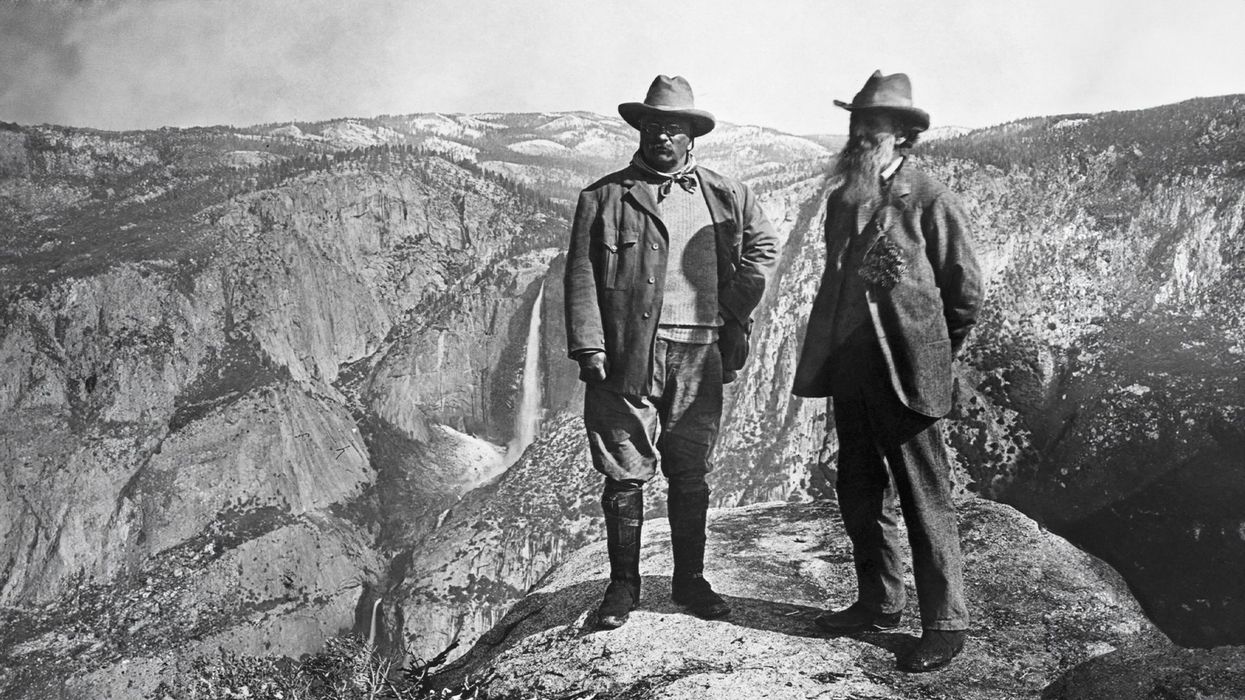

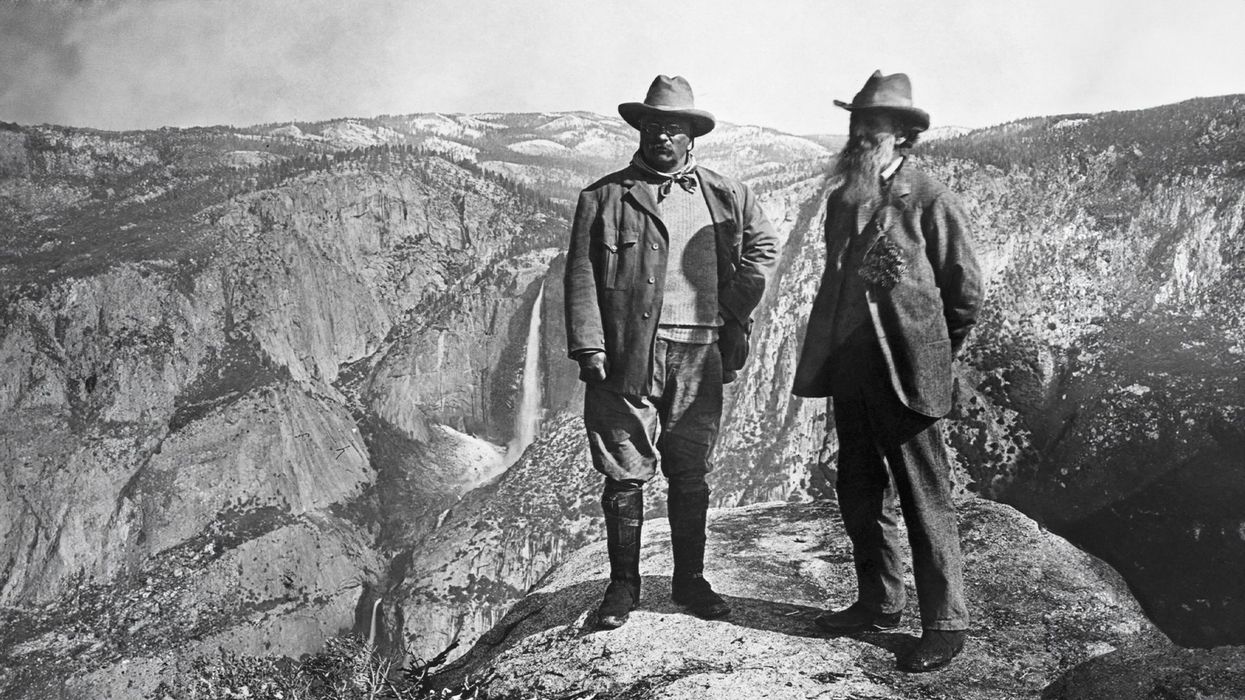

Bettman / Contributor

Touching grass with John Muir, America’s founding conservationist.

There is a figure whose faint whisper blows from the 19th century—ever westward, toward a land whose industrialists are exceeded in their ambitions only by the sheer limitations of its indomitable landscape. He tells his contemporary dynamists, and ours, to embark on the most seemingly impractical of efforts: to “spend a week in the woods,” to “break clear away, once in a while, and climb a mountain,” to “keep close to nature’s heart.”

Muir was, first and foremost, a man driven by the sacred spoken into creation by a voice that still echoes through the remote and untouched landscapes of America’s West.

This quiet, gentle figure, John Muir, is one of America’s great explorers, the first to travel into California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains. If you have ever been to Northern California, you have likely encountered his name, whether on the John Muir Trail, deep in the Muir Woods, or at countless other nature sites that bear his namesake. His legacy, compared to that of the Rockefellers, the Carnegies, and his contemporaries “back East,” appears trivial to our 21st-century eyes, still conditioned by our industrialist forefathers. Against that warped vision, Muir aspired to bring a well-balanced corrective.

You might know him as America’s “first conservationist,” a man who worked alongside Theodore Roosevelt to found the National Parks Service and to preserve America’s most spectacular landscapes. Yet quaintly remembering Muir as a mere “explorer” or “conservationist” runs the risk of misrepresenting the man to fit modern political agendas—as indeed has happened—and in so doing, of warding off the vigorous spirit that drove this native Scotsman into California’s most remote peaks and ranges.

Muir is distinct from the explorers who traversed America’s landscape to conquer new territories or glean financial gain. He went into the mountains for the same reason that one goes into places of worship: to “get their good tidings,” to reap some ancient wisdom that cannot be found outside the sacredness contained in that space. This cannot be pursued for any reason other than to entice a man toward encountering the divine.

Muir was, first and foremost, a man driven by the sacred, not in holy edifices built by man but spoken into creation by a voice that still echoes through the remote and untouched landscapes of America’s West. He believed that the same Holy Spirit that nourishes the soul through hallowed hymns within cathedral walls could be felt in the songs of birds and in the rustling of Sequoias carried upon the mountain wind through the valleys of Yosemite.

Environmentalists have since attempted to co-opt Muir’s legacy for their agenda, one that champions nature’s good above

man’s. Muir sought to conserve America’s landscapes, but not because he saw in man something separate from and unequal to the blameless natural world. On the contrary, Muir saw man as the penultimate member of God’s divine order. Nature exists to provide vital nourishment for man’s soul, and positing its value above that of man’s would deprive it—and us—of the very reason we ought to conserve.

Expressed through Muir, this inextricable bond between man, nature, and the divine presented him to his century as one of the precious few public figures to resist its mania for reducing man to a unit of utility—denying his soul, Muir believed, indeed his very essence. Man cannot live on bread alone; he “needs beauty as well as bread, places to play in and pray in, where nature may heal and give strength to body and soul alike.”

We can look back on Muir’s contemporaries like the Rockefellers and the Fords with gratitude for building America up as the world’s leading industrial empire, one whose spoils we still—albeit with increasing uncertainty—enjoy today. In the 150 years that sit between us and Muir, industrialist reductionism has sown the seeds of collectivism, eugenics, genocide, and alienation, a bitter harvest whose legacy we have by no means put behind us.

We should not be so naive as to think that we are immune to these dark tendencies of our inherited industrial tradition. How many world leaders are championing anti-human globalist policies at the expense of the human person? How often do we act as if our value is determined by our daily means of production, accomplishments, and other material things extraneous to our souls? Muir reminds us the divine inhabits the streams and mountains, the crimson sunset and dark grays of storms coming in off the ocean; not the concrete temples of man’s grandiose.

Katarina Bradford is the assistant editor of Frontier. She has contributed to several publications including Blaze Media, Return, and Evie Magazine.

Katarina Pfister