Julie Talbott

Art Bell was a radio performer who entertained a generation of people with American eccentricity and raw on-air talent. His particular brand of conspiracy and storytelling foretold much of our current discourse.

Memories of my childhood—and later, my adolescence—are mostly tied to the flicker of a CRT monitor. Most nights were all-nighters: playing MMOs, causing trouble in chat rooms (and later getting booted off AOL), watching ‘80s anime, and always, always listening to "Coast to Coast AM", which was also broadcast “worldwide” on the internet. I’d stay up long after midnight—1 a.m., 2 a.m., 3 a.m.—and sometimes until sunrise, when I should have been asleep, bracing for school in the morning.

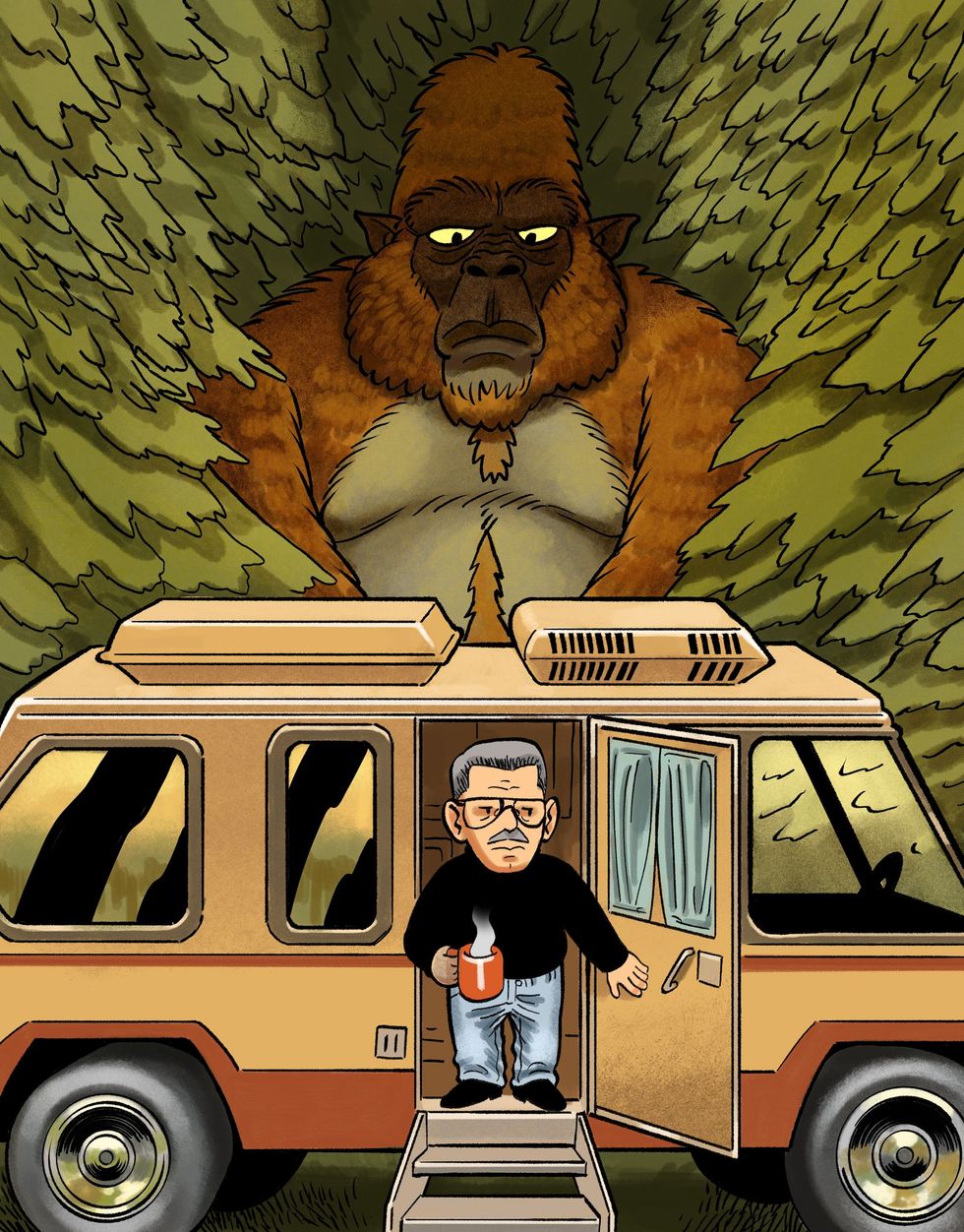

Predictably, there were many days I didn’t show up at all. It was the early 2000s, and my bedtime should have been 9 or 10 at the latest. I wasn’t a kid with a lot of stamina. There are kids who, miraculously, could pull all-nighters comfortably, but I wasn’t one of them. When you’re a kid, though, nighttime is a secret country. And for me, that country belonged to Art Bell, broad casting from a desert outpost in Pahrump, Nevada. His show, "Coast to Coast AM", was an entire universe unto itself. And in my otherwise quiet South Florida home, listening to him felt both rebellious and magical.

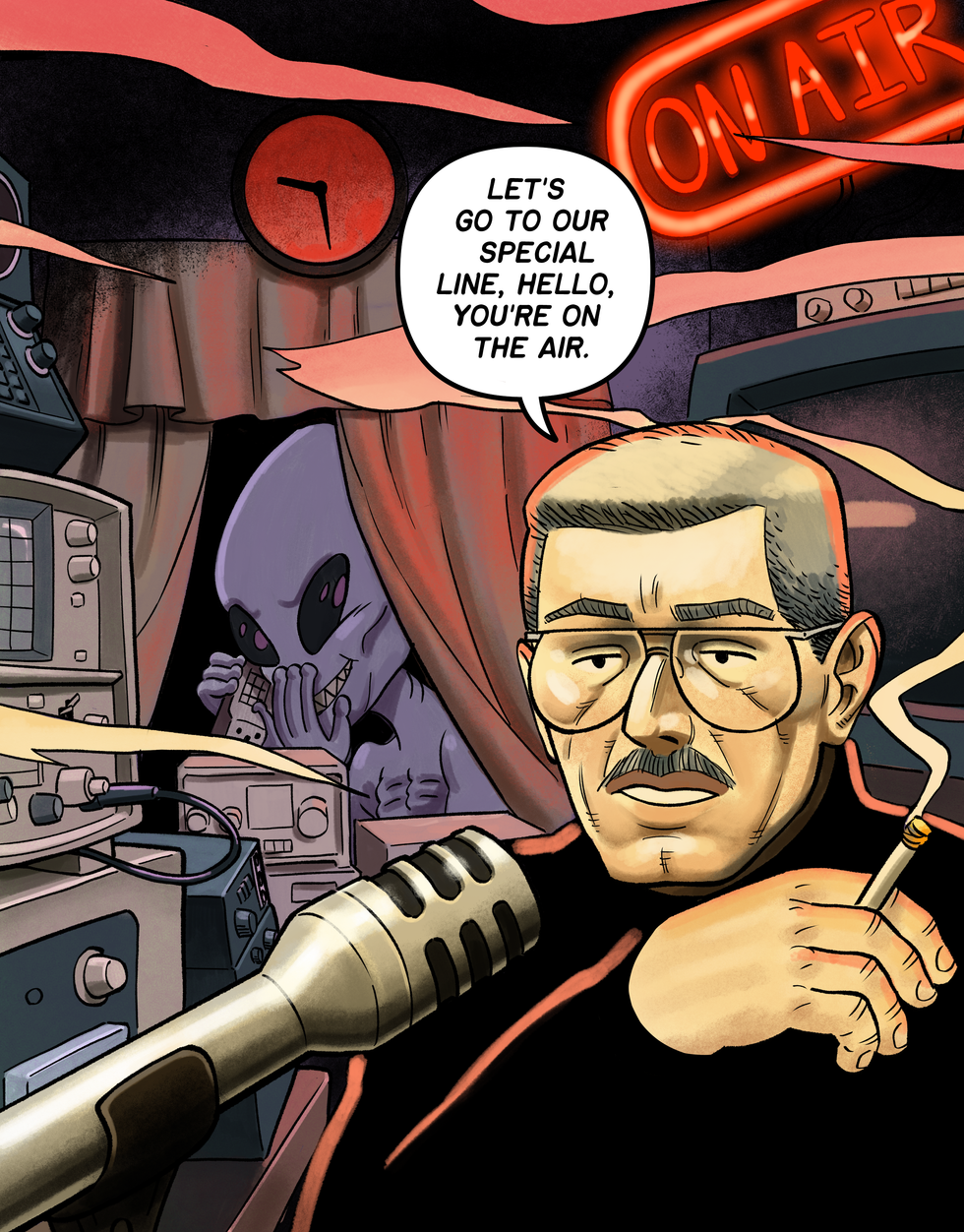

Bell was calm, faintly paternal, the eternal storyteller. Like a night watchman guiding me through the paranormal, Art Bell kept me company at night. He was Mr. Rogers for insomniacs who spoke of aliens and ghosts. The patron saint of being tired in European history or geometry.

A trucker on a lonely highway could dial in to share a UFO sighting. A bored night shift security guard might want to discuss a personal ghostly encounter.

To understand Art Bell’s hold on the imagination, though, you have to understand the show that made him famous: "Coast to Coast AM". Launched in the early 1990s and syndicated across the country, "Coast to Coast AM" quickly gathered a devoted audience. Not a cult audience, either. "Coast to Coast AM" was one of the biggest radio shows ever. The competition for late-night talk was slight, and plenty of people—security guards, long-distance truck drivers, people who simply stayed up late—were scanning the dials at 1 a.m., looking for something other than infomercials or angry preachers.

"Coast to Coast AM" wasn’t the first of its kind, but it was the best. It tackled esoteric and conspiratorial subjects—from UFO sightings and ghost stories to exorcisms in the Vatican. Even the show’s intro music, an ethereal instrumental that evoked a sort of late-night hypnosis, contributed to the ambiance of stepping into a secret world.

Few listeners were as enthralled by Bell’s show as Leah Prime, who began tuning in at nine years old. “I grew up listening to him on 810 WGY, which is a 50,000–watt boomer station out of upstate New York. They had originally had Joey Reynolds as the overnight radio talk show host.”

Then came the shift that charted her path. “I actually, at one point, I think literally when I was nine years old, called into the Joey Reynolds show. And then, like a flip of a switch a few weeks later, they switched over to Art Bell and "Coast to Coast AM". I would say unequivocally and without a doubt, that was the primary foundation of all of my media consumption, probably until college or even graduate school.”

She recalls his breadth of topics: “As the host of 'Coast to Coast AM', Art Bell covered a variety of subjects, ranging from the para normal to secret societies and conspiracy theories. He was also one of the most broadly syndicated radio hosts at the time. Over 500 stations were syndicating him overnight in the United States at the peak of the show. So every evening he was reaching tens of millions, maybe even hundreds of millions, of listeners in North America.”

For a child tuning in surreptitiously, that scale was nearly unimaginable. Leah describes late-night listening as both a thrill and a source of occasional terror. “And it would always be a test against time when I would record it to see where I’d actually get so scared, I’d have to turn it off. Because there’s something about listening at nighttime. He’d have ghost hunters on, conspiracy theorists on . . . Eventually, I’d reach a critical mass and have my bedside light on, just unable to keep going. Then I’d work up the courage to switch it back on and record more.”

“The first thing that made him special is that he had no call screeners. He was doing all the production. Nobody was pre-screening his calls. So anyone who called in, they were going straight and live onto the air. And if anyone’s ever listened to an old show, they will hear confused callers go, ‘Art, Art, am I on the air?’ And he’d be like, ‘Yes, you are on the air.’” That spontaneity reflected Bell’s interplay of skepticism and showman ship. “I think personally, he was a bit of a skeptic around a lot of the stuff that he was grandstanding, but he saw it basically as pure entertainment.”

This was revolutionary in the world of radio. Nearly all major call-in shows had (and still have) producers who vet each caller, someone who ensures whoever is dialing in isn’t nuts. Bell’s style, however, meant anything could happen. A trucker on a lonely highway could dial in to share a UFO sighting. A bored night shift security guard might want to discuss a personal ghostly encounter. A teenager could ask Bell to endorse him as class president— something that did happen on one episode in 2002. "Coast to Coast AM" was a live experiment in human eccentricity.

One effect of this approach was that callers often sounded genuinely startled to realize they were suddenly addressing millions of people and that they were truly on the air. You can hear that quaver in their voices on archived recordings. Bell’s calm and friendly manner disarmed them, coaxing them to share more. By the late 1990s and early 2000s, Bell’s popularity had surged.

“It’s funny, too, because even though he passed away in 2018, it feels like his legacy just kind of continues to grow,” Leah told me.

Art Bell’s career began modestly in Las Vegas, where his late-night radio show quickly gained traction, largely due to the scarcity of compelling overnight broadcasts. Its popularity soared, prompting Bell to relocate his entire operation to a secluded compound in Pahrump, Nevada, about 90 minutes from the Las Vegas Strip. From there, he hosted the show and managed every aspect of its production, cultivating an enthralling on-air atmosphere that resonated powerfully with listeners.

Many suspect he was more of a skeptic than he let on--though he was never dismissive. His job, after all, was to let people tell their stories.

Bell’s professional life was punctuated by multiple retirements and returns. He served as the program’s primary host until around 2003, interspersing his tenure with occasional hiatuses. Each time, he was drawn back to the microphone, solidifying his status as a fixture of late-night radio. Ultimately, in 2006 or 2007, Bell stepped away from full-time hosting altogether, passing the torch to George Noory.

I asked Leah to explain just who tuned into "Coast to Coast AM": “Everybody. Which is part of the magic of the show, right? I’ve talked to a number of different listeners and lifelong fans, and I’ve talked to everyone from overnight security guards to conspiracy theorists to amateur radio operators. His whole show blanketed the airwaves in the ’90s. So pretty much if you were scanning the radio on an AM dial anytime between 1991 and 2005, pretty good chances you were going to land on 'Coast to Coast AM'.”

Though the world has changed, a part of Bell’s spirit—his friendly tone, his open phone lines—remains.

In the 1990s, AM radio held significant sway. Bell shared the stage with talk giants like Rush Limbaugh, Dr. Laura Schlesinger, and Howard Stern. Bell was different, though: he’d question guests who spoke of time travel or UFOs but did so kindly, letting them lay out every last idea. "Coast to Coast AM" was, for many, a refuge for unusual theories—an invitation to wander outside the daytime boundaries of what people called “normal.”

One might draw parallels to today’s podcast boom, where hosts can spend hours on deep dives with guests in specialized fields. The difference is that "Coast to Coast AM" aired live each night, unfiltered, on stations across the country so entire swaths of the population received the same nightly show. That communal aspect, where millions simultaneously tuned in, gave the show a cultural heft that’s hard to replicate now in an age of fragmented, on-demand audio.

One longtime listener, John Steiger, referred to Bell’s audience as a “radio clan.” He read a written tribute out loud to me: “Arthur William Bell was a radio genius, a master of the medium, able to convey over the airwaves an unparalleled sense of belonging to the listening audience. Out of the dark ethereal art, his voice carrying through the night created us as a family.” He continues: “[He] brought us into being as his radio clan, so that over time, night after night, we came together instilled with the sense that we were no longer just our individual selves, that we were no longer hopelessly alone. We had each other. We had the show’s many varied and wonderful guests and callers, and most importantly, we had a leader in art, Art Bell.”

“It explains what Art Bell did for his audience, did for radio broadcasting, and meant to people,” he tells me. "Coast to Coast AM" was, in his view, a nightly gathering that redefined radio. Asked how he’d feel if Art Bell had never existed, he reaches for an unusual metaphor: “It’s like cancer, but if cancer were good. It’s taken over my life in the best possible way.” He imagines retiring to a brewery or a candy factory, transcribing Bell’s shows forever.

Steiger is indeed an unofficial archivist, who spends mornings transcribing episodes for his site, Art Bell Files. A single broadcast can last four or five hours. “Some people think I’m crazy,” he jokes, “but it’s not a chore. It’s a labor of love.”

In conversation, Steiger exudes the same mix of awe and devotion that so many fans seem to feel about Bell. For him, transcribing the episodes is a kind of personal mission, ensuring that the fleeting audio of Bell’s broadcast becomes a permanent record. Later, I’d find out that Steiger isn’t alone in his devotion—the Art Bell fandom is richer than even I knew. For instance, listeners would trade cassette tapes of particularly memorable "Coast to Coast AM" episodes—a practice reminiscent of “tape trading” in the Grateful Dead fandom. Over time, these tapes evolved into MP3 files, and entire online repositories popped up.

Bell has a special relationship with the internet and indeed, part of his impact was his early adoption of technology. By the mid-1990s, "Coast to Coast AM" had an online forum, and Bell posted updated webcam images of himself every 10 minutes, a novelty at the time. Dial-up modems whined, and the cost of being online was determined by the minute. Yet fans flocked to these new digital spaces to share rumors, dissect conspiracy theories, and coordinate meetups.

"Art was online so early that he helped drive a whole subculture to the internet," Leah tells me.

This synergy between old media (radio) and new media (the nascent internet) was a hallmark of his approach. He recognized that his late-night demographic included technologically curious types: hackers, ham radio enthusiasts, college students using the campus T1 line after hours. By hosting a bulletin board system (BBS) and then later an official website and a forum, he channeled that curiosity, fueling 24/7 discussions that often outlasted the nightly broadcast.

In many ways, "Coast to Coast AM" helped prefigure modern virtual communities— and it’s amazing that it’s seldom mentioned alongside other nascent virtual communities like the WELL. Bell stoked that synergy by reading emails on air, referencing forum threads, and encouraging listeners to send in faxes or images.

This might sound normal now, but in the 90s, it felt cutting-edge.

In a large audience, the line between make-believe and genuine belief can blur— or, in Bell’s case, the line between healthy engagement and toxic fandom. Some saw the bizarre topics as entertainment, while others sought evidence that these theories were true. The tension between open-minded curiosity and uncritical acceptance defined much of the late 1990s and early 2000s in fringe media.

Where did Bell himself stand on that spectrum? Many, like Leah, suspect he was more of a skeptic than he let on—though he was never dismissive. His job, after all, was to let people tell their stories.

“I think he took a fair approach,” Leah says. “He didn’t want to bully anyone, but he also asked challenging questions if the story seemed too outlandish. He was an entertain er, first and foremost, but he also respected the sense of wonder that his audience craved.”

Bell became adept at asking follow-up questions that teased out the contours of a claim—say, an alleged alien abduction or a time-traveling Jacob’s ladder, as was the case with the infamous Madman Markum— without outright endorsing or debunking it. Listeners, then, had the freedom to suspend disbelief if they wished. That approach endeared him to believers and skeptics alike, giving him a broad, “big-tent” kind of appeal.

One notorious example is the project known as Ong’s Hat, created by the self-described “internet kid” Joseph Matheny. The story circulated through zines, BBS, and eventually "Coast to Coast AM", detailing a remote corner of New Jersey’s Pine Barrens, where rogue scientists uncovered a device capable of crossing dimensions. Originally intended as a creative experiment, it became the subject of heated speculation once it was mentioned on air. Matheny subsequently encountered doxxing, break-ins, and threats from people convinced Ong’s Hat was real.

“If I had to do it over again, I wouldn’t do it,” he now admits.

Bell’s role was largely that of an open conduit.

“We have someone who claims to know about X,” he would say, then let the guest or caller take the stage. Listeners would be enthralled, then spill onto newsgroups and forums, chasing threads that stretched from speculation to certainty. For people like Joseph Matheny, that cascading effect became overwhelming as the boundary between a playful art project and a bona fide conspiracy eroded under the weight of collective obsession. It was a testament to the sheer gravitational pull of Bell’s microphone, an influence felt in ways both magical and tragic in equal measure.

Nowhere was that influence more chillingly apparent than in the case of Heaven’s Gate. The cult fixated on speculation about the Hale-Bopp comet, fueled in part by discussions on Coast to Coast AM and similar forums. Though Bell attempted to correct the record, emphasizing that certain alleged images of a mysterious “companion object” near the comet were fabricated, the group’s mass suicide in 1997 cast a long shadow over the subculture of conspiratorial radio. Bell publicly mourned the tragedy, insisting he had never intended to provide kindling for such an inferno.

Bell was no stranger to the weight of unintended consequences. Over the years, he “retired” multiple times, citing threats and personal turmoil. Some saw in these disappearances the hand of government pressure, a shadowy force unsettled by his show’s unflinching engagement with fringe beliefs. But the reality was both more mundane and more unnerving: it wasn’t federal agents that made Bell’s life unbearable, it was his own listeners. His fans.

Yet despite these darker episodes, his longtime fans remember the sense of warmth that his broadcasts conveyed. Even Matheny, disillusioned by the conspiracy scene, admits he still listens to Bell’s old shows as a security blanket.

That was the magic of "Coast to Coast AM". The calls could be unnerving or silly, but Bell always gave them space. He might challenge the details, but never in a way that humiliated a guest. Where other talk hosts were combative, Bell remained inquisitive. It was part curiosity and part showman ship, with just enough skepticism to keep listeners from floating off entirely.

If there is a single lesson in Bell’s decades of broadcasting, it’s that late-night radio offered a sanctuary to those who had nowhere else to air their strangest ideas.

Consider the simple act of driving alone on a remote highway at three in the morning. In a pre-smartphone era, your entertainment might be limited to cassettes or local stations with spotty signals. Suddenly, you stumble onto a voice discussing Bigfoot tracks or secret government labs. It’s a bonding moment; you realize hundreds of thousands (if not millions) are hearing the same thing. That sense of a shared, hidden community is powerful.

Bell’s show also soothed certain existential questions. If you believed in something beyond “consensus reality,” or if you suspected the government was hiding advanced technology, you weren’t alone. Others felt the same, and they phoned in to share and compare notes. This dynamic could be purely entertaining or dangerously confirmatory, depending on a listener’s state of mind. Bell walked the line by not being overly dogmatic.

He’d let someone claim they were from the future, then simply say, “All right, so how does that work?” leaving it up to the audience to decide.

It might be impossible to recreate what Art Bell achieved. In a society that cycles rapidly through news and commentary, perhaps we crave that midnight sense of possibility more than ever. And that may be Bell’s greatest gift: the notion that, for a few hours each night, we can step outside the usual bounds, pick up the phone, and hear a voice on the other end saying:

All right, that’s quite a story. Tell me more.

Katherine Dee is an Internet culture reporter. You can read her writing at default.blog and catch her on her pod cast, The Computer Room. This has been adapted from Katherine Dee’s audio documentary First Time Caller, produced by Taylor McMahon, with the help of Leah Prime, John Steiger, and Joseph Matheny.

Katherine Dee

Contributing Editor, Return