Venture investor Stephen Cole, Valar Atomic founder Isaiah Taylor, and Rainmaker founder Augustus Doricko (left to right) post up for breakfast at storied El Segundo standby Wendy's Place. Image: Isaac Simpson

Is SoCal’s radical technology scene memeing the future into being?

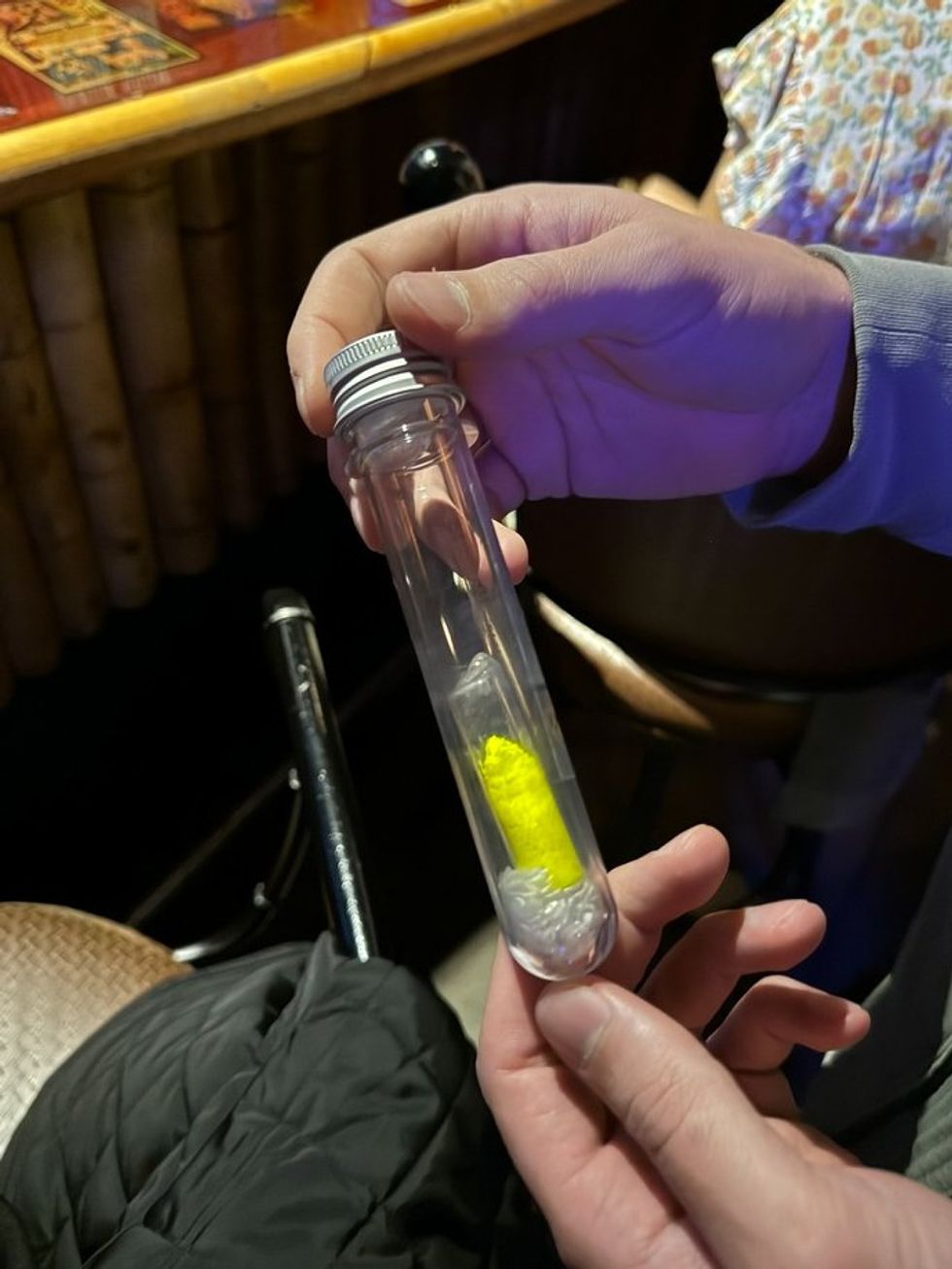

The hard tech renaissance of El Segundo. Purple Orchid, the bar of choice. A long, narrow, crowded shotgun space with vague Tiki aesthetics and a couple pool tables. 9 p.m. Thursday. One of the Gundo boys pulls a vial of plutonium out of his pocket. A couple fingers of yellow powder in a clear plastic tube.

“Holy shit,” I say.

“Yeah,” he says, his flat affect breaking into a conspiratorial smile.

“Is it dangerous?”

“Is it radioactive? Yes.”

“Then why are you carrying it around?”

“It’s only about as radioactive as several large pallets of bananas.”

The elevator pitches of its startups seem intentionally designed to make your eyes bug out: Manufacture Pharmaceuticals in Space! Build the World’s Largest Nuclear Plant to Synthesize Hydrocarbons!! Control the Weather!!!

“Are several large pallets of bananas dangerous?”

“Not really. But they are radioactive. It’s the potassium. Being around this much plutonium is effectively like working in the stock room of a Trader Joe’s.”

It’s a party trick and a genuine totem, not for luck, but to placate the thermodynamic god.

“Maximize extropy. Minimize entropy,” he explains. The world is constantly crumbling towards chaos. A little bit of plutonium reminds him that there’s something we can do about it. That doing something about it might just be the reason we’re here.

The Gundo scene parallels and is inspired by Effective Accelerationism, a Silicon Valley movement reacting against Effective Altruism. The right-coded Randian Effective Accelerationists, AKA e/acc, believe in taking the rails off technological development in stark contrast to the left-coded Utilitarian Effective Altruists, who want to exert total control over AI so it doesn’t turn us all into racist paperclips. E/acc and the Gundo scene worship at the altar of the Thermodynamic God, the omnipotent system governed by the laws of physics that determine the occurrences of life on Earth.

“The Thermodynamic God is a concept in Effective Accelerationism that refers to the idea that the universe is a vast, self-organizing system that is constantly evolving and becoming more complex,” tweeted e/acc leader Beff Jezos, approvingly quoting Google’s AI Bard (now Gemini). “This system is driven by the laws of thermodynamics, which state that energy can neither be created nor destroyed, but can only be transformed from one form to another. This means that the universe is constantly increasing in entropy, or disorder.”

The irony is that the Gundo boys both accept the power of the Thermodynamic God while being the people on earth most dedicated to overcoming its entropic power. The other irony is the Gundo boys over-index on Christianity. They worship both the thermodynamic god and the God god.

“When we started our companies, Augustus challenged me to see who could include more Bible verses in our pitches,” Isaiah Taylor, founder of Valar Atomics, told me. However, Cameron Schiller, one of the top El Segundo entrepreneurs, and founder of Rangeview, later tells me, “There’s two things that I don’t do that they all do. Christianity and cigarettes.”

Josh Steinman, X personality and El Segundo impresario, says, “the world is a definitive, malleable place, subject only to the laws of physics. People come to The Gundo because they don’t want their legacy to be moving decimal points around spreadsheets, or buttons around a computer screen. The future is simply waiting to be built, and it requires men of will to build it.”

A group of young outcasts, Silicon Valley defectors, and Apollonians—as a youthful Nietzsche called lovers of the sunlit dream of beautiful order—have sparked a genuine entrepreneurial movement. Perhaps moment is the better word here in the tony LA beach suburb of El Segundo. The specific neighborhood is called Smokey Hollow, I imagine because of the steam rising off the vast Chevron Refinery (formerly Standard Oil) since 1911, pumping out 300,000 barrels of crude per day. The steam reflects moonlight and sunlight, a silvery canopy over low buildings under a bleached-out sun, the feeling of being enclosed, isolated, and cut off from the rest of the city and the coast. Steel chimneys split every view. Even the beach feels industrial, metallic, “zoned for manufacturing”—repellant to the “lifestyle” beaches of Manhattan to the south and Playa Del Rey to the north—wind, rocks, giant tire tracks from the tractors that build berms when the surf gets high.

“The Scene” in El Segundo, called the Gundo, began only about two years ago. The elevator pitches of its startups seem intentionally designed to make your eyes bug out: Manufacture Pharmaceuticals in Space! Build the World’s Largest Nuclear Plant to Synthesize Hydrocarbons!! Control the Weather!!! A Substack titled the 2023 LA Hard Tech 50 serves as the almanac of the scene. Reading it, you’re amazed at its size and scope; so many brand-new, well-funded seed-through-E hard tech startups involving space, energy, defense, and futuristic materials are headquartered in El Segundo and nearby Torrance, just a bit inland. A Goldman Sachs report ballparked the number at 191 companies with $1.6 billion in investment, but even the guys on the ground aren’t sure. They think the “core scene,” which they mark to about 200 people, is probably significantly smaller.

The founders are handsome, fit, hard-working, and uniformly male. Their names—Isaiah Taylor, Augustus Doricko, Cameron Schiller, Soren Monroe-Anderson—evoke both an enlightened past and a techno-utopian future. I would imagine most of them believe in the theory of nominative determinism, that your name, at some level either metaphysical or natural, affects what you do with your life.

What’s most shocking is how young they are. The youngest and craziest by reputation, Soren Monroe-Anderson, is only 20 years old. A top drone racing pilot, he founded Neros Technologies, maker of ultra-low-cost war drones—“Keeping Humans Off the Battlefield”—which the United States has struggled to produce since outsourcing virtually all our consumer electronics to Asia. Like most Gundo boys, Soren has a premature revenge of the nerd’s vibe; these guys are a little too young and handsome to be this angry, yet conversations often turn to success as the best revenge.

Soren, also like most of the Gundo boys, doesn’t want to talk on the record. The exception to this rule is Augustus, founder of Rainmaker. Of the bunch, by far the most Dionysian—Nietzsche’s term for all spiritual lovers of intoxicating chaos—he has, in a way, become the face of the movement. He wants to make El Segundo the hard tech capital of the world and has a “fuck it” attitude towards to talking to the press.

He sees the Gundo as a response to a sclerotic American manufacturing sector that has lost all gravitas since the 1970s. “The Apollo program falling apart, the space shuttle program falling apart, fission and fusion research falling off, geoengineering and terraforming research falling off,” says Doricko. “People just lost the will to try to do great things like this.”

For this story, I spent time with three of them: Isaiah Taylor, founder of Valar Atomics, the nuclear and synthetic hydrocarbons startup; Augustus Doricko, founder of Rainmaker, the cloud seeding project; Cameron Schiller, founder of the more practical 3D-printed metals operation Rangeview. I also chatted with my friend Joshua Steinman, a Navy veteran and former member of the cyber security team in Trump’s National Security Council. Steinman, a well-known X personality, is considered the sort of Godfather of the Gundo scene—a connector and mentor for the young guys who can, at times, seem like they are in desperate need of a spiritual leader besides either of their gods.

“As Colonel John Boyd, father of the OODA-Loop used to say, ‘People, ideas, and hardware. In that order,’” Steinman told me. “Those who have come and are coming to El Segundo are the human capital that are going to build the future. They are going to build billion dollar industrial empires. It might be their current efforts, or future ones, but it will be them.”

The term Apollonian suggests gleaming metal. Rectangles. Sunshine. Elements of earth and fire. The essence of building and battle. I, a contemporaneously drunk gonzo writer and advertising man, am spectrumatically (yes, a word I’m making up, which is very Dionysian), Far Dionysian, the female to Apollo’s male (no homo). Liquid. Art. Sex. Drugs. There are fewer male Dionysians, but we have certain advantages.

Gundo’s idol Elon Musk is the ultimate Apollonian, which is evident because he can’t see the importance of Dionysian elements like “brands” and “design.” He mocks them in the intentionally sloppy branding of X and the deliberately hideous shape of the Cybertruck. There’s an anti-sexiness to Apollolians that they can either own, like Musk does, or worry about—for example, incel gamers who make spreadsheets of their attempts to get laid. The Gundo boys very much fall in the former camp. They’re definitely not incels, but they’ve forcefully eschewed that temptress, coolness. They do not give a fuck what you think of them. Compared to cripplingly anxious Silicon Valley, now full of DEI mandates and therapy-speak, it’s impossible to understate how incredibly refreshing and radical this is.

El Segundo is now and has always been Apollo’s place. There’s just something about the combination of sun, salt water, and largescale weapons of war. Top Gun makes even the most strident Dionysian nostalgic for something he’s never experienced. Part of the reason young builders have adopted El Segundo is nostalgic as well. John Northrop, as in Northrop Grumman, began manufacturing aircraft in El Segundo in the 1930s. It became one of the primary manufacturers of warplanes for the next four decades, and El Segundo became the place where oil and war met on the beach. Lockheed Martin, Boeing, and Northrop Grumman still touch El Segundo. Northrup sits next to the Los Angeles Air Force Base (now a Space Force Base), which it helped build. Douglas Aircraft eventually merged with Boeing, which, given Boeing’s recent competency failures, serves as a nice illustration of Gundo’s anti-mediocrity mission statement.

“The original company was McDonnell Douglas,” Isaiah Taylor tells me as we stroll along the pale, windy beach, stopping occasionally and often fruitlessly to light our cigarettes. “They made the MD-80z and the F-15 Eagle, the American workhorse fighter jet. The DC-10. 1960s through 1990s. Then they went totally Bugman. It was the MBAs that did it.”

I drove past LAX to the end of the Imperial Highway. As you approach the Beach Cities—Manhattan, Redondo, Hermosa, with El Segundo serving as the less desirable northern cap—Range Rovers and BMWs give way to Jeeps, Toyota trucks, and other signals of ruggedness. Off the highway, a large corporate office building reads “Cloud Team”; another is emblazoned with “Infineon.” This is the old corporate area where the offices of the big defense firms sit. But continue into the El Segundo proper, and you’ll find a strand of concrete running between the giant beachside oil refinery to your left and a little village of low, square, industrial buildings to your right. It is in this little stretch of five or six short blocks that the entire “El Segundo Startup Scene” lives. This is Smokey Hollow.

It also makes itself visible only on much smaller buildings on doors and banners: Cryofuture; FluidLogic; Rangeview; Arbor; Zuru. They have slogans like “Manufacturing the future” and “Tomorrow Reimagined.” Apollonians don’t put much stake in their naming conventions or copywriting.

More hidden are the defense-related companies, like Neros and the three other local drone companies, Epirus, Atmosphere Drones, and Soaring.ai, which, I imagine, take steps to remain invisible. So some say the Gundo buzz is all an elaborate DoD marketing ploy to draw white men back into the military before we go to war in Ukraine or the Middle East. After being there for two days, I can report that this perspective is nonsensical. They’re not hiding anything. I put the challenge to them, and the responses were always shrugged shoulders. What exactly do you want us to do? Not take millions of dollars from the government to build our companies? And as for the propaganda—yeah, we do want young, competent men to be interested in creating stuff for their country. And in defending it. That’s the whole point. Furthermore, El Segundo is not primarily a defense tech revolution but a hard tech revolution. Most of the people I met barely touched the DoD, if at all.

Later, a finance industry consultant who recently quit his job to join the Gundo movement tells me, “They’re taking on the Hobbesian leviathan and the government is paying for it.” They’re not shilling for war. They’re taking funding wherever they can get it.

There’s one coffee shop and one little brewery in Smokey Hollow’s forest of lowslung boxes. The rest of the bars and restaurants, including the Purple Orchid, populate a proper downtown about a mile away. Eleven a.m., Thursday, Smokey Hollow. I spill out of my own Toyota truck and let the sun beat down on me and the ocean air into my nose. The steam wafts high from the Chevron plant. An Asian man glares at me suspiciously out of a Tesla. It reminds me of a less beautiful version of Coronado Island, another sun, ocean, and fighter jets sort of beach town. In the restaurants in downtown El Segundo, you’ll see tanned middle-aged white men in tight graphic tees. But Smokey Hollow feels separate, younger, more radical. It recalls Hayden Tract, in Culver City, another minicity for young entrepreneurs also composed of low industrial buildings converted into startup HQs, albeit for Dionysian creative types, not Apollonian builders.

I walk into the coffee shop expecting sleek third-wave precision, but it’s your standard “community coffee” vibe k– dusty bean sacks, and a small roaster machine. There’s a statue of a penguin. Two chubby baristas in beanies. A couple of cholos lean over a computer. A record player sits unused in a cluttered rack. There’s an old man in the corner. On the wall is a painting of Rosy the Riveter holding a cattle gun. A woman below it designs a slide that says “Kant’s Critique of Reason.” Doesn’t feel particularly techy; more odd and random.

I post up on a couch, pull the industrial charging box hanging overhead on a pulley down to my level, and set the computer on a pillow on my lap. But then the old man in the corner—tanned, silver-haired, in his 60s— starts talking to me. He says he’s in tech, just moved back from China; has two kids at El Segundo High. He says he’s up at 4 a.m. watching a rocket launch in Dubai. He was an L1 blockchain founder, and now advises startups. He’s very excited about the scene in El Segundo, a big part of the reason he settled here. He asks me to message him on LinkedIn to grab a drink later. I can’t tell if he’s legit or a total kook.

The next morning, at breakfast at the diner, a Gundo tradition, I’m informed that this man tells tales. He’s a crazy person, an odd hanger-on. Augustus suggests that maybe he’s “the Straussian Diogenes of El Segundo,” one of several moments where I’m taken aback by how hyper-competent this 23-year-old is. The fact that this crazy old tech wanderer was the first person I encountered in El Segundo proves this place has a metaphysical pin. Two hundred young Apollos have manifested their own town drunk, a blind street preacher who greets newcomers with tales of hard-tech glory.

After camping at the coffee shop, I meet Isaiah and Augustus at lunch at a gastropubby Italian place. I bring a carton of Hestias as a peace offering. The Gundo smokes hard. Nicotine as nootropic. It’s treated like whiskey in Mad Men, the default activity for men to talk and ideate. I go on several long cigarette-filled walks through El Segundo and on the beach to absorb the vibes of the cohort, which I find to be a pleasant form of bonding albeit far inferior to drinking actual whiskey (again, we return to the distinction between the wet Dionysian and the dry Apollonian). I tell them I’m not here as a journalist—we all agree we hate journalists—but as a propagandist, which is how all journalists would introduce themselves if they were honest.

Augustus, 23, inhales a buttery green pasta dish. He sports a blond mullet, off-white sweats, and a cream Champion sweatshirt— it all goes well with his provocative swagger. Isaiah, 24, is more buttoned up. Quieter, more serious—his turquoise eyes betray total focus. Watching and evaluating, a sentinel keeping Augustus honest. There’s a third party at the lunch, an older and more typically tech-coded investor named Stephen Cole. Angel, preseed, and seed only. He smiles with genuine excitement as he describes finding the Gundo boys “via his own research.” Augustus explains that it’s not about becoming a unicorn but asserting God’s dominion over earth. Isaiah nods approvingly, staying intense. Stephen rides shotgun, having a blast.

I ask what the biggest threat to the future of the Gundo is. They all agree it’s from posers coming in and diluting the fertile ground they’ve worked so hard to cultivate. One of their favorite things to say is, “the Gundo isn’t zoned for SaaS,” meaning here, there’s no room for the typical tech bullshit that’s screwed up Silicon Valley.

“The biggest risk from our popularity is driving low quality startups in,” says Augutus. “In our group chats, there’s brutal scrutiny of each other’s technology. We’re well aware of Elizabeth Holmes.”

The Gundo smokes hard. Nicotine as nootropic. It’s treated like whiskey in Mad Men, the default activity for men.

They regale the Gundo practice of “office checks.” After the bars, they’ll drop in on each other to make sure they’re still working. “We police people who move here,” says Augustus. “If you’re not in office at 12:04 a.m. chugging white Monsters and popping Zyns, you deserve to get your funding cut.”

Austin failed to become a hard tech mecca because it takes 20 minutes to get anywhere. Here they’re all right next door to each other. “This is really a small town. We share technology. If you tear one of your drones, just drop by Cambium right next door, they’ll patch it right up.”

Augustus’ Rainmaker and Isaiah’s Valar Atomics split an unmarked office unit. It has a warehousey, under-construction sort of feel. A massive American Flag adorns one of the walls on the Valar Atomics side. It was visible during the Marc Andreesen-sponsored hackathon that drew eyes on X a few months ago. There’s also a bench press with a board showing high scores and a big sign with El Segundo’s motto: Where Big Ideas Take Off.

“All you need for hard tech is a Christmas tree, a bench press, and an American flag,” says Isaiah.

His Valar Atomics is easily the most ambitious project in the Gundo, if not in all of tech. He wants to synthesize hydrocarbons for lower cost energy. Essentially, oil as a renewable resource. But to do this, he also has to build the largest nuclear power plant in the history of the world.

He’s starting small by building his own technology for blasting CO2 into hydrocarbons, literally from scratch, starting with the most basic components you can imagine. I can’t say too much about it, but he showed me a nanoparticle catalyst, one of the strangest substances I’ve ever felt. A metallic gray “powder” that feels like a combination between wax and ash. After touching it, I can’t stop visualizing it seeping into the pores of my fingers, taking me over from the inside.

“Jet fuel is really just long chain hydrocarbon,” explains Isaiah. “But the chain gets too long, it becomes wax.” This catalyst should produce a hydrocarbon chain that’s just the right length to be used as oil-like energy fuel. Next door, the Rainmaker team focuses on cloud seeding—literally making it rain. His core customers are farmers in dry areas whose livelihoods depend on rainfall. The more of it, the better. Cloud seeding, however, has long been viewed as a “third rail” in weather science, both because it borders on the crackpot and because of the obvious climate implications. In reality, cloud seeding is not only possible, it’s been done effectively for decades. The issue, up until this point, has been measurement—there’s no practical way to measure its effectiveness, which has made it a very difficult pitch for investors and research institutions. But new research from the SNOWIE Project has finally been able to accurately attribute seeding success by measuring the reflection of rain formations from airplanes flying through storms.

“I wouldn’t have started the company if it weren’t for SNOWIE, because otherwise it’s just a third rail. The results haven’t been demonstrable for a long time, but because of that paper, it’s much more respected and appropriate.”

When you say cloud seeding, your mind imagines chemtrails, huge clouds of chemicals in the sky. It’s anything but. Augustus shows me the seeding injection drone and its related technology, which sit on a table in the corner of the open floor plan office next to a large steel sword. The injection mechanism, called an atomizer, is a tiny little thing, no bigger than your first. To seed a cloud, he tells me, all it takes is a really brave pilot with a handful of silver iodide.

Furthermore, there is “zero-sum cloud seeding” and “non-zero-sum cloud seeding.” In other words, sometimes, if you make it rain, that means somewhere else won’t get rain. Other times, you can make it rain, and it will have zero impact on rain elsewhere. Rainmaker is careful to only engage in the non-zero-sum practice.

Augustus and Isaiah are best friends from very different backgrounds. They met on X only a year ago. Isaiah is from an ultra-religious family in flyover country—a protestant branch with a based type of Calvinism (a telling analog to the highly deterministic Thermodynamic God). He was always an entrepreneur; he started an auto shop he still owns today. He dabbled in a few other startups, searching for something big enough to contain his vast ambition, an ambition, unlike that of your typical Silicon Valley-ite, based not on monetary success but on shaping a broken world in the name of God. Finally, he settled on nuclear. Augustus is from Stamford, Connecticut. A suburban kid. His parents are atheists. He went to Berkeley, became a frat boy, read Nietzsche and Camus. He got too into partying, hit rock bottom, and pulled himself out of it after reading Lamentations. He quotes Heisenberg: “when you start natural sciences you’re an atheist. When you go deep enough, you see God staring back.” He dropped out senior year and got involved in startups in Dallas. Now he and Isaiah go to the same church in Santa Clarita, a branch of the same one that Isaiah grew up with. Isaiah brought Augustus in.

After my long cigarette walks with Isaiah and then Augustus, we return sweaty and exhausted to their offices. I ask Augustus what he’s doing later. I’ll be in town for a couple days, I say; maybe we can grab a drink. He thinks about it, and at first his eyes light up, but then he catches himself, and gives me a cool smile.

“I’ll be working.”

Another Gundo idiom is that there are two types of founders, those who grew up playing grand strategy games, like Risk, and those who grew up playing first person shooters, like Doom. The former category are guys who like to think about the broad meaning of what they’re doing, how it impacts the world, and how to make broad-based political alliances. The latter category basically just wants to tinker. Isaiah and Augustus are grand strategy guys. Cam Schiller and Soren Monroe-Anderson are first person shooters.

Cam founded Rangeview, a 3D printer operation that he calls a cyber foundry. Basically, it makes really insanely intricate parts for both defense and corporate applications using hyper-advanced 3D printers that can print with metal. I visited him at his factory. He’s tall with fine features and a bushy head of brown hair. He’s more practical, no bullshit, and his business also seems much further along than the others. A team of 6–7 employees rotate shapes on CAD screens. They’re surrounded by various 3D printed objects, including a little bust of Teddy Roosevelt and other things I can’t mention. In a high-ceilinged warehouse room sits a ring of 3D printers and a row of giant kilns that look like the ghost containers from Ghostbusters. The 3D printers are one of the most genuinely futuristic things I’ve ever seen—a machine arm hangs over a sort of milky primordial metal sludge that looks straight out of the movie Alien, ready to manifest whatever CAD files are sent to it. The light is oddly orange, because the printers require that blue light be blocked out entirely. Besides the kilns, there are two huge American flags. They can’t use TikTok in the office, on orders from the DoD.

I tell them I’m not here as a journalist — we all agree we hate journalists — but as a propagandist, which is how all journalists would introduce themselves if they were honest.

Cam grew up doing Battle Bots. He was a star. Went to Harvard-Westlake, Class of 2018. His dad was an early adopter computer nerd, and his mom was an Olympian. Looking at this tall, strapping young lad, I’m reminded of the widely held African belief that you inherit your mind from your father and your body from your mother.

“Competitive robotics was my purpose in life,” he says. “All my friends were on the robotics team. All the social frustration I had went into that and lifting.” He talks frequently of this social frustration, which is odd, because he doesn’t seem weird. He seems confident, cool, and mature. A heartthrob in another life.

“The main problem I see is that people don’t want to build the small stuff,” he continues. “Manufacturing is the industry of responsibility, and aerospace is the highest.”

There are two standbys that you have to experience if you’re to say that you’ve visited the Gundo. One is “The Diner,” where the boys meet around 8 a.m. every morning. A beautiful little spot called Wendy’s. Red china. Watery coffee. Friendly waitresses who know everyone’s name. The morning sun gleams through the rectangle window just so. We’re all a little hungover, or at least it feels that way. Augustus, Isaiah, Soren, Cam, even the investor Stephen are all there, as well as kids who work for them who are somehow even younger than they are.

We cram into a booth that becomes a revolving door of people coming and going. “What hard problem are you working on today,” they ask each other. Other Gundo guys sit at the bar—I can tell because one of them is wearing a neon construction vest that reads “Builder Alert!”—but we don’t talk to them. Mostly, my boothmates are shy to talk on the record. They tell me they’re on a media lockdown since the hackathon got so much attention. They’re worried they’re becoming more about the publicity than the work. Cam addresses a pretty 40ish brunette waitress. “Diane, you never call or text me back!” She seems to adore the Gundo boys. Cam looks back to the table. “We love Diane.”

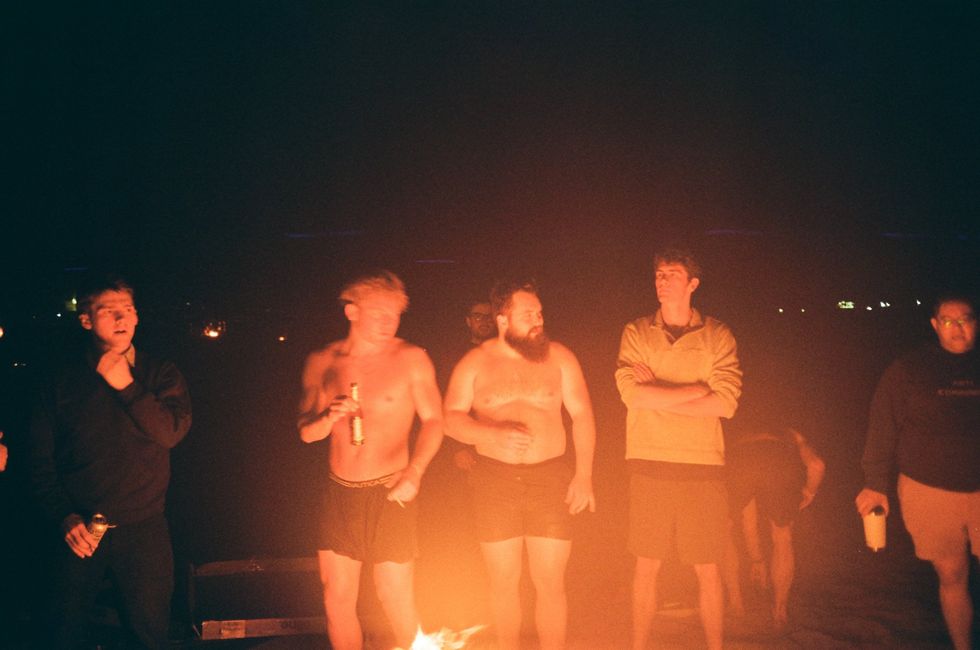

The other thing is the Friday night bonfire. In true Appollonian fashion, they frame it as wild and crazy. A place where they burn off all the excess—the unneeded furniture, packaging, and perhaps relationships tying them down. In reality, it’s contained in a dedicated fire pit in a long line of 40 fire pits on Dockweiler Beach. About 30 guys show up. Josh Steinman appears, presiding over the proceedings like a coach. They drink Casamigos and beers and smoke cigarettes. Augustus strips to his boxers and leads a cohort to jump in the water. All said, however, this is pretty tame. Mostly talking about building. Juicing each other up ... to work harder.

Hard tech, is it any better than soft tech? The word on the street here is yes, most definitely yes. These young men genuinely, completely, want to build stuff. Not stupid SaaS platforms to sell to fat middle-aged cat ladies at Deloitte. Actual real stuff you can touch with your hands, that you can fly in the sky, and yes, that kill people. What else is supposed to pay the bills around here? War is the father of all things, and the child is the father of the man. Young men like this make the world go round. They always have. Today, these young men feel snubbed by Silicon Valley, and the Regime at large. They’re Apollonians, remember, not douchebag bankers or stoned artists.

As the bonfire wound down, people said they were heading to Purple Orchid. This Dionysian was spent, in part from very a misguided attempt to walk to Dockweiler Beach from my hotel, which led me to a 1.5 hour journey alongside the seemingly endless “Butterfly Sanctuary” that serves as a buffer between the residential neighborhoods and nearby LAX. This area used to be full of houses, but when LAX expanded in the 1940s everyone was bought out and the entire neighborhood torn down, not to build the airport, but because they weren’t sure what would happen to people living under the direct path of the airlines.

So I ask for a ride from the aforementioned consultant, a young man defecting from the mainstream, he’s just bet his entire future on joining the Gundo scene. He’s got a math degree from Columbia. He’s wearing a denim collar under a cashmere sweater. Being with him makes me recall my time hanging out with finance dudes in Manhattan.

“Why so bullish?” I ask.

“I was being paid to fail,” he answers. “Instead of eating into these bullshit contracts from primes, we can do something else.” He’s referring to government prime contractors who receive “cost plus” contracts that incentivize vendors to eternally bill the taxpayer for mediocre, never-completed work. In the newly released Walter Isaacson biography of Elon Musk, you learn that one of Musk’s primary motivators for launching SpaceX was the absurdity of “cost plus” contracts. Everyone in the Gundo hates them too. “The system that’s being replaced is incredibly stupid. It’s remarkable to see it.” He saw it up close and got red pilled. “I didn’t understand the ecosystem at the time, God I was blessed. But then it dawned on me what was happening. It’s like realizing you were drowning while bleeding to death.”

Much is made these days of the problem of institutional rot. The Right blames the Left for allowing socialistic middle managers to come in and eliminate the rigid Apollonian drive towards excellence and for replacing it with a feminized routine of daily maintenance. Less is made, however, of how the exact same vacuum inheres in right-wing institutions. The same people take them over, and either we become Fox News or we get marginalized into a ghetto of purity spiraling. The only answer is El Segundo. It doesn’t wear its heart on its sleeve. It doesn’t need to tell you what it stands for. It doesn’t “scare the hoes.” It creates barriers to entry so high that nobody thinking about social or political issues can get over them. They wouldn’t be working hard enough.

Isaac Simpson is a writer and founder of WILL, a propaganda agency. He writes and podcasts at The Carousel on Substack and posts @Disgracedpropagandist.

Isaac Simpson