NASA/Getty

A detour to a SpaceX launch leads to a discussion of the history of space travel and our role in the universe.

A few days after our recent interview, science writer Joe Pappalardo took his 89-year-old dad to the SpaceX Starbase in Boca Chica, Texas. Before he'd entered the facility, the elder Mr. Pappalardo had never seen anything like it. At the entrance, he examined the message inscribed on the giant outer wall: “GATEWAY TO MARS.”

These kinds of declarative (and imperative) statements rouse something prelinguistic in us. For some reason, humans have evolved into conquerors, desperate for more territory. This is good. It’s one of our finest qualities.

So father and son approached the hulking megastructures of Elon Musk’s aerospace wonderland, and Musk’s promises became more noticeable. Space flight, of course, but most impressively, the possibility of a safe return, rocket and all.

Sunlight poured down, and the world around Mr. Pappalardo must have felt mechanically different as he strolled into the bustling, futuristic cityscape. Jutting up from the swarm are three giant modules, 160 feet tall. Were these the spires and beams of a science amusement park?

It was all so advanced.

He hadn’t expected so much construction, but when he considered it, it made sense: Invention and trial demand constant upkeep. Like ants ferrying soil into an empire, the hubbub of activity became a spectacle of its own. He couldn’t believe how many people were there, and he wondered why so many of them had cameras.

“One guy out there had a telephoto zoom lens on his camera,” he tells me. “He was taking pictures of everything. Maybe you're thinking, ‘Maybe he was a spy.’ Never know.”

Mr. Pappalardo remembers waking everyone up to witness Neil Armstrong’s first steps on the lunar surface. The entire family was vacationing on the Jersey Shore. After a day at the beach, they were all tired, but that didn’t matter because there was a man, an American, on the moon with his giant space boots.

But the machinery of SpaceX is insurmountably more advanced.

At 5,000 tons, Starship is the largest, most powerful rocket ever made, about the height of the Pyramid of Giza. It’s designed to be reusable. Starbase has 10 Starship launches, four of which also returned a landing.

“The launch pad has these appendages called ‘chopsticks,’” Mr. Pappalardo tells me, “where they plan on having the rocket come back and land on the launch pad where it left, which is quite remarkable.”

As you can tell by his quotes, the man is incredibly sharp, not for his age, but in general. We spoke for 30 minutes, late afternoon, and he could have kept chatting for an hour.

Born and raised in Haverstraw, New York, Mr. Pappalardo was a chemist for decades. His demeanor and intellectual precision reflect this, though not in the form of austerity.

I ask, “Do the principles of the laboratory emerge in the Starbase setting?”

“Well, it is very different,” he says, “ because in the laboratory, we're dealing with little things, but the principles are the same. When you want to achieve something, you develop a hypothesis of how you want to get there, and you test it and get there.”

In his Northeastern baritone, Mr. Pappalardo recalls his sailing days. One trip took him from Antigua in the Caribbean to Charleston, South Carolina. He quickly learned the difference between sailing on the sea straight through the Bermuda Triangle and navigating the beastly power of the Atlantic Ocean.

When storms hit, the waves could become mountainous.

“You can see waves higher over your head on your left and waves over your head on your right,” he tells me. “Now, you know the physics of it, that the waves can't do this,” he brings his hands together, “they can't combine, but while you're there you're not too sure.”

Sometimes, the endless waves stung with loneliness — the howl of repetition full of clouds. But perhaps most of all, he remembers the moments of tranquility.

“At nighttime when you hold the wheel and the boat is just hissing along through the surf and nothing around, it's all dark and just the moon: It's beautiful, absolutely beautiful.”

Remember: Humans used to know a world of clear water, and what we did was build a ship and explore.

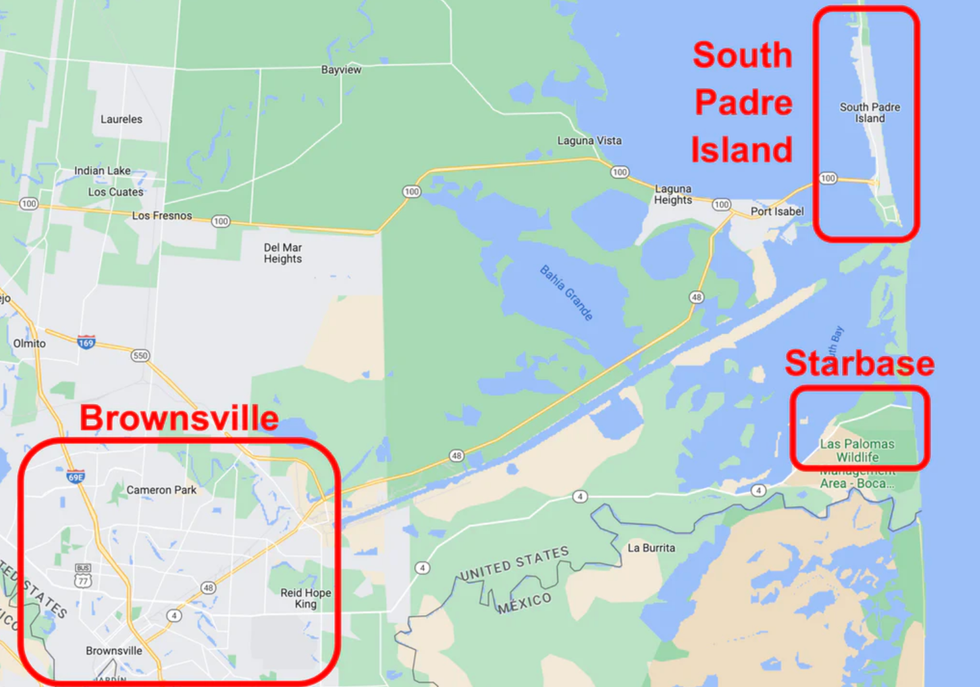

Head east a smidge along the Gulf of Mexico, and you’ll run into South Padre Island, where enthusiastic college kids have been known to chug until they start puking.

Brownsville, in the other direction, has repeatedly been a battleground of all sorts over the past two centuries. It is one of America’s southernmost points — you can practically sneeze at Mexico and make contact.

The closeness of it all feels uncanny, yet American, as if these locations had spilled out by accident and suctioned together like a Ziploc full of random souvenirs that don’t belong.

Of course, what’s more American than this uncanny accidental mishmash of events, ideas, and places, where a person like Mr. Pappalardo can begin life as the son of Italian immigrants and then quickly, invisibly plug into the depths of a history like ours, so vibrant and strong and broken?

We discuss the engulfing pace of change, the fever of acceleration that keeps outpacing everything, even itself, too powerful and inhuman to get tired. These breakthroughs leap to action daily.

“The problem is that they're advancing so fast that no one can possibly keep up,” he tells me. “But every time this subject comes up, I always think of my father. He went from the horse-and-buggy days to the man on the moon. You don't get any more variation than that.”

The debate is between the evangelists of a neuro-connective frontier, where technology, as an instrument, builds and destroys only at someone’s command, and the rapture-loving snobs all too eager to convince greater society to be sad about capitalism in a whole new depressing way.

In his spaz of a book “One-Dimensional Man,” Frankfurt School mainstay Herbert Marcuse characterizes technology as “an instrument for control and domination” and mass media as an integral part of that process. (Well, at least he’s right about the dubious habits of the media apparatus.)

Marcuse frames this as the technological domination of our “advanced industrial society” and thus devotes himself to rattling the “new forms of control” that arise as part of this “one-dimensional society.”

It strikes me as a paranoid and stubbornly theoretical stance, itself one-dimensional. There’s an incoherence to this lot’s obsession with characterizing technology as totalitarian. Instead, we have a society shaped by technological monks and bureaucrats who, yes, have special access to mass events. But this is entirely different from owning an iPhone.

Tech is precisely what diminishes and even capsizes any sort of political rapture. It does appear that technology has eradicated geography as a reality or obstacle. But in its place, we have limitless access to the code of human thought.

Like every other anecdote Mr. Pappalardo provides, this is guided by a spirit of exploration.

As Italian philosopher Bifo Berardi observes in his book "Futurability," “Technology is not a chain of logical implications, but a field of immanent conflicting possibilities.” These potentialities strengthen the connective force of digital neural networks.

In a world that constantly grows closer to all of its network machinery, including us, and all the equipment we have transformed into accidents and failures, with the one periodic success among them — the ship still belongs to both the expedition and the shipwreck.

Because method, questions, and curiosity can calm the rigors of progress.