. Art, fashion, anti-fashion, beauty, sensory deprivation tanks. Under that respect, American women are a parallel universe where Caligula levels of money are set on fire. You don’t believe it until you see it happen in real-time and blink. You say, “Why on Earth are you spending money on a sensory deprivation tank, Melissa? Don’t you have a movie to make,” and instantly become every disapproving male authority figure they ever met.

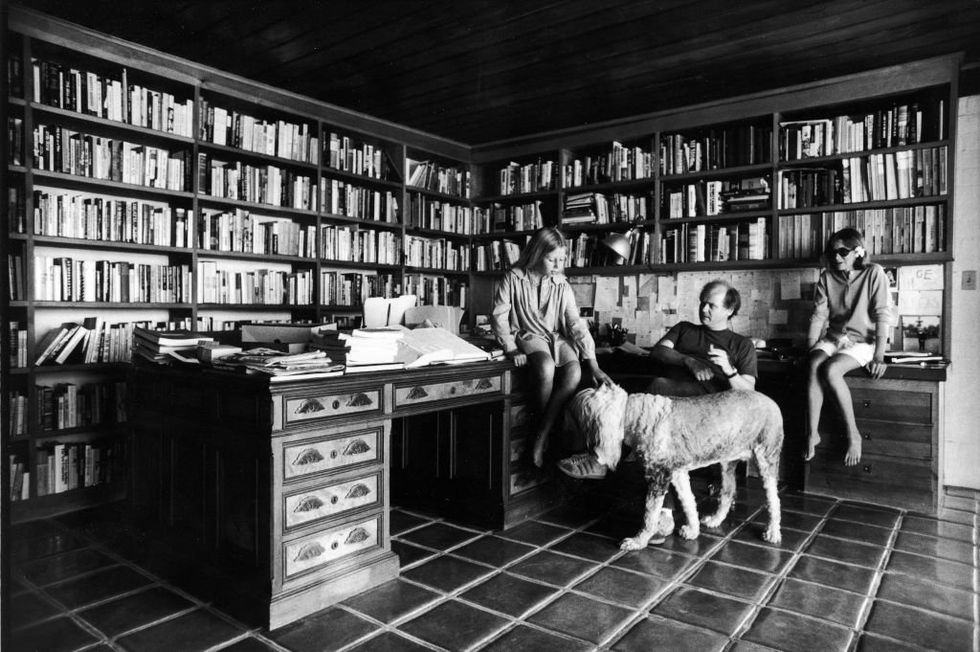

There’s no living with a woman who frames herself as a puella eterna. And it’s a part they can perform well. A five PM stroll through their online personae tells the story of the view from their perch, the fascination with writers’ desks, and the casual shift to painting/ceramics / mixed media. For sure, it paints a common portrait of the girl self, the artist as a playful, loose spirit.

About the persona. For ages, the safest method to create yourself was to become a Punisher: the know-it-all who lives to dunk on journalists, experts, and pundits. Freddie deBoer is especially miffed at the attacks on journalists, but long before it reached the mainstream, this strategy was fine-tuned in movie discussion boards and fandom circles. Say director bad, America bad, boom boom; you gained an audience hungry for a takedown.

As the fate of Gawker 1.0 shows, pivoting to “original, serious content” is a non-starter when you’ve built your reputation on mockery – you are the prisoner of an audience you loathe.

You’re gonna start with a different face. Most male artists devote a lot of time to their online face, and they’re devastated if they lose it, but the persona is sharper, the lines harder. The bad boy, the goofball, the optimist, the reject, the wrestler, the veteran who’s seen it all (can’t shock him). Male writers will tell you how many words they got down in an average week, save and share every paragraph they’re happy with, and male directors will update you on their tiniest wins of the day, look; they are doing shit.

And they finish it.

Screenwriter C. Robert Cargill (Dr. Strange, The Black Phone) habitually reminds his followers of the importance of commitment. He keeps it simple: “A finished thing can be fixed. A finished thing can be published. A finished thing can be made into a movie.”

Cargill is a busy guy. He taught himself how to rise from the pages of Ain’t It Cool News to regular acclaimed work. He’s an affable Texan, quick to laugh: his advice should provide a friendly off-ramp for all the creative underclass folks who want to give it “a honest try.”

But do they want to?

This is the same social-media-driven Internet that made burnout a sizzling hot cultural issue. Remember burnout? It was all the rage in 2018. It made people’s careers in 2018. How to avoid burnout, Are you getting burnout? Recover from burnout, Signs you might be headed toward cataclysmic brain-smashing burnout. And the loudest howls of pain came from the desk job ladies lamenting they couldn’t bring themselves to carve the time out for the Reading of Books, never mind the Making of Art.

Melissa: there’s no twelve-hour shift at the paragraph factory; come on. You can’t talk in stock sentences and expect me to nod. Carve out the time. As opposed to when we were immortal and time bent to our will? Share collective grief over random issues humanity has dealt with for centuries. Repeat the last words on your screen. Uphold Blob Thought.

Return readers are familiar with a phenomenon: the rush to flock towards the right side, the side winning at the moment. The dropping of likes, the drawing of battle lines. The inability to make up one’s mind without checking the general consensus.

For this, we’ve had all the names.

We’ve had the Maw (“the aggregate of opinions of paid-up journalists and writers and pundits”), the Blob (originally “the foreign policy establishment”), the Borg, the Tomatometer, the Monster. We can have “the Void” too – loss of autonomy as the inevitable outcome you are led to wish for.

You think you’ve seen manufactured consent, wait until you get a load of the art people who sincerely believe getting their mutuals to click on their links is what matters most.

Suppose grandiosity and defeatism are twin flames fueled by the same terror of failure. In that case, it must be remarked how “failure” in the Twenties has become “not receiving (x) amount of views from an audience comprised entirely of your peers.” Forget about old-world crash tests – failure to sell your art, failure to secure funding, financial ruin; most aspiring artists don’t even want to get paid for their work, and if they do, they shut up about it. Money enters the equation, and work becomes, you know. Work.

Before the group chat disappeared, I had been drifting out. To a civilian friend, I caught myself explaining – always a bad sign – how the people were really lovely, but the group felt more and more like the Creative Underclass Girl Internet in a microcosm: indulgence, you do you, willful blindness to the market, any market. My production rate was winding down to a purple string of bubble tape because of the mass of digital clutter (the group chat boasted hundreds of DMs per day, a conservative 30% devoted to fashion, skin care and sensory deprivation tanks) and the eventual pre-school shadow looming over the proceedings: share your toys, whose turn is it.

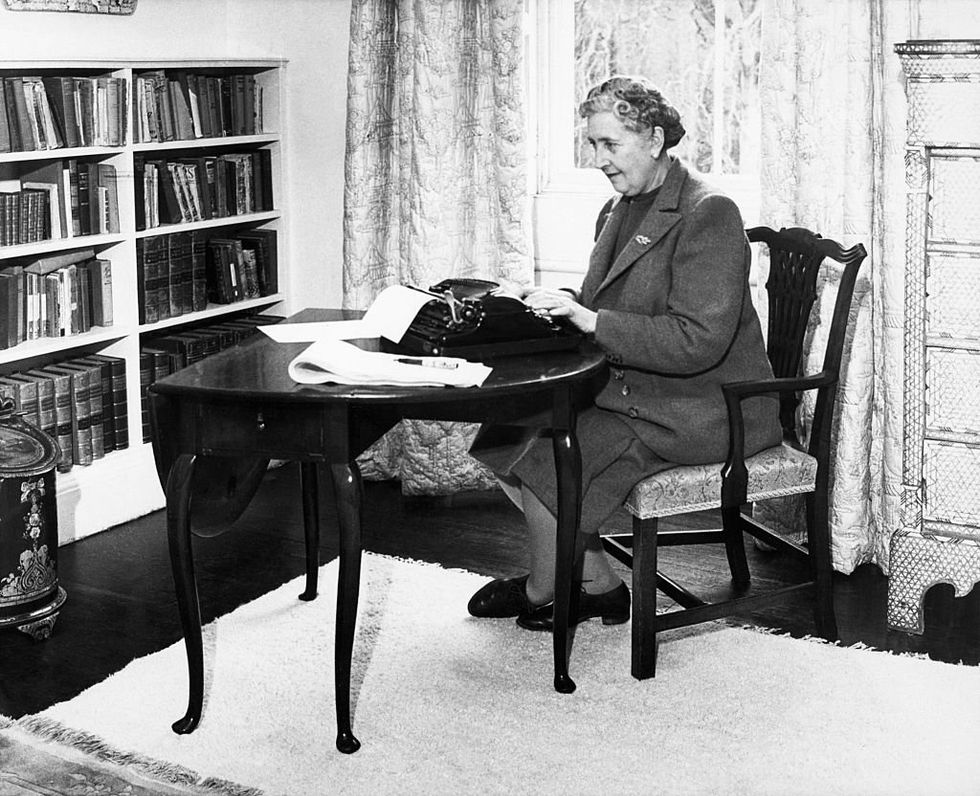

Joan Didion harbored a deep-rooted reserve of disgust at the aesthetics of sad middle-class boys and girls, so of course, her legacy has been turned into a mess of lifestyle porn and mangled quotes.

I said I needed to make money: I wanted the pleasure of broken bones, the satisfaction of labor.

I’ve been returning to the alleged scathing takedown of feminism, allegedly perpetrated by Joan Didion in her 1972 New York Times essay, “The Women’s Movement.” True, Didion found no value in the ideology – its core was hollow, borrowed from Marxism: she refused to acknowledge “the women” as an oppressed class on the grounds of gender alone, and, in a bit of crucial timing, she could point out the aspirational slide of the movement itself as the proof it had failed already, 1972 is a banner year for the soft-focus, New York City, get drinks in all the bookstores Type of Girl:

“More and more we have been hearing the wishful voices of just such perpetual adolescents, the voices of women scarred by resentment, not of their class position as women but at the failure of their childhood expectations and misapprehensions.”

Joan Didion harbored a deep-rooted reserve of disgust at the aesthetics of sad middle-class boys and girls, so of course, her legacy has been turned into a mess of lifestyle porn and mangled quotes. However, it’s not like the audience members who yearn for her sartorial choices will ever sit still and do the work for the decades it takes to build the body underneath the clothes. Let me think if that’s unfair.