Graphics by Alexander Somoskey, Photo by Kevin Ryan

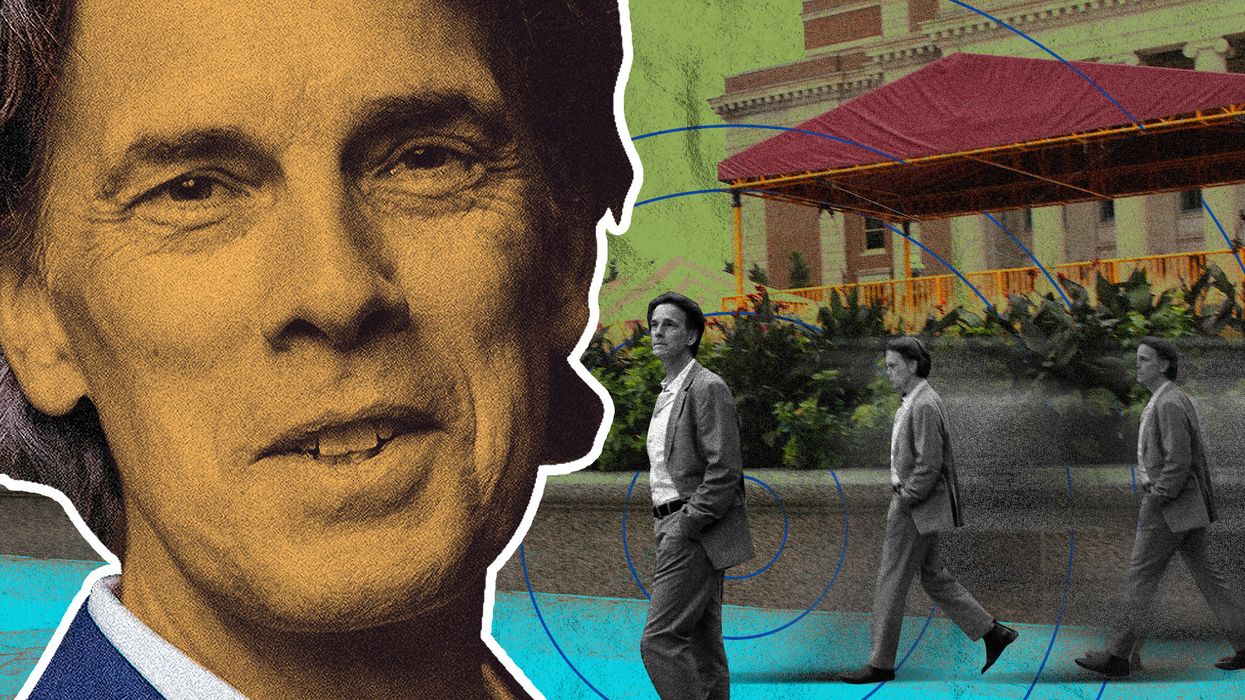

Enter into the philosopher's cave with Stephen Hicks, the philosopher influencing the influencers

I took a trip offshore. Took the whip offshore. — Rae Sremmurd

The philosopher navigates from the passenger seat of our Mazda CX-3 as we cross Stone Arch Bridge in deepening afternoon, over the North Mississippi with its polluted blue water.

"Everything is connected," he says. "Everything has implications."

When he talks, he floats his hands. Throughout the day, random objects will fumble toward him: a pen, a button, a coaster. Each time, he will snatch them before anything falls.

"I think language first should be cognitive, connecting your mind to reality," he says. "What are you trying to communicate? How are you trying to connect with people?"

His work has been published in 16 languages, on every inhabitable continent. He's the influence behind the influence. His ideas guide some the most renowned (and often most controversial) thinkers of our time. Jordan Peterson has heartily endorsed the philosopher's most well-known book, and has even been known to hoist it into the air while saying "you need to read this! I'm not kidding!"

The philosopher travels all over the world giving lectures, and has served as an honorary professor at multiple universities, including Georgetown and Oxford. Recently, during a stint at the University of Kasimir the Great in Poland, he toured Auschwitz and Treblinka Concentrations camps. It was January, and the air at Treblinka was frigid.

"Auschwitz, the older part, was worse," he says, "with its torture chambers and execution wall and evil-looking gas chamber." He tried to imagine how prisoners survived in that relentless cold. "Overwhelming to be where humans did such brutal acts upon other human beings."

Last week, at the annual Atlas Society Gala in New York City, he donned a tuxedo and gave a speech about superheroes and said that young people are full of undiscovered good. Today, he spoke at a regional conference held by Students for Liberty (SFL), an international nonprofit for students devoted to libertarian and classical liberal values.

"You could say there are two types of people," he says. "There are those who are true believers in whatever narrow set of readings and ideology that they've been exposed to, and they just want to be activists — but there is a lot of nihilism in these sub-circles as well, and they're deeply resentful, and it's not just a political resentment, it seems to be a resentment against reality."

He adds that Jean-Jacques Rousseau's socialist ideology led to the French Revolution, and isn't it incredible yet terrifying that ideas can provoke a revolution to begin with?

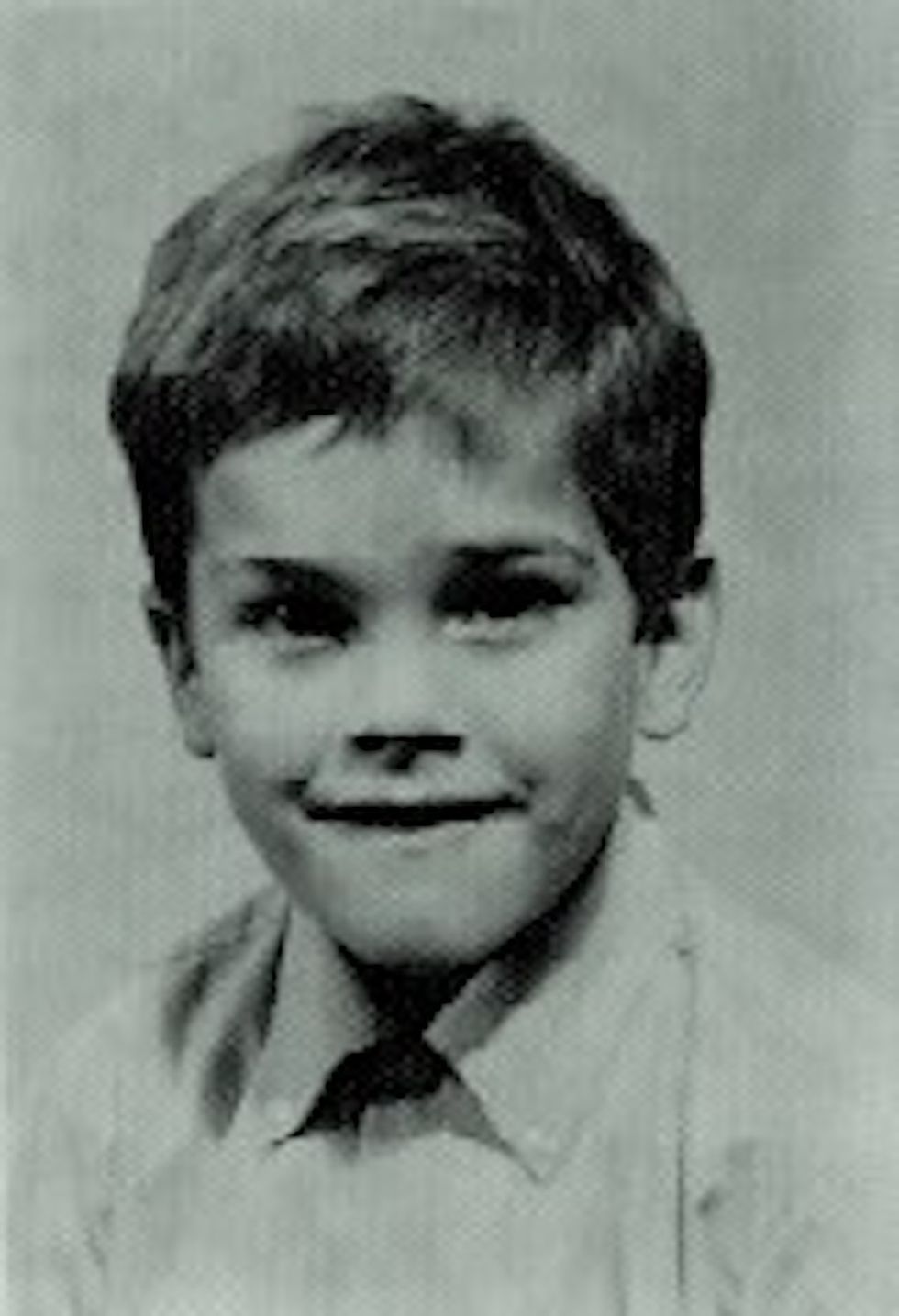

Then he wanders back to the subject of post-World War II philosophy before he can describe the second type of person, but, as the months unfold in my reporting, as this story drifts along, the second type of person will emerge. Wide-eyed, the philosopher keeps the posture of a well-mannered child at a piano lesson. Clean-shaven, smooth-featured, 6-or-so feet tall, 58 years young, distinguishably thin— a safe 15 pounds from the scrawniness of a young David Byrne — with a black woolen sweater tied in a Parisian knot around his shoulders, he talks at a steady pace, not rushing but not wasting time. He trenches so deeply into descriptions of Existentialism that he keeps forgetting to look at the GPS on his phone, and we veer off in every direction.

Philosopher Stephen Hicks thrives on information. Art, economics, religion, humor, language. One conversation, he talks about trade unions. Next, the Lake District Poets and their sad, still music of humanity. Next, the four forces of physics. Next, predictions about geopolitical relations, concerning-but-not-limited-to:

In a phone interview, Khalil Habib, associate professor of Philosophy at Salve Regina University in Newport, Rhode Island, described Hicks' ability to make connections: "It's always, 'Here's a great figure, and here's why they matter, and how they have mattered in our lives.'"

During a lecture on Marxism, Hicks might allude to Samuel Beckett's "Waiting for Godot," a strange play about two men at a crossroads. Maybe he'll use a quotation from Apple founder Steve Jobs to explain the notoriously convoluted arguments of German philosopher Immanuel Kant. Hicks' website is a veritable treasure trove of ideas. Video lectures, guided notes, audiobooks, translations, book reviews, PowerPoints, and, most recently, his podcast series, "Open College with Dr. Stephen Hicks." He even provides materials from the courses he's taught, an entire PhD worth of philosophy. There are links to the documents, poems, short stories, essays, and articles that he deems valuable — all the primary sources — and a page with quotations about the meaning of life, compiled with the everyman spirit that defines Hicks overall. Lines from "Dust in the Wind" by Kansas next to a passage from Psalms and excerpts from a speech by author John Steinbeck, comedian Robin Williams and "Macbeth" and philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, all in the one place.

But Hicks is best known for his book "Explaining Postmodernism: Skepticism and Socialism from Rousseau to Foucault," which has become a handbook for critiquing early postmodernism — the vast, web-like political and cultural movement that emerged from 1960s French literary theory, guided by rebellion, by protest and skepticism and a rejection of institutions and a distrust for the status quo and the world of tradition. Postmodernism is driven by the notion that objective truth does not exist, or at least not the way it used to.

For Hicks, truth does exist. Reason does exist.

In "Explaining Postmodernism" he argues that our understanding of shared life — technology, economics, science, politics, language, art, taste — is shaped by philosophy, so the dominant philosophy, in Hicks' view postmodernism, has the potential to harm society. As he sees it: skepticism, nihilism, relativism. He believes that you can replace bad ideas with good ideas, and that as a result human life as a whole will improve.

In an email, Eduardo Marty, founder and executive director of the Argentina branch of Junior Achievement, described Hicks as "one of the few able to discover intellectual mistakes that laid deep down at the bottom of our culture." Hicks is optimistic about the future of humankind, our collective potential to face reality, to maintain faith in one another, to find beauty and create art. He counters what he sees as the nullity of postmodernism by tracing the history of philosophy.

"The problem with politicization is that drawing out those political implications much too quickly, and not being aware that there are other forks in the roads and other alternatives that one can pursue," Hicks says. "And then also the other problem is starting with the politics, and just using the philosophy and everything else as a cover story or a rationalization for political conclusions that you want to get to anyways — that's probably the bigger sin."

In an email, Kevin Hill, associate professor of Philosophy at Portland State University, described Hicks as a defender of the idea that philosophy actually matters: "That the ideas of the great philosophers, for better or worse, eventually have enormous effects on all aspects of life." Eduardo Marty added that "civilization and modern life have more chances of survival after Stephen's book." The adage goes something like, "academia is upstream of culture, and culture is upstream of politics," i.e. theory leads action that leads to policy which inspires new theory, ad nauseam.

Many of the reviews of "Explaining Postmodernism" are as steeped in academic jargon as you might imagine. But one reviewer said it well:

"This is not a purely historical work. It is also a critique, and in many places it is vigorously polemical. Hicks makes a commendable effort to provide a balanced account of the philosophers he discusses, but his emphasis is clearly on aspects of their thought of greatest relevance to the development of postmodernism. In any case, it takes courage for a philosopher at an American university to say some of the things Hicks says in this book.

"Explaining Postmodernism" is read more outside than inside academia, so, as a friend of Hicks put it, Hicks "has made a cultural impact far beyond the impact that most academic philosophers ever have," largely because academic philosophers tend to talk to each other exclusively.

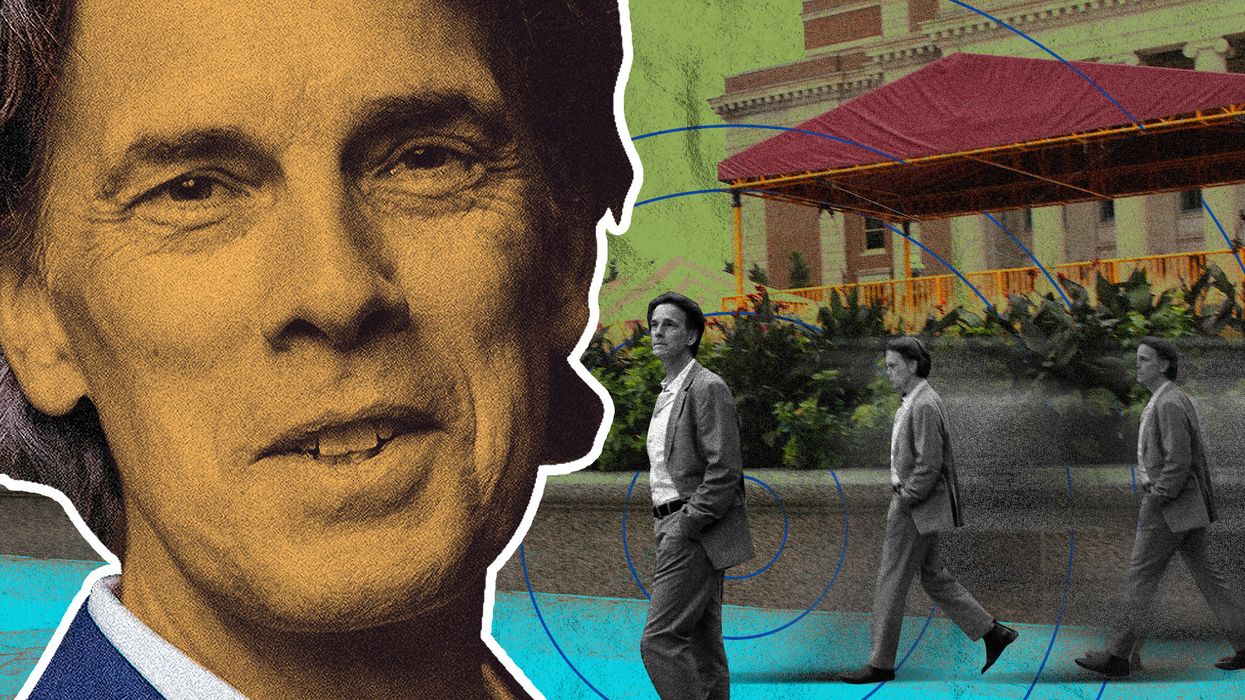

Meaning, Hicks resides in the weird territory between academia and the mainstream. But it's a natural harmony for him. All his life, he's hovered between the world of ideas and the world of grit and ordinary commotion. His mother was pregnant at 17. She and Hicks's dad were just out of high school. Occasionally, they had to raid the couch for loose coins.

Hicks grew up surrounded by books: his mom more interested in literature, his dad more of a "hard-headed entrepreneurial businessman." In his late teens, Hicks worked at an iron foundry in Ontario. Glass furnaces. Eddying, torrid waterfalls of orange-gray muck. He admired the way liquid iron — boiling and deadly — can be molded, re-shaped into whatever you want.

At night, at home, he read everything he could.

Then came the oil boom in Western Canada, when there was a need for, in his words, "ignorant kids who would get paid well for dangerous labor." He made good money roughnecking. Bought a motorcycle. Then he traveled around Europe and North Africa. When he describes Morocco and its narrow market lanes and calibrated ruins and wavering sand, a calm wideness overtakes his pupils.

While taking night classes, Hicks spent two years at construction companies around Ontario, Quebec, and Saskatchewan. He loved carpentry. He found concrete fascinating. Felt like a kid in a sandbox, sculpting formless mud into something permanent, something solid, something that makes highways and sidewalks and roads.

"The postmoderns are smart," Hicks says, on his second coffee. "They're connected, they're organized. They have the awesome financial resources that can be marshaled in the U.S. and Canada at their disposal. They're loud, there's lots of them, and they are in positions of cultural importance, in a lot of the institutions that they are dominating."

Obstacle one: postmodernism is head-spinningly dense and elusive. In its three generations, it has evolved into a multitude of differing, often-contradictory forms, making it nearly impossible to define. Many on the left and in academia insist that postmodernism is dead and that there is no such thing as a postmodernist anymore, only a boogeyman fabricated by conservatives who have a grudge against academia, which they consider leftist, rooted in hostile attribution bias.

Others claim that, while postmodernism is dead within academia, it survives in practice via activism, politics, and art. (Or vice versa: that it still holds sway among the professoriate, but practical postmodernism is nonexistent.) Others still claim that postmodernism has sewn itself into every aspect of life, has become so powerful that we can't even see it anymore, despite its being everywhere. According to the tenets of postmodernism, all the above assertions are correct. But also not.

Jean-Francois Lyotard, the first official postmodernist, defined "postmodernism" as "incredulity towards meta-narratives," i.e. the explanation behind any system, theory, belief, or movement that claims to have a solution or answer for everything. Freudianism, religion, capitalism, Marxism. Even Philosophy ... including postmodernism, i.e., it denounces itself in its own definition. But is that any stranger or more chaotic than everyday life has become? When's the last time you looked at the world and thought, "all of this makes perfect sense"? We live in a postmodern world. For postmodern reasons. As humans, we've reached a level of awareness that constantly topples us. This is partly what early postmodern philosopher Michel Foucault meant when he described man as "a recent invention."

Hicks rejects any such allure. He sees postmodernism as a purely negative force.

"If you're a skeptic, then all you're left with is various kinds of subjective values," he says, "[so that] nobody can ground their values. Language itself becomes a tool, which they need for confrontation. They use it as a weapon. And anyone who is an enemy — an ideological enemy or a political enemy — you want weapons that will put people on the defensive."

This idea, that postmodernists will say anything (e.g. "postmodernism doesn't exist, it's a right-wing conspiracy theory"), hurls us into the ultimate liar's paradox: who do we trust? It's "Alice in Wonderland" played out every day using shade and conjecture. The solution, according to Hicks, is "a lot of good, healthy activism of the right sort."

Over the past few decades, there has been plenty of this activism, as various scholars have protested and confronted postmodernism using the academic equivalent of a Sacha Baron Cohen prank. In 1996, physics professor Alan Sokal successfully Trojan-horsed into a peer-reviewed postmodern journal with an article claiming that gravity is a social construct.

More recently: the "Grievance Studies affair" — scholars Peter Boghossian, James Lindsay, and Helen Pluckrose targeted academic journals in the fields of gender studies, queer studies, fat studies, and something called "feminist geography." Their articles examine female penises, "fat bodybuilding," "breastraunt masculinity," and canine rape culture/"queer performativity" among dogs. Elsewhere, they argued that the solution to "trans-hysteria" is the sexual act of pegging. In another, titled, "Our Struggle is My Struggle," they translated passages of Hitler's "Mein Kampf" into postmodern feminist lingo.

Like Hicks, like so many other postmodern critics, they use versions of the word "liberal" to describe themselves, and, while far from conservative, they have found the center-left, center, center-right, and right to be oddly welcoming as of late, and the far-left and far-right to be ugly and loud.

"Liberals are suddenly feeling the need to distinguish themselves from progressives," Hicks says. "Because progressives are one step closer to a sort of authoritarianism. But the progressives are saying, 'no no no, we need to distinguish ourselves from the postmodernists. Because if we're progressives on the left we actually believe in equality and justice and these are real values and government authorities should do good work.' So they're still arguing on realist grounds for that chunk of the political spectrum. Whereas the postmoderns are saying, 'everything is crap, there is no truth, there is no justice."

When I spoke with Boghossian and Lindsay, they both eagerly noted that Helen Pluckrose's work complements Hicks' to give a full diagram of postmodernism. Hicks' "Explaining Postmodernism" examines the philosophy's predecessors and its early days, then hands it off to Pluckrose, who traces postmodernism through the '80s and '90s, as it splintered and grew.

In an email, Pluckrose spoke fondly of Hicks: "I think he connects the politics to Marxism a bit too neatly but even there, he is nuanced and acknowledges that postmodernism replaced Marxism for many and isn't really a continuation of it." She added that the point of postmodernism is to take things apart, not build them. "It will destroy itself at some point," she wrote, "but it can do much damage to society before that happens."

Hicks considers postmodernism the major intellectual threat of our time.

"At the same I step back sometimes and say, the enemies that we're facing right now are relatively small and shabby, by historical comparison," he adds. "It's not like we are in the 1930s, going through a Depression, and it's not like we're in the 1940s and we're actually fighting the Nazis and the Japanese and their huge war machines. It's not like we're actually in the Cold War, where there's nuclear weapons pointed at us."

Hicks' critics are almost uniformly — and vocally — left-leaning, and tend to be the same people who criticize psychology professor and author Jordan Peterson. They seem to hate that he aligns with Objectivism, the capitalist philosophy created by Ayn Rand. (Interestingly, Hicks said in an email that Rand receives criticism from both the far-left and the far-right.)

For the most part, his fellow academics have praised his work, at times exuberantly. But, as has become the norm, social media reactions have less nuance. A sign of the times that the most vociferous responses to Hicks' work appear online, in bombastic posts by armchair philosophers — anonymous, of course — whose qualifications ("I minored in philosophy" or "I have two bookshelves for books by and about Kant alone") are as shabby as their invective is pompous. They weirdly match Hicks' definition of modern-day postmodernists better than anyone else.

Mostly, though, people have positive things to say. Call it the Jordan Peterson effect. Either praise or venom, no in-between. All bad or all good. Interpretation, in other words. Because how can something be true and untrue at the same time? How can the same passages of the book be considered false by one group yet faultless by another?

"The facts of reality exist," Hicks says. "But truth — the cognitive grasp of the facts — takes effort."

For Hicks, this is a human effort, and it encompasses everything. For example, earlier, on this mid-October Saturday, at the Hilton on Marquette Avenue in Minneapolis, Hicks cramped into a bony-necked chair at a high-top smushed against the wall, 20 feet from a breakfast buffet, and pricked at a mound of eggs and toast and sausage as he spoke about the nasty critics of singer-songwriter Bob Seger.

"I think there should be a benevolence: 'Look at this wonderful thing that we share.' But then for some people, in the social one-upmanship, pecking order becomes more important to them than the foundational love of music that they all share," he said. Hicks, always on the prowl for meaning, is even able to philosophize about the man who sings "Like a Rock" in the Chevy commercials.

Since 9 a.m., attendees of the Students for Liberty conference have occupied the second floor of Tate Hall, a sleek medical building full of eye-wash stations and laboratories. As soon as Hicks arrives at the card-table check-in that is covered with name tags, a young woman in a prim beige dress and a young man in a box-like suit wave and smile deferentially and shake Hicks' hand and say "thank you, thank you so much for coming, thank you," then lead him down a weave of yellowish stairs and out a backdoor, giving him the rundown as they pace to the broad stairway of an adjacent building, where a hundred-odd students are posed for a group photo.

Back inside, students flood into a classroom that serves as the conference hub. Oblong tables crowd with books and supplemental reading and pamphlets of every size and quality, including none other than the Constitution of the United States of America. There are rows of booths. Republican Liberty Caucus, with yards signs that say "Vote Republican" in aggressive red. Minnesota Campaign for Full Legalization (weed). Ladies of Liberty Alliance. Atlas Society. And lots of Libertarians, some of whom happen to be the only people in attendance you could call shaggy.

The room designated for Hicks' talk is clearly meant for chemistry classes: All the chairs face a long smooth table with sinks and microscopes and notecards smeared with pudgy, handwritten formulas. Hicks chats with the conference organizer/Regional Director Charlie Gers, who ran as the sole Libertarian candidate in the 2017 Minneapolis mayoral election. He lost, but he's still barely 23 years old. And he has the calm disposition of someone twice his age. He'll be fine! Then "The Moral Case for Liberal Capitalism" appears on two giant screens at each side of the comically long whiteboard and Hicks begins. Never has a group of students been as penitent and respectful! Like 45 minutes of church, it felt like. And all looking sharp in their suits and dresses.

The entire scene complicates the ongoing debate about the state of academia. For people on the right, this gathering of politically-diverse young people proves the "silent majority" narrative, a confirmation that anti-conservative bias in academia is real, so real that conservative students feel the need to gather in safety. For people on the left, it could serve as a counterargument to the conservative narrative that leftist operatives masquerading as professors have seized higher education in order to indoctrinate young people, organizing into a cult-like social force with a radically leftist purview. Sure, the data indicate that professors have gotten far more liberal. But nobody can agree on what this means exactly. Either way, the civility of today's conference — no protesters, no yelling, no tantrums, no petitions — feels encouraging. Suppose it's a sign that the bickering is almost over, that divisiveness is on the wane, that hatred is losing power, that politics is receding, that life as we knew it might even resume.

After the speech, a crowd gathers around Hicks, and one student head-down shoves his way to the front like a linebacker.

"I'm a socialist," he says, then hoists a few accusations at Hicks, who hardly blinks as the student twitches his words. Then Hicks tells the student that he learned about socialism by studying economics, history, philosophy, ethics, but do you know how most socialists learn about socialism? Yes, through romantic notions, cinematic fantasies, maybe a flighty biography of Che, and meanwhile wouldn't they be the first to starve?

The student wants to argue against loyalties to truth. Hicks is having none of it. He challenges the student for contradicting himself, then, leaning down a bit, says, "See, now that's the third time you've backtracked and completely reneged and, I have to wonder, what exactly do you stand for?"

Kevin Hill described Hicks's public demeanor as reminiscent of Mister Spock, from "Star Trek." Not that he is "suppressing his emotions in some stoical sense, but in his unflappableness, his reasonableness, and a wry, amused sense of irony," and that he "is fired by a tremendous moral passion." In my reporting, I encountered metaphors like these a lot. Khalil Habib admires "the way that Stephen reasons with you like a calm parent, explaining to you why putting your finger in the light socket is just not really in your best interest. And he just walks you through very soberly those ideas."

Back in the car, facing the blue-grooved silhouette of Minneapolis, I ask Hicks about the socialist student. Hicks says he tends to give students the benefit of the doubt.

"When you're 18-to-22, in many cases you've had a partial education, and that's fine, but you should be trying out all these ideas and almost any political ideology can be given a nice initial spin. If you're open-minded and that's the first one you hear, then it makes sense that you'd be attracted to it and you'd want to explore it further, then you start looking at the world from that lens. That's also what a university education should be doing, is putting you in contact with people who have other ideologies, so you have to do the compare-and-contrast, and if you're a professor that's what you live for."

He reclines in thought, in his purple-chalk dress shirt and tailored suit but no tie and his black leather boots that zip up at the sides and his Danjue Leather satchel.

"I think he'll be fine. It didn't strike me that he was attracted to socialism for the wrong reasons, it's not like he wanted to be a Stalinist, he just hasn't thought it through," Hicks says.

Then he talks about the importance of meaning. He finds meaning in everything. Even the most seemingly mundane events.

"Everything is connected," he says, as we cross Stone Arch Bridge. "Everything has implications."

He points out at the open sky, hatched in grey. What does that mean? Precipitation, of course, but what does it mean on a deeper level? This morning, the weather was biting and quick like Spring. Then, it got warmer, and now it falls into evening. Tomorrow, snow will blanket the entire city, the entire upper hulk of North America. Yet, the snow won't be winter-like or deathly or confining. It will not signify an end. The same thing will happen when Hicks and I meet a month later, and he'll smile a little crosswise and say, "Again? It must be a sign."

Slumped in gaudy chairs in the hotel lobby, we wait around, 30 minutes until the SFL social. Hicks has been philosophizing for 10 hours now. Dark light murmurs through the din of people talking. Marble floors bounce each consonant farther. The clatter of plates, the plink of glasses, the 80-decibel blare of "Mirrors" by Justin Timberlake. It's an odd setting for a philosopher's session, especially now, as the philosopher is hitting stride, finally cornering the argument he has built all day.

"A certain amount of what has allowed postmodernism to spread as much as it has must to be chalked up to a sort of low-grade cowardice," he says. "You don't want to have to confront people in faculty meetings? or take a stand? Well — especially if you're a tenured professor — what have you got to be afraid of?

"My goodness!

"So we now have a generation of intellectuals who are third- or fourth-generation postmodern, and they're anti-intellectual. Anything that's too difficult for them, they haven't engaged with it, they don't really understand it, and, of course, in addition to their anti-intellectualism, they have a brutalist psychology. Anything that holds out any possibility for positivity in the world, or in the next world, just does not speak to them. For them, the goal is a matter of shutting down an alien psychological and intellectual framework. It's an intellectual and a political territory that they've staked out for themselves, and they know how to check the right boxes, but really they are activists."

He pauses. "Confronting power is also an important theme of the Western tradition. Reflecting on power, reflecting on authority, and the whole idea that questioning authority and jealously guarding prerogatives or rightness — that whatever power is in play, it ultimately needs to be grounded in a respect for human individuality, human dignity. So speaking truth to power, challenging authority, being willing to revolt, rise up radically against authority when it's wrong — I'm entirely in favor of all of that. But they have to be in the service of truth, in the service of justice, goodness, and so forth. So that then is to say, if you think there are such things as universal principles that are true and just, that you then have every right to challenge those who are in positions of power.

"But, with the postmodernists, you end up with a naked power struggle which comes out in the most ugly form in the victim movement as 'The powers that be have abused us, and victimized us,' and sometimes there are large grains of truth in those claims. But when you convert victimization into your primary trump card, and you think that gives you the moral right to do anything that you want in response, then it becomes transparent. Because you over-exaggerate your victimization, and the purpose of that is to give a pretend justification for the kinds of power plays that you're going to engage in. I think the game becomes transparent when the previously self-identified victims then get into positions of power and become terribly authoritarian and politically correct in the worst ways, which always indicates that a commitment to protecting the vulnerable and the weak is not really what's driving them.

"This is why I think Jonathan Haidt, Steven Pinker, Jordan Peterson and others, and if I can include myself in that company — we're all on the same side. And the issue is being an enlightenment liberal against a postmodern authoritarian. And the 'enlightenment' part is a bottom-line respect for reality, and reason, and both of those are being jettisoned by the postmoderns, who are anti-realistic, anti-reason. And then the 'liberal' is in that broad, classically-liberal sense. So that while Haidt would describe himself as an American liberal; Pinker puts himself more on the liberal left; Jordan Peterson, I think he's understandably cagey about a lot of his political views, but he strikes me as a little more culturally conservative; and then I'm more libertarian.

"But all of those political differences are just an internal argument in a classically-liberal individualistic framework that we all have. And all that's against what is very clearly an authoritarian, 'take-it-to-the-streets', 'punch-people-in-the-face' left."

Breeze drifts past a runaway sky. The last scud of day. The pale, tepid final winnows of day.

In the car, as we glide toward the SFL social, Hicks talks about Albert Camus, the moody French philosopher who was obsessed with death and suicide but who came around, then died in a car accident at 46. With a gasp, I flinch, then splinter the wheel to the left to avoid an animal carcass in the road, unalterably red and barely larger than a squirrel. Then, we turn, and a vibrant clutch of oak trees sharpens together like a chapel — call it a heartening coincidence — then opens into the sprawling, ornate campus of the University of Minnesota.

I say it's like a prayer and quote a poem:

you can't beat death but

you can beat death in life, sometimes.

and the more often you learn to do it,

the more light there will be.

The downstairs portion of Burrito Loco is humid and pitiful. Rankled and useless and lacking in customers, of activity of any kind. Half bar, half Mexican restaurant. Cheap beer on tap. Upstairs — that's where the life is! Most of the SFL conference attendees and staff are there. And as soon as Hicks rounds the stairhead, everyone bobbles their heads toward him and grins. Most people grip some weird pink vodka cocktail — which it turns out is the only complimentary drink available to SFL attendees. Upside is, unlimited refills. Many of the students bobble around with a silly ruddiness, shouting conversationally as they bumper-car from discussions about Austrian economics to plates of fried cheese, then back to the bar for more of that pink stuff.

Hicks is immediately stopped by a 23-year-old-ish guy with his tie loosened. He brought "Explaining Postmodernism" and would Hicks mind signing it? As Hicks glides the pen along the blank page, the student chatters and chatters, like a kid describing their favorite movie, only he's talking about Objectivism or something or other. He says, "Dr. Hicks, you are going to change the world," then asks "What endless problems do we face as a culture?"

"There are two regularities in human experience that strike me," Hicks answers. "Every generation has those who don't think much and so who fall into the same easy mistakes of previous generations. And every generation has those who think much and find clever ways to talk themselves into denying easy truths."

The student leans into Hicks and shouts over featureless music.

"Yes, yes," Hicks replies. "It's a faith-in-humanity kind of thing. You young people, when you come along, you want to live a real life. You are not yet corrupted. And you are out there, always."

An hour later, we taper down the planking stairs, through the old world doorway into the cold. The sky lingers in that oversized way when every color has a toe in the pond, full of God's creations. Icy and brittle, the air weighs more than it did earlier, smelling neutral like used dryer sheets.