NASA

A conversation with Tobias Huber and Byrne Hobart about their new book exploring technology, theology, economics, and the limitless potential of American ingenuity.

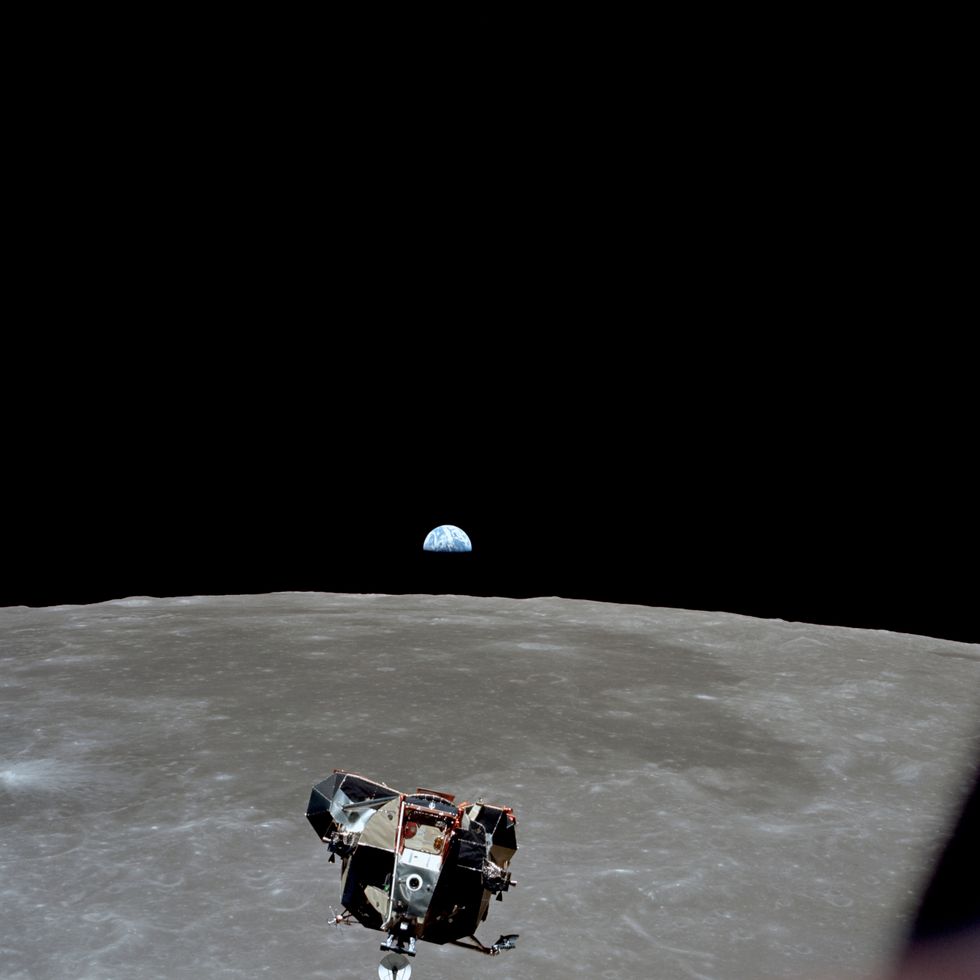

Boom: Bubbles and the End of Stagnation—the new Stripe Press book by Tobias Huber and Byrne Hobart—arrived with a bang. With striking images of the Apollo missions adorning the pages of their work, the authors aimed to continue the bold march of progress into the future while paying homage to the visionaries of the past. The intended effect was to convey American futurism in the 21st century, to which their book is a remarkable testament. Embraced by the likes of Peter Thiel and Marc Andreessen, the syncretic manifesto—which synthesizes insights from tech, history, philosophy, and theology—became, in the words of one techno-optimist influencer, the “new based tech-bible.” In this conversation with Frontier, the authors discuss the motivations behind their book, the ideas that catalyzed it, their collaboration, and what they hope to achieve with their bold exploration of the nature of techno-scientific progress and the causes of civilizational stagnation and decay.

Frontier: How did you two meet?

Tobias Huber: Online. We both share a rare interest in the obscure zone where markets, theology, and philosophy intersect. I discovered one of Byrne’s posts on financial bubbles through the lens of Gnostic heresies and sent him an email. He replied that he had already drafted a message to reach out to me after reading a piece I wrote on bubbles as innovation accelerators.

This marked the beginning of an endless torrent of messages, which culminated in a paper applying René Girard’s mimetic theory to financial markets.

Frontier: Why Girard and mimetic theory?

Byrne Hobart: Girard was a literary theorist, and stories always have some material conditions that affect them but also involve timeless motivations. So that’s a nice framework for writing about technology and human motivations.

TH: I have a background in philosophy, and Girard has been an extremely important influence on my thinking. I discovered Peter Thiel—and his ideas, which later informed our book—through Girard, not vice versa.

During this time, I was doing a PhD in a quantitative group that specialized in predicting extreme events in complex systems. My supervisor, Didier Sornette, and the group developed models—guided by statistical mechanics and complexity—to predict financial bubbles and crashes based on imitation behavior. Given my background in philosophy and interest in mimetic theory, I’ve been probing the mimetic, sacrificial, and religious depths of financial markets for a while. That’s why we started to work on the paper that eventually became “Manias and Mimesis.”

We wanted to answer a central question: Why and how has progress stagnated, and what can we do about it?

Frontier: What inspired the idea for Boom? What is its genesis story?

TH: After we published that piece online, we wanted to take our collaboration to the next level, and I suggested writing a book on the causes of stagnation. Byrne and I had been obsessed with the nature of progress in general—and with questions concerning stagnation and decline in particular—for some time.

When I learned that Peter Thiel, Garry Kasparov, and Max Levchin planned to publish a book on precisely these questions but later abandoned the project, I suggested to Byrne that this was the most important non-existent book in existence—someone had to write it.

BH: We decided to write the book ourselves—a decision we came to regret a few times. In the initial stages, it became clear that we wanted to focus on bubbles as vehicles for technological acceleration and to flesh out the model of manias as drivers of technological progress.

Historically, bubbles are often dismissed as speculative or irrational phenomena, but we saw them differently—as accelerators of progress. Tobias’s previous work made us realize that bubbles could serve as a lens to examine stagnation not just economically but culturally. From there, it all escalated quickly.

Frontier: What key themes or questions did you aim to explore in the book?

BH: We wanted to answer a central question: Why and how has progress stagnated, and what can we do about it? But we didn’t want to stop at surface-level explanations.

An underlying theme for us was the dual nature of bubbles. They’re seen as destructive, but they’re also engines of progress. Think of the internet bubble or the dot-com era—these periods had significant spillover effects, driving technological and cultural advancements. We wanted to show how these cycles of boom and bust essentially function as engines for progress, not just in markets or tech but in science and society at large.

Bubbles are necessarily future-oriented, and nothing makes the future quite as visceral as realizing it’s where all your descendants will live. We worry that declining birth rates are both a sign and a predictor of people taking the future less seriously and being less motivated to build a better one.

Aging also creates a different political dynamic: the greater the share of the electorate composed of people who have already achieved reasonable success, the more policy debates focus on blunting risk rather than embracing an uncertain future. The more societies age, the fewer risks they take. This dynamic contributes to the societal risk aversion that we identify in the book as a key source of technological stagnation.

TH: In the book, we argue that bubbles—despite their volatility—often lead to infrastructural and technological advancements that outlast the bubbles themselves. Many economic bubbles, such as the railroad bubbles of the 1830s, 1840s, and 1880s, or the dot-com bubble of the 1990s, laid the foundations for the digital and industrial economy we rely on today.

Even more importantly, bubbles coordinate behavior—they signal that now is the time to build and that others are working on complementary projects. Intel wouldn’t have succeeded in making newer and better chips if the software industry hadn’t built products that demanded those chips, and the software industry would have collapsed without chips that continuously advanced.

Of course, while there’s a myriad of causes, a key source of stagnation that we identify is a shortage of agency and a collectivized form of risk aversion that infects most domains of tech and culture. It also raises deeper questions concerning a pervasive spiritual crisis of meaning.

In other words, stagnation and decline aren’t simply techno-economic problems to be solved technocratically—they’re fundamentally religious problems, rooted in the abandonment of transcendence. If the transcendent once served as our absolute source of meaning, its dissolution through secularization has left a profound void.

In other words, we can’t just colonize Mars; we also need to reconquer the soul.

Frontier: To get more practical, what was your writing process like? How did you collaborate?

TH: We divided the labor by chapters, each of us taking the lead on different sections. I focused more on architecting the overarching structure of the book and synthesizing the philosophical and theological ideas, while Byrne excelled at backing up and expanding on these more abstract speculations with concrete historical material.

BH: The process was intense. Writing with Tobias felt like merging two brains into an emerging new mind that wasn’t reducible to either of us. It was alienating at times because we were constantly questioning and revising, which dissolved the notion of clear authorship and provenance. Fortunately, our process involved lots of riffing on one another’s ideas (we needed outside editors to cut it down).

Frontier: Why did you choose Stripe Press as your publisher?

BH: When we drafted the first outline, I reached out to John Collison. In parallel, Tyler Cowen, who provided early feedback, mentioned the book to Patrick Collison.

TH: Yeah, we didn’t choose Stripe Press; they chose us. Stripe Press’s tagline, “Ideas for Progress,” captures the book/publisher fit best. They’ve built a reputation for publishing books that explore the intersection of technology, economics, and culture, so they’re highly aligned with our goals. Our book differs from other Stripe Press titles in that it transcends the technological and economic dimension and leans more heavily into philosophical and theological territory.

Frontier: Is this what makes Boom different?

TH: Of course, there’s other literature on the mechanics of bubbles and their positive role in developing and diffusing emerging tech. Various heterodox economic models claim that bubbles have net-positive externalities or spillover effects, but these models often remain “trapped” at a certain level of analysis—purely social, politico-economic, or historical (like Carlota Perez’s work).

Each theory offers important insights, but what’s often missing is the philosophical and theological dimension.

As mentioned, the motivating thesis is that we still live in an age of stagnation—if not outright decline—and haven’t seen enough techno-economic progress outside the world of atoms (to borrow Thiel’s phrase). While stagnation and decline are determined by many factors, a key source is risk aversion. We radicalize this claim by arguing that the root of risk aversion is ultimately spiritual/philosophical/theological—a crisis of meaning sparked by the collapse of the transcendent. We wanted to amplify this by weaving in philosophical and theological perspectives.

Our goal was to create something both timely and timeless, drawing on Nietzsche’s notion of untimely philosophy—writing for both the present and future. We wanted to challenge mainstream narratives while offering a deeper framework for thinking about progress.

Frontier: What do you hope readers take away from the book?

TH: At its core, Boom is engagement bait. The extensive footnotes shouldn’t obscure the fact that the book is ultimately an exhortation, written with urgency, to take more risks in every domain of life. Given the stakes, we need more risk-taking and agency. If even one person takes more risk with a high civilizational payoff, we’ll have succeeded. We can’t keep obsessing over the downsides without considering the extreme upsides—especially given that the West’s techno-cultural supremacy may be at stake.

Ultimately, the book is organized around paradoxical tensions generated by various conceptual dichotomies across different levels of analysis: the heroic individual versus the market-state dynamic, rationality versus irrationality, religiosity versus technology, emergent (positive feedback) versus top-down (negative feedback) systems, and so on.

We don’t pretend to solve these paradoxes—we offer no high-level policy blueprint or investment strategies. That might disappoint some readers, who might see it as a cop-out.

While we identify recurring and emerging macro-level threads, the conceptual model we develop affirms the singular or unrepeatable element as a driver of techno-economic and socio-cultural progress. Some may find it disappointing that, in the end, the book—and its argument—folds back into the individual.

In a deeper, existential sense, it’s a self-help book urging people to take more risks because the biggest risk we face as a civilization is not taking enough of them. In other words, Boom charts a very narrow path between techno-determinism and hyper-individualism—extreme visions of tech progress as either entirely automatic or completely random.

Frontier: What kind of impact do you hope the book will have?

TH: Since we constantly talk about taking risks, we had to assume some reputational risk ourselves. That’s why the book’s scope and aims might seem almost too ambitious. Ideally, Boom becomes a defining book of the early 21st century—one that captures and articulates the spirit of techno-optimism tempered by civilizational pessimism on the eve of emerging artificial intelligence.

BH: One risk of defining a period, of course, is that you end up summarizing the mistakes people were making at the time. The Great Illusion predicted the end of major conflicts half a decade before the First World War, for example. But that’s a risk worth taking!

Frontier: Can you share any key takeaways or practical insights from the book?

BH: A practical takeaway is the importance of embracing asymmetry. Bubbles thrive on information and perception gaps. Instead of fixating on risks, focus on the potential for outsized rewards.

TH: One of our main messages is that ambition—bordering on delusion—is an undervalued driver of civilizational progress. Believing in a future radically different from the present is crucial for breaking free from inertia. Progress often begins with someone willing to will into existence a future that ruptures the order of the listless present.

Frontier: What’s next for you both? Any future projects in the works?

TH: For now, we’re concentrating on the book launch and connecting with readers. We’ll also continue investing in frontier tech through our syndicate and formalizing our tech investing with a fund structure. We need to practice what we preach.