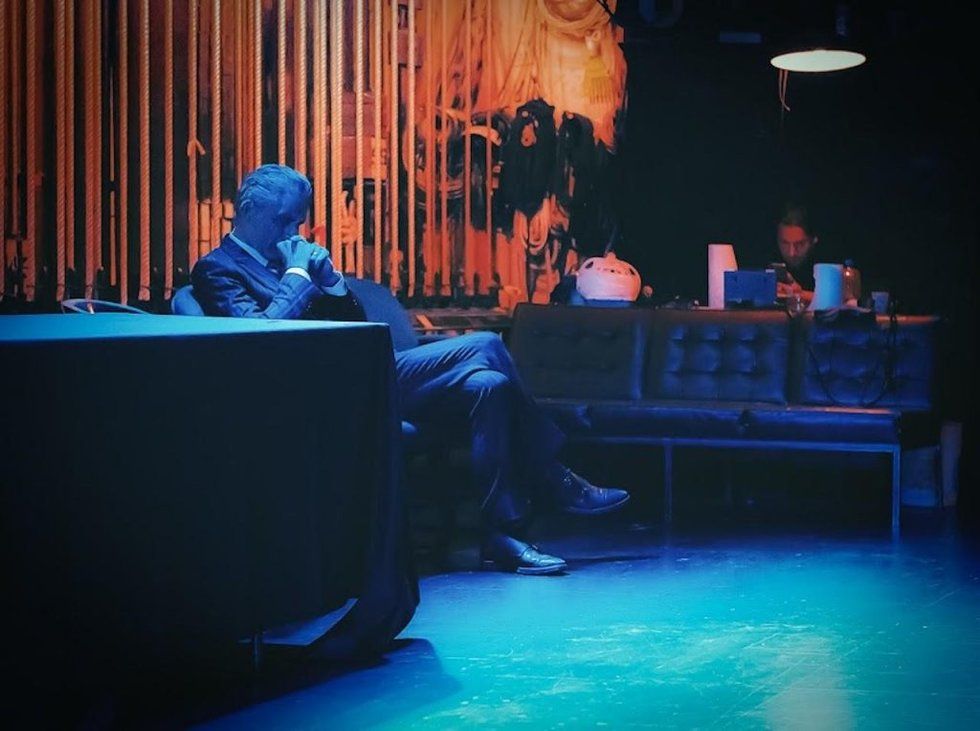

Jordan Peterson prepares to talk to his audience on his book tour. (Image Source: Kevin Ryan)

"I'm living in the 21st century, doing something mean to it" — Kanye West

People around here believe in Jesus. They believe that when it rains, spiders and cockroaches rush into your house for shelter. In this scenario, Jordan Peterson is Jesus, but he's also the spiders that embed in your walls. He's messianic and vile at the same time. Equal parts love and hate.

For those who haven't heard of him, know that Peterson is a sort of cultural Rorschach Test. People love him and hate him with equal measures of hysteria, depending on what they see. He's a big deal. Many consider him the voice of a generation. He is, but in the same way that Trump or Drake or Lena Dunham is. And since January, he has been touring the U.S. and Canada with Dave Rubin for the "12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos" book tour. Today, Tuesday, May 29, 2018, it's at the Revention Music Center, a Wal-Mart-sized venue tucked into Houston's Theater District. The show is sold out. Doors open in an hour. Onstage, a man tests the microphone, “ch-ch-ch-ch-check two." From a mantle of shadow, Jordan Peterson appears, then paces down the red aisle, fiddling his fingers like Mr. Burns.

He's dressed in a sharp cajolement of blue — suit, socks, tie — with tinges of other colors that become secondary to blue. Gel determines the curvature of his silver hair. Strolling with a levered ease, he frowns. He's frowning as he shakes my hand. Rubin mentions the profile I wrote earlier this year. Peterson bobs his head with a gearshift nod. Turning to Rubin, “So he wrote your profile," Peterson asks. “And he did an honest job, you say? An honest profile? Really? Ah. No tricks, eh? He's probably just setting you up for a major trick."

He says it with the same dramatic tenor he uses when talking about chaos, darkness, dragons and hell. Sequestered boredom lingers behind his stare. Half playful, half aggressive. Most likely, he's sick of journalists. Well, that's a pretty bad way to start a conversation. Peterson strolls onto the bare stage, looking out at the expanse of seats. With a nod, “Now this is a different sort of theater."

Just as quickly, he strolls back up the red aisle then out through the black doors, a whir of a person. “Jordan likes to get out there and meet people," Rubin says, “before the shows and again after."

Rubin introduces me to John O'Connell, the tour manager, who is calm and immediately likable, soft-voiced in jeans and New Balance sneakers and a navy-blue blazer burnished at the elbows. He shuffles through a deck of press passes, each emblazoned with Jordan Peterson's face in purple light like a Jesus candle. O'Connell asks if this is the first time I've been to one of these shows. It is. “You're in for something magical," he says. “I've been doing this for decades, worked with a lot of musicians and a lot of speakers, I've worked a lot of shows. And only two people have ever gotten a response like the one I've seen from these crowds: Jordan, and Henry Rollins" (front-man of the 1980s hardcore-punk band Black Flag).

He pauses to let the unexpectedness breathe. “They're more similar than you think, Jordan and Rollins, they're speaking to people with this intensity, this passion, that they want people to help themselves and become better."

I first met Peterson and his wife Tammy in January at Rubin's studio. Tammy and I chatted as we watched The Rubin Report live-feed. She told me that Peterson really is the person that his fans imagine. More often, she said, he's too nice. She mentioned that Peterson has always been magnetic and deep and energized, even as a young boy. In elementary school, he would finish the entire year's schoolwork in the first few days. Tammy was present for the strange and volatile Cathy Newman interview. She said that Newman was friendly before the show, concerned with her hair and her dress.

Peterson's obvious nemesis is the media. Read a few profiles on Peterson and you'll quickly realize that most journalists feel the same way about him. Back and forth, back and forth. At times it feels like the cartoonish, hype-driven lead-up to a boxing title fight, with insults at weigh-ins and trash talk on ESPN. Take his spat with a critic who, in a review of "12 Rules for Life," called Peterson “a disturbing symptom of the malaise to which he promises a cure," describing his “brand of intellectual populism" as boosted by “predominantly male and frenzied followers, who seem ever-ready to pummel his critics on social media."

In response, Peterson took to social media and did the pummeling himself, calling the critic an “arrogant, racist son of a bitch" and a “sanctimonious prick." He wrote: “If you were in my room at the moment, I'd slap you happily."

Outside, people cheer when they see Rubin, smiling in his blue-tinted sunglasses and jeans and a blazer. Cake's cover of "I Will Survive" rumbles from patio speakers at the Hard Rock Café next door. The ground shivers with the constant growl of traffic, Interstate 45 just overhead. Houston heat is unmaneuverable. Most of the 300 neatly dressed men and women are excited, sweat-stained but excited, Peterson's book crimped to their ribs.

The evening sky is an upcycle of apparitions. Pink, blue, purple, orange. Untrammeled blizzards of cambion bright, scoping down over fields and skyscrapers, across broad land that used to be swamps and rice fields, now smudged with houses or concrete or highway. Somewhere spirited in the cartoon locality of it all, God exists. I've got all my life to live, I've got all my love to give. Eleven days ago, a trench-coated 17-year-old brandishing a Remington shotgun and a .38-caliber revolver barged into art class at Santa Fe High School, 30 miles south of here, and murdered eight students and two teachers.

Peterson and Tammy greet people in the line. Peterson poses for pictures, shakes hands, nods as people spill open with their stories and affection. He seems more lively than he did earlier, or at least he's lost the scowl.

A young man in a casual suit, followed by his friend, leaves his place in line to shake Rubin's hand, thanking him for his conviction to stand by what he believes. I will survive, I will survive. They're interrupted by a woman in a sundress who asks for a picture with Rubin. Peterson rushes into the frame, grins with practiced excellence, then nods. Just as quickly, he strolls up the craggy stairway into the venue's air-conditioned lobby.

In the green room, Rubin leans onto a padded leather chair near the doorway. Peterson takes the loveseat. He hunches over a makeshift table, talking and gesticulating and peering down occasionally to sign posters one by one from a stack of high-gloss prints, each labeled with a different rule from "12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos."

According to Peterson, people at his shows almost never talk about politics. Most of them want to talk about personal development.

“You know," he says, “it's rare that I don't meet two or three people who said they were at the end of their tether, and that they're back on track. Too many drugs, too much alcohol, too much depression." He estimates the ratio of personal development to politics at 25-to-1.

I assume he's telling the truth, but anyone who's followed Peterson's journey will understand why I'm also skeptical. The man is popular by dint of his political actions. He'd been a professor and clinical psychologist for two decades, but it was his opposition to the Canadian Bill C-16 in September 2016 that first made him famous. The policy requires people to use preferred gender pronouns for transgender or nonbinary people. Peterson said no. He saw it as a violation of free speech and rallied online, making it clear that he would refuse to obey the law, even as a professor, so bring on the jail time.

One online audience saw his reaction as transphobic, then began spreading the idea that Peterson is a Nazi, or at the very least a bigot or an ideologue. Another online audience secretly admired his boldness, his willingness to say no and stick by it; and when they discovered Peterson's cache of lectures on YouTube, they liked his no-nonsense approach and motivational absolutism. Many also enjoyed his unabashed masculinity and disdain for communism — both of which only further upset the anti-Peterson crowd, and were among the elements co-opted by the "alt-right," which Peterson has unequivocally repudiated. Nonetheless, it's an association that, right or wrong, his critics will likely always consider unbroken. Each controversy has intensified pro- and anti-Peterson divisions in a feedback loop that even the craftiest PR team could not have designed.

Each controversy brings more critics, but also fresh converts, who often see criticism of Peterson as needless persecution. Most of his followers are ordinary people like you and me, but the more fanatical ones have a cultish glaze to their eyes. To be fair, Peterson critics tend to be raving lunatics, unable to actually listen to the guy before trumpeting their opinions full of ad hominem. Neither side is able to listen to the other. Their respective understandings of who Peterson is varies so radically that it's hard to believe they're talking about the same person. To his critics, he's a political villain, hellbent on enforcing the oppressive norms of the past. To his supporters, he's a cultural hero, standing up for what's right, devoted to making the world better... To see this fight in action, browse through the Reddit war between r/JordanPeterson and r/EnoughPetersonSpam.

This ideological tug-of-war is part of what binds Peterson to the so-called Intellectual Dark Web, a collective of academics, journalists, podcasters, and professors, that has slowly evolved from a loose counterculture to a sociopolitical movement, and continues to gain followers and opponents by the hour. When I ask Peterson what makes the movement so appealing, he tells me that people are sick of the condescension of legacy media and that none of the Intellectual Dark Web members considers their audience stupid. He then mentions something about pedestals and people breaking their necks. Metaphorically, I assume. As Peterson talks, he glides his hand along a poster, “Rule 10: Be precise in your speech."

At the same time, it's not fair to depict the "12 Rules for Life" tour as a purely political event. It's not. Yet most respectable journalists still describe it as a more civilized version of Trump rallies, a sideshow of flexing hetero-masculinity, a kind of right-wing rally where angry, sex-starved white men hone their capitalistic, misogynistic, transphobic urges.

“Yeah it's a real hate rally out there," Rubin says with a grin. Then his face straightens. “Jordan goes up there every night and talks about how the identity politics of the right are as dangerous as the identity politics of the left. I think I can speak for most of us here — most of us came from the left. So we're more sensitive to what's happened to the left. But literally every night I ask him in the Q&A if he doesn't get to it, 'What do you think of the 'alt-right'? What do you think of that brand of identity politics?' Everything he does is about the individual — the individual is the cure for racism, for prejudice, for bigotry. So I mean this is just because of their lazy thinking — they're not journalists, they're activists."

Peterson adds that the ideal relationship between journalist and subject should be “a voyage of mutual discovery," based on mutual trust, which he relates to “Rule 9: Assume the person you're listening to knows something you don't."

I nod OK.

“If you listen to people, they'll tell you everything," he says, sliding a poster onto the growing stack beside him. “You have to be ready for what they'll tell you. And that's the thing, you actually have to be willing to hear what they have to say."

So journalists haven't been listening to his message?

Peterson balks at the idea. “They haven't been listening at all."

He adds that many of the interviews he's done have been downright comical. But he believes that audiences are sophisticated enough to decide for themselves: “Certainly much more sophisticated than many of the people who are still players in the mainstream think."

So what about the media's portrayal of him as a savior to a generation of young men?

“Well, first of all, there could be worse things to be portrayed as, right? So, I don't have an objection to that, per se, although I think that there are underhanded reasons that it's happening," he says, eyeing a poster. “Part of the reason the journalist types pigeonhole me, and turn this into something political, is that they can't imagine that there couldn't be anything other than the political. And so they don't know how to cope with, let's say, the psychological, they're not sure exactly what it is that I'm doing, in their own terms, although obviously I'm not a friend of the radical left, so, their easiest response is, 'Oh, you must be the voice of the disaffected, angry, often white, man.' No, sorry, not true."

Rubin, voice low and calm, brow relaxed: “You should try to get a feel for how 'angry' everybody is out there tonight, because you're gonna see nothing but love. And that feeling is what [the media] are so afraid of. Because they can't believe that people are coming together and are accepting differences."

A slow, grocery-store jazz song begins playing over the theater speakers.

“I think the one thing that unites us," Rubin continues, “beyond what Jordan said about the respect we have for our audiences, is that there's a little humility here. We don't have all the answers."

Peterson nods. Something about his expression reminds me of Tennyson's Ulysses, who begins the poem salty then builds into a rousing speech. He cannot rest from travel. How dull it is for him to pause. I ask Peterson if anything has surprised him along the tour.

“Encouragement — that's the fundamental issue," he says. “I'm amazed at how many people there are who haven't had any real encouragement at all in their life, and how much of a hunger there is for that, and how effective it is to do it, to remind people that there's more to them than they think, and, I would say also that they're likely to find the most profound meaning in their life through the adoption of responsibility, which, in some ways — it's so funny — in some ways, you don't have to think about that very long before it becomes evident. There's a place for fun and all of that, but when you think about what sustains you over the decades, it's your commitment to things that matter."

Encouragement, dialogue, mutual discovery, intellectual voyages, trust, listening — it sounds a lot like counseling, I say. Is the relationship between him and his audience similar to the relationship he shares with clients as a clinical psychologist?

Sort of, he says, although it's closer to the professor-student relationship, with an emphasis on dialogue.

“I don't talk about things that aren't of practical utility," Peterson says. “Like even if they're very abstract, I try to make sure the abstraction is brought down to the implementable level. It's also because I was trained as a behavioral psychologist, and there's a rule if you're a behavioral psychologist: Always make something implementable. Break it down to the point where it's implementable. And measurable. So that people can chart their progress."

Peterson looks down: The stack of unsigned posters is gone.

Rubin shares a few words with Peterson, then joins me in the hall. He nods and I follow him onto the stage. He paces lightly to the front of it, looks out at the empty room, at the rows of folded-up chairs. “It's the stand-up [comic] in me," he says. “I love to get a feel for the room. Each room has its own feel."

His smile has a direct, genuine warmth to it. Rubin, unlike Peterson, encapsulates the oneness of a group of people David Foster Wallace predicted 25 years ago, a group he called the anti-rebels, “born oglers who dare somehow to back away from ironic watching, who have the childish gall actually to endorse and instantiate single-entendre principles. Who treat of plain old untrendy human troubles and emotions in U.S. life with reverence and conviction. Who eschew self-consciousness and hip fatigue."

The rumble of an audience grows louder. Rubin smiles.

Most of the tour's venues have been ornate theaters and fusty opera houses, so the Revention's gymnasium aesthetic is a refreshing change. In Philadelphia, the audience practically arched onto the stage, so close that it was almost distracting. “This is a little more like San Francisco," he says, “which I like. It's got more of a seat."

Half of the air smells cold, half of it burnt, like old electronics. The pre-show music is drab elevator jazz that Rubin groans at, “Usually they play something better than this before the show. Music that gets people going."

Today, the entire city of Houston slugs around, mopey after last night's embarrassment. The Rockets lost game 7 of the NBA Western Conference finals, missing a record 27 three-pointers in a row near the end. Rubin debates whether or not to start the show with references to the game. Maybe it's too soon.

The tour has taken over Rubin's life. “But it's been great," he clarifies. He's touring with Peterson as much as he's able to. All of May, June, July, then returning to L.A. anytime he needs to record "The Rubin Report." In August, he's locking his phone in a safe for the entire month — total disconnection.

“I'll need it after this," he says. “This has been nuts. I'm loving it. It feels great. It's incredible. Seeing what we're seeing. It's so validating and wonderful. But you've got to have a break." He's going to challenge people to do the same. To disconnect from the chaos and vitiation of politics and news and a culture at war. “If you're gonna do it, August is the right time to do it — end the summer without the madness. Yes, you'll miss some shit, but, guess what, the world keeps going."

* * *

The audience whistles and cheers when John O'Connell announces that no heckling will be allowed during the show. Rubin takes the stage, warms the crowd with a stand-up routine. Backstage left, Peterson paces a little, stiff in his navy blue suit, burnt-orange tie with traces of blue, black socks and brown dress shoes that lace into a stubby leather nose. Hands clasped behind his back, head tilted, lipping words to himself. He peeks out at the well-dressed crowd. They stare ahead, pacific and ready.

Rubin references Nellie Bowles' article “Jordan Peterson, Custodian of the Patriarchy," the most recent Peterson hit-piece. “According to the New York Times," Rubin says, “Jordan is for 'forced monogamy'." The audience laughs then groans at the thought of it. “Which sounds like something from 'The Handmaid's Tale' … But…it's actually just marriage, people …" With a Woody Allen chuff. “Which is even scarier, actually."

* * *

In a tufted chair, Peterson tells the audience that he was recently invited to write the preface for the 50th anniversary of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's "The Gulag Archipelago," a book that he references frequently and credits with effectively dismembering communism. It's the first time he's read the material to an audience and he'll spend most of the hour and a half show reading it. The entire room draws into silence as he weaves along the dark, obscure coils of the writing.

Just as the mood is approaching morose, Rubin returns to the stage for the Q&A. He chooses the questions cleverly. One about psychedelic drugs, then, “Will you say a curse word?" Afraid not, Peterson answers, with a heavy laugh that hurricanes into his headset microphone, the kind worn exclusively by motivational speakers and Garth Brooks.

“Here's a good one," Rubin says. “'Do you think we should colonize other planets?'"

Peterson, with a grin, “Knock yourself out, man." The audience laughs. He smiles, waiting for them to finish, watching their faces. “I remember the moon landing," he says, “we need a collective like that to remember who we are. So if we go to Mars, all the luck to the crazy bastards who do it ... and there's your curse word."

Three thousand faces lean forward, lingering, as Rubin gazes at the MacBook screen for the next question and turns to Peterson: “What makes you happy?"

Rested into the coal-grey chair, Peterson meditates, rummaging the answer around into something implementable. He smiles, glides his hand toward the audience, then back to himself and Rubin. “This makes me happy," he says. “I'm so struck by this hunger for discourse that's spread through society in the past few years."

“Keep it going," someone yells.

“Human beings, we're just so noble, man, and spirited, that we can use the gifts that we've been given and make the world better."

“Keep it going!"

John O'Connell, with an avuncular smile as he watches Peterson, tells me again that Henry Rollins often inspires the same humanity from crowds, from people who felt lost or broken. People who would cry alone, and now they can live like they wanted to, and they tell him that he saved their lives and no words could ever thank him enough. Every stop of the tour. Critics of Peterson see this as cult behavior.

Rubin waves to the audience then ambles off stage. He's meeting some fans of "The Rubin Report" for dinner. I tell him I'll see him tomorrow in Dallas. Peterson is still on stage, tittering his hand in a wave. The audience bellows. An engrossing draft spurs the room. Each cheer continues even after it's gone. Bland jazz ramps through the speakers. The stage is grey and empty as the house lights dally. The aisles start to fill with slightly dazed people, polite like they've just been pulled from a dream they wish had kept going.

Outside the venue, people chatter and pretend to be normal, smoking cigarettes or exchanging glances or prodding at their phone. The sky glows above them like a violet lamp, over the winding streets arrogant with moss. Taxis and Ubers line up, imitating slugs. Casually, people leave. It is exactly 10:48p.m. and downtown Houston has slowed to a weeknight groan, encircled by clovers of highway. The city's emptiness feels like an insult. Pizza parlors have closed early. Bars linger, mostly vacant. Clubs flash without dancers dancing. Stadiums mope, clad in trash and fog. Ponds swarm with mosquitos. Churches and temples wait for a sign of life or hate or donation.

People file into the Majestic, a haunted old theater down the street from Dealey Plaza. Everyone is shouldered into bright red seats, an arrangement more suited to the early-1900s audience who first attended. The theater is beautiful, an American cathedral.

“No heckling will be permitted at tonight's show."

Applause.

Several times, Rubin says “I can feel something from you guys, this is going to be a good show." He stops for a moment, looks around, breathes deeply, says, “I can feel it tonight. Every one of these has been different, and I sense something special tonight." He then describes a tweet from a young man who was at the first show, in Toronto. “He took a picture of himself and his girlfriend," Rubin says, “and he wrote: 'It's wild to be sitting in a sold-out venue, with a thousand other people, waiting to listen to Jordan Peterson and Dave Rubin, when in my daily life, I act like a secret agent and tip-toe around even mentioning Jordan Peterson's name.'"

Rubin turns to the crowd, “No more secret agent stuff, people, you're all here. Look around, you're all here, I know you all watch these things, usually at your computer or on your phone alone, but look around. There are 3,000 people here right now and we're doing this all over the country and every show has been sold out. It is truly something awesome, and it's bubbling up, guys. Most revolutions are bloody, but this is an idea revolution."

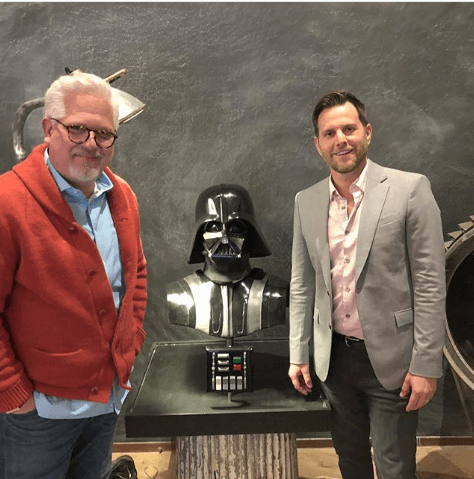

Midday Wednesday, Rubin arrived at Mercury Studios, home of Mercury Radio Arts and TheBlaze, and Glenn Beck gave him a tour. The glowing, roof-sized mural of Abe Lincoln made out of iridescent railroad spikes. All the artifacts and relics. Three gigantic studios, previously used for "Robocop," "JFK," and "Walker, Texas Ranger." After a few minutes, Rubin asked Glenn, "Where's Darth?"

Tonight, Peterson is much livelier than he was last night. He quips a few times about the Dallas crowd being easier to look at than the Houston crowd. In reality, there is no discernible difference between the two crowds, besides now having Glenn Beck in attendance. Tonight's audience has the exact reactions as last night's — it's that strange moment when multiple groups of people react the same way independently of one another. No doubt, Peterson and Rubin are part of a cultural tidal wave. And half of Peterson is in love with this moment; the other half responds to life like you or I would, flawed and sometimes ugly. Overall, he seems like a well-intentioned person trying to make an impact, but a person nonetheless, and occasionally he's a total jerk. Which is excusable, really. At times, it's necessary, given his fame and stature. But it shouldn't be the basis of a persona, as I suspect is becoming the case for Peterson. Aren't these strange times? That repeatedly saying “no" is such a revolutionary act?

After an hour-and-a-half rush through the first seven rules, Rubin joins Peterson on stage for the Q&A. The audience is quiet as Rubin gazes at the MacBook screen, skims a list of audience-submitted questions, then turns to Peterson: “I'll start with an easy one. 'How do you conceptualize God?'"

Everyone laughs except for Peterson.

“Carl Jung said that the highest value in your hierarchy of values serves the function of God," he says. “So imagine you met a hundred admirable people. And you distilled what was admirable about them into one person. That's what should be at the top. The thing that's at the top of the value hierarchy, that's the thing that makes the proper sacrifices, well that's part of what God is, that's part of the ultimate value."

As he talks, his hands glide along in surgical movements, almost preconceived. When he pauses for a moment, the theater constrains in silence, peasant-like and doting.

“The question is, 'Well exactly what is [God]?' And the answer is, you don't know, it's too damn complicated, you don't have a map. You can see pictures of it, you can see glimmers of it everywhere, there's stories about what it might be, it's whatever a human being could be if what a human being could be was fully manifest, was fully revealed. We don't know what that is. It's associated with something akin to divinity. And on that axiom our entire culture is predicated. And you throw that out at your peril."

The room is vast and cold, and the audience gapes ahead in wonder. Around the corner from the theater, lanky prostitutes stalk through a concrete park. Men in jumpsuits scowl over them. Homeless people caper down a mosaic of sidewalks, prowling for heroin. A little farther, Dealey Plaza. Kennedy murdered in broad daylight.

After the show, Rubin and Peterson and Glenn Beck chat in the dressing room. The thin hallway of a room has three sinks at the back and a curtain instead of a door veiling the toilet. A narrow, immovable hallway of a room, meant for actors about to take stage, each with a makeup desk and a mirror along the row of mirrors, each mirror festooned with globular light bulbs, the kind you see in upscale salons and Broadway billboards. All the bulbs in the front half of the room are dead. All four mirrors in the second half of the room have functioning lights.

In a curvature of shadow, Peterson slacks backward on the couch, elbows jutting into the beige, time-worn lumps of cushion and stitching and grit. He's nodding like a jazz musician after a long set. He fiddles with his wedding ring as he talks, then shifts his hands elsewhere, into the shape that's needed, depending on who's around.

It's Friday, June 29th, 2018, over a month since Peterson and Rubin were in Dallas. Tonight's show at the Long Beach Terrace Theater was originally Rubin's last stop on the tour, but Peterson has added new dates for September and October. I flew to L.A. on Thursday and met up with a photographer/videographer to prepare for the photo shoot and interview.

Long Beach smells like weed. A gentrified beach town, gritty with docks, a port city, 72 degrees in the shade, riven by an avenue lined with giraffe-like palm trees and buildings that smack with Miami resplendence, prim from neon paint that juts out in opposition to the sad, grey docks and the ocean view ruined by prowling tankers. Skateboarders glide around the entire city, so many skateboarders that it feels like a gag. They greatly outnumber the pedestrians and the homeless. On the whole, they are polite: Misfits dedicated to an arduous game. “Rule 11: Do Not Bother Children When They Are Skateboarding." Near the docks, there's an extreme sports tournament sponsored by Mountain Dew. From the crowded balcony overlooking the dirt mounds, you can stare out at the sailboats and the oil rigs and above all of it is a flame, proof that oil is down there, that it's worthwhile to keep digging.

I take it as a sign, that Peterson is worth the pursuit, that I have doubts about him but all I need to do is listen.

We have some time to kill. In search of a bar or restaurant, the photographer and I weave through an encampment of homeless people, then round the corner into what is obviously a club district. It is pure hedonism. Ancient Rome in high heels and polos, the air nasty with Jägermeister and vape smoke. We'd forgotten that it's Friday, so the Ibiza hip-hop and motorcycle revving are a bizarre yet lovely reminder. We find a patio table at a Greek restaurant where a waitress brings us Heinekens and ignites a skillet of cheese. Behind her on the sidewalk, leaned against the gate, two policemen grin at the flame. It's nice the way things circle back around.

* * *

The crowds coil into the building and Peterson is nowhere to be found. Rubin is 20 feet from the main entrance, with husband David Janet nearby, shaking hands and taking pictures with fans. Janet and I hug, skipping small talk so that we can tell each other how life has been since we last spoke in March.

Today has been a chaotic day for Rubin and Janet. Earlier, they filmed and hosted a livestream episode of "The Rubin Report" featuring Peterson, Ben Shapiro, and Eric Weinstein. Tonight, they have a midnight flight to New York. They'll be there 23 hours, then back to L.A. and who knows where next. Janet, backpack in tow, smiles as he tells me and the photographer about the chaos and excitement of the last few months. Rubin looks fresh, patrician in his greetings. The guards at the backstage entrance smile, point to the photographer, Janet, and me, then ask Rubin, “This is your entourage or your bodyguards?"

Janet smirks, “What — you don't think I can take him?"

The backstage area looks and feels like the inside of a Navy ship. The air is dusty and metallic, cold and half-lit and sterile. We wind through a maze of industrial rooms lined with tubes and safety helmets, then shove into a cloaked door, and suddenly we're behind the curtain, the purple satin fur reaching up to the ceiling and all its wires and can lights.

As the four of us turn a corner, Peterson pops his head out of a dressing room, spooked or half-awake, then shuffles out of the room, yanking the door shut behind him. We all say hello, begin to approach. He grumbles something about his room, shakes his head, shakes his head, looking gaunt and uneasy. “No," he says. Everyone stands there awkwardly for a moment. He backsteps into his dressing room and closes the door.

"Rule 6: Set your house in perfect order before you criticize the world."

Part of Peterson's allure is that he's willing to be rude. This curmudgeon quality reflects what Ben Shapiro calls the Bartleby instinct, the power of “I prefer not to." A puzzled twinge lingers in my gut. Regardless of whether I agree with Peterson's ideas or not, I, like many people, have admired his boldness to say, “No." To him, morality is not relative. Yes or no. Chaos or order. Jesus or spiders. He's unflappable. Nonetheless, I can say that it sucks to be on the receiving end of this rudeness.

After a quick silence, I follow Rubin. The conversation picks up where we'd left it as we prowl around for a room of our own. Janet gives up his seat beside Rubin. He has tons of work to do, but he sails his head up any time he has something to add to the conversation. Rubin and I talk about life, how it's overall a good thing. “What do you believe in more than anything else?" I ask him.

He widens his eyes for a moment, rolls his head backward, sighs a bit. “I believe that humans are innately good," he says, then allows the idea to float there alone.

“And I think virtually everyone wants to do good, and be good, and be decent to each other, and pursue something that is valuable to them, and meaningful. And then I think, what happens along the way is, bad actors get involved, and they're loud and convincing, and next thing you know, people have put away their innate good and they're chasing things that aren't so good.

“But I think one of the things we've been able to do with this Intellectual Dark Web crew is we've been able to get people a little bit to start thinking about what their role as an individual is. And if they can get their life a little bit in order, that then is how you start the process of getting society in order, as opposed to doing it from top-down, where, 'If only we had a President who was perfect, he could make everything wonderful for the rest of us.' When in fact it's actually you, the individual, that has to start it."

The air conditioner whirs all around us.

“I think we're innately good," he says. “But it doesn't mean we're gonna do good all the time. It means you have to strive."

In the corner under a glowing clock, Peterson lowers his head as if in prayer, deep in his own meditation. Lights. No heckling, applause. “... Jordan Peterson!" Stand for more clap. Hunch down in seat. Stare ahead.

During the show, the photographer embeds into the stage-right wing, prowling in for photos whenever he can get close enough. A 300-pound stagehand yanks him back with a single-arm wrestling move any time he gets too close, and, with Peterson talking about individuality 10 feet away, it turns into a high-brow Marx Brothers routine.

Peterson spends the hour-and-a-half discussing “Rule 1: Stand up straight with your shoulders back." He relates it to freedom of speech, and the darkness of a world without it. The show is marked by sporadic bursts of laughter from the crowd, but mostly they stare ahead in awe. People listen deeply. Peterson seems less interested in humor tonight, speaking over the audience anytime they start to laugh at something he says. At times, his pace borders on logorrhea. He seems casually irritated, and several times he calls the audience idiotic, insignificant, privileged — in a jocular, drill sergeant way. He's done a version of it at each show. Audiences love it. I can't tell if it's the good attitude of people who can laugh at themselves or some kind of intellectual BDSM.

Critics see it is as textbook cult behavior, proof that Peterson is a pseudo-intellectual conman. Followers see it as self-improvement or entertainment, something they hear and feel less alone. Critics frown: Self-improvement, they balk … more like indoctrination … Entertainment, they balk … oppression is a dangerous thing to be entertained by. Followers mention something about far-Left indoctrination and oppression at universities, then add that we live in a humorless time, so lighten up and don't make this political for once, snowflake. Critics reply that they're not the ones who need to lighten up, Nazi. Yes they are, followers say. Critics punch back. Followers duck, then punch. Punch. Punch. Back and forth, back and forth, dancing around the hordes of unclaimed people standing awkwardly in between, people like you and me who just want a decent life or some middle ground, not sure who to believe, getting tired of this either/or game.

Near Peterson's feet, a small digital clock with bold red numbers flashes, counting down, angled so that he can see what's left. Rubin emerges for the Q&A. He and Peterson banter. Off stage, Janet and I talk about life and marriage and Netflix.

After the show, Peterson strolls off, giddy and electric, then shakes hands with Rubin and John O'Connell and some people from Live Nation. Rubin and Janet chat, leaning into one another so they can decide how they'll get to the airport in time.

After a quick jaunt to the dressing room, Peterson returns to the stage to take photos with the VIP crowd, 400 or so people with pamphlet-sized laminates, who pose one by one in front of a lined backdrop with the abbreviation "OMG" repeated 30 or so times. John O'Connell snaps the photos, shrugging but still friendly. The line curls around the theater, four people deep at certain parts. No doubt, Peterson will be here for hours, somehow able to smile and converse and engage with fans on an emotional level, or at least give the appearance of it, friendly like a gaunt Santa Claus, stuck at the mall forever.

I sneak a glimpse at him as the photographer and I leave the theater. I feel a sinking ache — something about Peterson in front of that blue and yellow tarp covered with that dumb abbreviation. Each person huddles into him, and he huddles back. They adore him. Can you believe it: He and Henry Rollins, madman of 80s punk, elicit the same adoration? Every person in line has a wish, something they'll say or ask for. Despite his good attitude, Peterson looks like a corporatized Socrates, busking among selfie sticks and nippy chatter. Sometimes it's sad to see how a person actually makes their money. On the other hand, what's wrong with getting paid? What's wrong with becoming famous and making money ? And can you blame him? Would you do all this for free? Would you do all this at all? Most of the people seem genuinely happy to pay the extra $50, so who's the victim? ... OMG OMG OMG OMG OMG...