Glenn Beck is using these historical artifacts to make history come alive.

Blaze Media Editor in Chief Matthew J. Peterson sits down with Glenn Beck to discuss his fight to preserve the American story.

The Collector wants preservation. He collects artifacts, engines, watches, books, paintings, and documents. He is struck by an impulse to save civilization before it disintegrates. There’s nothing organic about this disintegration. It’s a full-fledged attack by ideologues and activists eager to destroy anything sacred.

Glenn Beck is a collector. From his days at radio stations throughout the country, he climbed to the top of conservative media. Forbes once passive-aggressively claimed he “managed to monetize virtually everything that comes out of his mouth.”

They’re right, to an extent. He’s a rare balance of creativity and business acumen. Not only does he earn his wages, but he also invests them in a kind of humanitarianism far more fruitful than that of the headline-grabbing protestors who glue their palms to Manets.

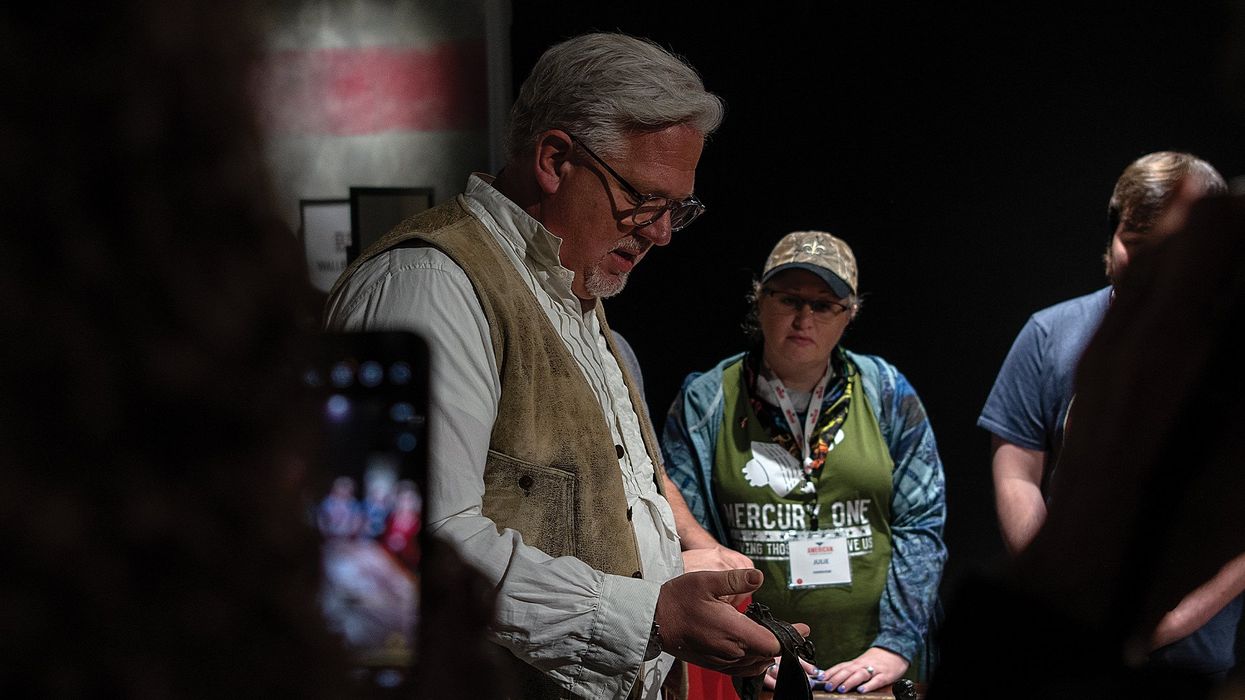

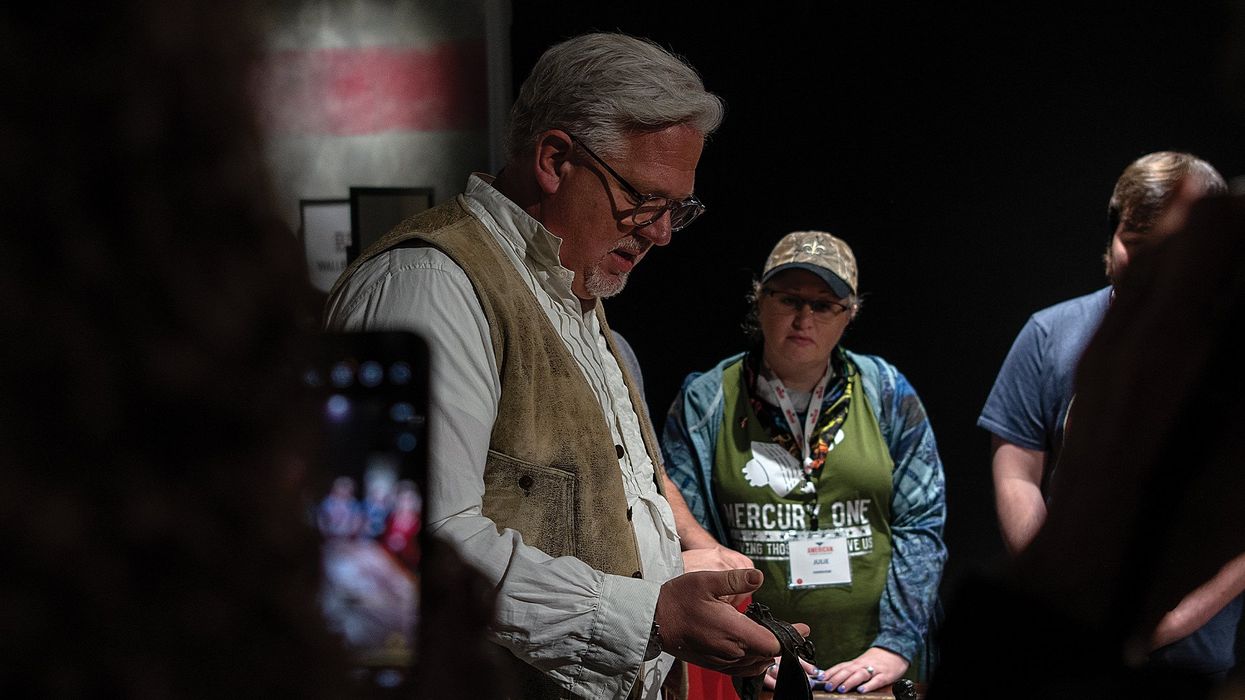

Beck is rushing to preserve the valuable relics of a nation on the edge. He treats this as a duty, a spiritual and patriotic duty. Even Mercury Studios, the Dallas headquarters of Blaze Media, is proof of his preservation campaign: It was formerly the Middle America hub of Paramount Studios, which Glenn renamed in honor of Orson Welles’s theater company.

Walk through Mercury Studios, and you’ll see some of the unique cultural treasures he’s collected: the “Life is like a box of chocolates” bench from Forrest Gump, the original Darth Vader suit, and Dorothy’s glittery slippers. These comprise but a tiny part of his collection.

MATTHEW J. PETERSON: How do you reckon this started?

GLENN BECK: I grew up as an old soul, and I knew what I wanted to do when I was eight because my mother gave me a record, The Golden Years of Radio, which hangs right outside my studio.

But this collection is different because it started because of a prompting I had in my prayers. It was 2009, and every day, I would pray three times a day, and I would pray and pray and pray, and I started hearing clay pots. Now, that’s either a sign of insanity or God’s trying to tell me something, and I remember because I have a very interesting ... a very “Israel”—relationship with God.

I wrestle with him often, and I’m like, come on, man. You created me. I did not. You got to give me more than that. And every day for months, clay pots, clay pots, clay pots. I don’t know what that means. So I don’t know what you want me to do.

And then one day, I was on the air, and

I said the people we are dealing with hate America so much. It’s not that they want to just change it. They will destroy it and erase it. There will come a time when people will actually believe America never went to the moon. When I said that, those who did not believe we went to the moon were at 7%. The last I saw, it was 16%.

I said they will take our sacred American documents, the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, and they will destroy them. And when I said they will take our sacred American documents, it almost took my breath away. I struggled to continue after the break because I understood clay pots. I fear that I will get up to the other side, and he will be like, nope, that’s not what I meant.

But I realized the Dead Sea Scrolls were put into clay pots. Why were they put into clay pots? Because a small band of people took what they had outside the canon and pushed it into a cave, where it was lost for 2,000 years. It wasn’t that it was necessarily so new—some of it was—but it verified what we thought we knew was true.

MP: Can you tell us about your upcoming art show?

GB: I’ve been working with some of the best artists in America who are tired of painting landscapes and other things. We’ve worked with people from Pixar, and I’ve had all these artists up for two or three years every summer. So this fall, they’re doing a show with an opening for the public to see the museum. They’re coming and doing a show of their art with an artifact. So we told them a story. They could pick whatever they wanted, they choose an artifact, and it’s twofold– buy the art for the artists; encourage them to tell the stories; but also, for people who can’t necessarily afford art, they come, and there’s a prize given at the end for the artist for the one who reflected the story the best.

MP: And that’s what you did? Which one told the story the best? How have you gone about saving this history?

GB: And so I’ve interpreted it in a couple of ways. We’re opening the museum this fall. I was in Italy last year, the year before, just outside Florence, and these little teeny towns sit on the top of hills, so they had the advantage militarily. And there are these villages that have been there for 2,000 years. And I went into one church: very, very dark, small windows. But instead of stained glass windows, paintings were all over the walls and were hard to see. But it was the story of Christ, his birth, some of the saints, and everything else.

And I stood there, and I thought stained glass windows and before that, these paintings on the church ... no one could read. And the story is who we are. Our story is being destroyed right now, being rewritten in real-time. We must paint, film, learn to tell, and collect the story of America.

That’s why we started with the founding documents. I went to David Barton and asked David what the essential documents would be if we lost everything else. That must we preserve? We preserve those. That grew into his collection, my collection, Mercury One Studio. It’s the third largest collection of the Founding outside the National Archives in the Library of Congress.

And then we just branched off. We now have the largest collection. We won a war with the Smithsonian. They really wanted this collection. It’s the largest collection of the Pilgrims and Jamestown. And that is one of our most important stories because it’s so amazing. We are having the same argument we had in the 1850s before the Civil War. Are we the people of Jamestown, or are we the people of Plymouth?

Plymouth is entirely different. If you choose Jamestown, you choose the story of slavery and oppression and everything that comes from the bad route. If you choose Plymouth, you get all the blessings of freedom. And which one are we?

We didn’t know because William Bradford’s diary, which contained all the history of the Pilgrims that he wrote, was lost. During the Revolutionary War, the British took it, and no one knew where it was. In the 1850s, an old guy retired from a church in England, and a new guy came in. The library was a mess, and he started organizing it. He pulled out this collection of papers.

He starts reading them, and he’s like, this is the story of the Pilgrims. This is William Bradford. And it’s now in the British Museum, but they made a copy for us right before the Civil War and gave us the truth on the Pilgrims, so we had that evidence.

And that swept the country really from the 1850s to the 1870s. We kind of went, no, we’re not Jamestown, we’re this. And that’s exactly the choice we need to make again. But we have the documents. All we have to do is, I mean, I can prove the 1619 Project wrong a thousand different ways. For one, we have the manifest of the ship, which they say was full of slaves. I have the starting of slavery in the Western Hemisphere from the Spanish to Brazil 30 years, 40 years before it ever came to America. I have the actual document. We have the document from the Spaniards to the Cubans and the Cubans saying we can now introduce slaves into America 20 years before the 1619 project.

The Spaniards brought them to Cuba, then they established this Spanish settlement in a place we now call Florida, and they introduced slavery there. I mean, slavery happened; it’s awful, but why don’t we get the story right? So it was essential to preserve all this. If you go into the museum now, you have about 1% of the collection because the rest is in the side of a mountain, a couple of mountains. Many important things now have a copy because they need to be protected. I fear what’s coming, and they just have to be preserved.

I took the clay pots idea and thought it meant putting them on the side of a mountain. We could put them in a granite vault on the side of a mountain. I know this; I’ve looked at it, we’ve talked about it, and I decided that we have to protect those; however, like the Dead Sea Scrolls, copies are what matter. So, this summer, we are starting with that list of essential documents.

So we will make good-quality copies on acid-free paper, vacuum-seal them, and remove them; you can buy them. We’ll make copies of all the essential documents of the story of America for each part of the collection.

And then you can buy whatever you want. But if we can get it into the hands of a million people, it’s a better way to preserve it because they can’t get all of it. They could open the vault door because it’s clear where those mountain vaults are, but they can’t get all of them if we enlist everybody. It’s interesting, isn’t it? If there was any justification for the government’s involvement in education, it’s that. It is to teach our history, civic meaning, and civics.

MP: Can you talk a bit about some of the dangers to history? Talk about what you’ve seen and experienced regarding people who want to desecrate or destroy these artifacts and stories.

GB: We know that we have been bidding against people that either will hide or destroy. We were bidding for the bell of the Santa Maria, but it wasn’t known to exist because it was sunk in a ship in the Americas. One guy spent his life looking for that ship, and then we know it’s the bell of the Santa Maria because Christopher Columbus’s grandson said, I have nothing from my grandfather because it’s sitting in the New World. It’s his desk and the bell of the Santa Maria, which is the one that rang first to say “land.” After that, they took the Santa Maria apart and built a church with it, so it was the first church bell in the Americas.

He asked for it back; it was put onto a ship. The ship had a certain kind of gold, and the coins were only made for that ship on that date. This guy has been looking for it his whole life; he finds it at the bottom of the ocean; it has the coins fused to it.

But I lost the auction. The first guy, the guy who had the highest bid? When the seller said Columbus was a son of a bitch. Melt this thing down.

The second guy said almost the same thing. He said, I don’t know, you’re not buying it. We had made a verbal deal on it. He’s from Spain, he fought for ten years, the Spanish said, No, that’s ours, belongs to us. He said, International waters, it belongs to me. He went back to Spain during COVID; we’ve lost contact with him now, and we don’t know what happened to the bell.

MP: Can you tell people how they can help or assist in this effort and the ways for people to get involved in preserving and helping you preserve these things?

GB: We have hundreds of thousands of documents. We now have a new machine that will scan them, digitize them, translate them into any known language, and put them online on the blockchain so they can never be lost. That’s the other clay pot. Just that one machine costs about $100,000. We need any kind of support. We’d love to hear from you if you want to volunteer and scan. If you want to volunteer and do research because we do extensive research on each product and project, contact us. If you’re like that internet worm who loves to find all the details, we want them. If you can help us collect them and you have the resources, great.

MP: Is there anything else that we should talk about in terms of ways to help?

GB: So one of the things: I’m coming out with a book called Chasing Embers. It’s my first young adult book, and it is a dystopian futuristic tale, but it’s a story I wrote in my head 20 years ago, weirdly by reading Karl Marx because I read it, and I’m like, this doesn’t even make sense. This is nonsense. How can this be so popular with youth? Because it’s rebellious, it’s forbidden; it’s something different. And I thought the biggest revolutionaries in the world were Thomas Jefferson, Ben Franklin, and Madison.

How did they become so uncool? Because that’s the accepted thing. And I realized that at that time, I thought, you know what, these guys will become calm again when they’re banned. And so I started thinking about this dystopian world, 50, 100 years from now, where truth is lost. Everything about the Great Reset, I mean, I wrote it before the Great Reset, but everything that the Great Reset was supposed to do—15-minute cities and nobody’s-going-anywhere kind of stuff—takes a dark, dark, dark turn, and now you don’t know what truth is.

The older people who remembered it tried to pass it on to their kids, but they were the rebels outside the city, and everybody was being told they were dangerous and crazy. All they were trying to do was collect books that could be found, collect people’s memories, and try to bring history back together.

So that’s for young adults. It’s a great adventure story, but it has little jump-off points that hopefully people will go, well, wait a minute, is that even true? Who is that? I’ve never heard that name before. You’ll be able to go to the website, and we have the documents from the library. And hopefully, we will try to get some people or kids interested in history.

MP: That is awesome. I want to go back to some personal things here. You mentioned your wife in the beginning. What about her journey in this revolution?

GB: So there were a couple of things. I think there were two breaking points with her, which involved chairs early on. Now she’s kind of gone dead inside [laughs], and she’ll just say, What did that cost us? The first one was a chair that was used for interrogations by the Nazis. And it was for persons of interest. As somebody who was on the air during 9/11 and the beginning of Homeland Security, I can’t tell you how many times I said they’re picking up persons of interest. And it takes on a different tone when you have the Nazis. And it’s this interrogation chair that has straps. Anyway, underneath, roughly translated, it’s the Deutschland Department of Homeland Security. The brand is on the bottom of the chair. And so I bought that, and she said, that’s not coming into the house. But then FDR’s wheelchair came up for sale. And I couldn’t even believe that, I mean, that we have so many things that I’m like, Wait, wait, I could buy that? Could we have that? And I think, FDR, that wheelchair, should be the symbol of FDR. That should have been the most significant thing because he went and destroyed the people who said people like him should be gassed and killed. A guy who was in a wheelchair was the turning point to stop that madness. And he hid it. So I think it’s one of the most striking pieces because of who it was when it happened and what he stopped.

So I bought that. My wife said, And what will we do with FDR’s wheelchair?

MP: Yeah, the truth is always better. Do you ever just sit and think, I can’t believe I’m doing this? I can’t believe I have this stuff. Or is this so missional for you now that ...

GB: It’s for the next generation. So, I don’t consider myself the owner of any of this. I’m the guardian of this for my generation, and then it will go to somebody else.

MP: Any idea how much worse it’s going to get?

GB: Oh, it will get much worse before it gets better. There is a perfect chance that in two generations, no one will believe America went to space or the moon. It’ll be another country. It’ll be Russia.

I could say more about this. I could tell you that we have been a Judeo-Christian nation forever. NASA can prove it, and I could tell you a story or show you the artifact. I would have never thought NASA had anything to do with Judeo-Christianity. We have the chalice used to take Communion by Buzz Aldrin in space. Okay, well, that is a personal thing. But they also printed 100 Bibles in micro-dot, okay? And we have two of them. They brought 99 back. I have two of them. My question was, where’s the 100th? They said it was left on the moon. That was their answer. We did our research and said, What, did they just open the door and push it out, and it’s floating? Where is it?

It’s on the altar that the Apollo erected—I think 17—astronauts. They erected an altar, then dedicated it to Almighty God, and then put that micro-dot Bible on the center of the altar where it still sits today. You have to recognize why Moses is in the center of the Congressional gallery where we see the president give his State of the Union. Right up above that is Moses. Right in front of the Supreme Court is Moses.

Matthew Peterson

Former Editor in Chief