Bettman / Getty Images

Our nation turns its lonely eyes to space.

Men long for empty spaces. Why is a question that’s its own kind of desert, calling to a certain kind of soul, with answers that invisibly crowd the mind and thicken the air in our disincarnate digital age. “Space”—the vast blackness surrounding us in all directions—is the fixation of so many seeking emptiness in a world filled and overfilled, not just with objects but with the invisible artifacts of constant communication.

“My brain hurt like a warehouse, it had no room to spare / I had to cram so many things to store everything in there”: these words make up David Bowie’s moon-age lament in “Five Years,” the end-of-the-world anthem opening Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars. Today, as Jean Baudrillard showed so unsparingly thirty years after Ziggy, the world’s end, its filled limit, is experienced by networked man through the quantitative excess the virtual world makes possible. In cyberspace, the prospect of infinite content promises or compels us to max out our consciousness, our perception, our possibility. More and more are convinced, or act convinced, that Earth is obsolete, insufficient, used up. Now, only outer space provides adequate living space, the escape necessary for survival.

Here in Los Angeles, a city in the sluggish throes of being overtaken by the visible and invisible works of soulless technologization, billboards from the Foundation for a Better Life still dot boulevards with the youthful visage of longevity pro and sci-fi hero William Shatner. Against a blank black background, Shatner shares space with a composite of planet Earth and the abridged but ostensibly still inspirational motto, “BOLDLY GO.” It’s the title of his memoir, a tome stuffed with “reflections on a life of awe and wonder.”

In that book, the onscreen Captain Kirk recounts his recent real-life voyage on Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin craft beyond Earth’s atmosphere. “I love all the questions that have come to us over thousands of years of exploration and hypotheses,” he writes; “all of that has thrilled me for years ... but when I looked in the opposite direction, into space, there was no mystery, no majestic awe to behold ... all I saw was death. ...”

"I had thought that going into space would be the ultimate catharsis of that connection I had been looking for between all living things—that being up there would be the next beautiful step to understanding the harmony of the universe. ... It was among the strongest feelings of grief I have ever encountered. The contrast between the vicious coldness of space and the warm nurturing of Earth below filled me with overwhelming sadness. Every day, we are confronted with the knowledge of further destruction of Earth at our hands: the extinction of animal species, of flora and fauna ... things that took five billion years to evolve, and suddenly, we will never see them again because of the interference of mankind. It filled me with dread. My trip to space was supposed to be a celebration; instead, it felt like a funeral.”

Here in Los Angeles, a city in the sluggish throes of being overtaken by the visible and invisible works of soulless technologization, billboards from the Foundation for a Better Life still dot boulevards with the youthful visage of longevity pro and sci-fi hero William Shatner.

TMI, after all, at least for our overstuffed world’s purveyors of toxic positivity (propaganda).

Wistfully, Shatner notes that he later learned he was “not alone in this feeling” of a cosmic tomb—one promptly medicalized with a categorizable terminology, the Overview Effect, and observed routinely in astronauts, “including Yuri Gagarin, Michael Collins, Sally Ride, and many others.”

As the 2010s founder of a “spacegaze” band (Vast Asteroid, sonically located where American shoegaze and British space rock meet)—I had learned long before Shatner that space was the place to be haunted by our very darkest visions of meaningless doom. The blast of creative euphoria that pop music channeled in the years of America’s first moon missions—the age of the Whole Earth Catalog, which first embedded into Americans’ consciousness the abstract idol of the planet “seen from space”—swiftly gave way to a cold, brutal comedown.

In the 1980s, Bowie had become the eerie astral clown of “Ashes to Ashes,” Major Tom from “Space Oddity” now an embodiment of death in the interior void of drug addiction.

I’m hoping to kick but the planet it’s glowing

Ashes to ashes, funk to funky

We know Major Tom’s a junkie

Strung out in heaven’s high

Hitting an all-time low

Time and again I tell myself I’ll stay clean tonight

But the little green wheels are following me

Oh no, not again

I’m stuck with a valuable friend

By the mid-‘90s, Bowie’s personable cocaine fix had given way in the poetics of space to Failure’s inseparable heroin habit: “I gave up hope, in finding you / I’ve got a friend I’ve grown used to.” Failure completed the artistic transformation of the stars from a limitless canvas of vitalist fantasy to a metaphor for death’s intimate triumph in Fantastic Planet—a sprawling, harrowing space opera only surpassed by the crystalline dirges of Marilyn Manson’s work at the millennium’s end.

Manson’s Mechanical Animals and Holy Wood, with their dire warnings of sensory deprivation, alien worship, pharmaceutical slavery, surgical androgyny, and suicide as mass entertainment, summoned forth a vision of man’s “crucifixion in space” that neither Manson’s rabid fans nor his equally rabid critics dared truly to take to heart.

This is the sort of service to the human race Marshall McLuhan had in mind when he called artists—regardless of their content or quality—society’s “early warning systems.” The bracing speed with which the heavens slipped in popular music from a promised new paradise to a hellish outer darkness might have saved the American public from the vast delusions instilled by the late 20th century’s intergalactic blockbusters. But technology was moving most quickly of all, and under the spell of its master spiritual alchemists, America swiftly followed.

Technology, manifested as America’s superheroic savior in World War II and then the Cold War, made space supercool in the movies. Military prototypes directly inspired Star Wars archetypes, from DARPA’s Vader helmet to the X-wing pilot’s heads-up display. Cornerstones of America’s contemporary folk religion—the Rebel Alliance, the Force, the fragility of “home planets,” and the spiritual imperative to be galactic—arose from the global theater ideology of ultimate weaponry as ultimate entertainment.

Intriguingly, when the initially still more propagandistic Star Trek universe hit the creative wall of Gene Roddenberry’s relentlessly optimistic galactic spiritualism, Roddenberry pal Maurice Hurley revitalized the Next Generation series by introducing an antagonist, the Borg, that violated the cardinal Star Trek rule. Contra Gene, the Borg was a malevolent entity the Federation might never be able to defeat through the power of the high-tech human spirit.

The longing for empty spaces—the lure of the desert, not the void—is an answer to the perpetual call to purification, from all the distraction and delusion to which our senses and our passions, no matter how well-intentioned, always tempt us.

But today, techno-optimists characteristically hold out for celebration a grand synthesis worthy of Hegel: the Borg, but good, actually—a spacefaring race of cyborgs assimilating everything to ever more intelligent, ever more productive awesomeness. It’s a vision too big even for our virtualized, digitized, satellite-surrounded Earth, one forcibly liberated from God, nature, and our humanity itself. It’s an appealing picture even for relatively ordinary people, at least in America, where, with now-palpable desperation, we still associate off-planet activity with spiritually devout, biologically thriving, comfortably human strivers.

Perhaps that profile never accurately fit all of America or even the average American. But in the shared memory or imagination of those of us yearning to restore our greatness by recourse to the stars, it is a reality we can and should restore, if only through the power of acting the part.

“For use almost can change the stamp of nature,” as Hamlet memorably claims, and today, nothing promises to accelerate such change like the technology of simulation.

Dear Horatio, we might recall, offers a stark rejoinder in a different context, warning haunted Hamlet to not so boldly go where ghost and guilt might lead:

What if it tempt you toward the flood, my lord,

Or to the dreadful summit of the cliff

That beetles o’er his base into the sea,

And there assume some other horrible form,

Which might deprive your sovereignty of reason

And draw you into madness? think of it:

The very place puts toys of desperation,

Without more motive, into every brain

That looks so many fathoms to the sea

And hears it roar beneath.

Fans of space horror—from the Alien franchise, to The Thing, to the interstellar/interdimensional nightmares of Event Horizon or Clive Barker’s Hellraiser series—know that the military-industrial funplex that America’s civil religion became couldn’t stop our spiritual awareness of the dark side of space from penetrating the collective consciousness. But in today’s totalitarian environment, where software seems to have eaten the world’s living space and filled it with infinite information, accelerationist portrayals of the “lure of the void,” to use Nick Land’s terminology, present Hamlet’s temptation as the only way out of the spaceless, bricked-up prison that our virtualized world has become. The totalitarian state, lagging behind, strives to tag along: hurling ourselves into the void of space is just good actually—it’s patriotism; those who so much as press x to doubt are, per sovereign reason, traitors. Some now even say that, on top of all that, colonizing space, the planets, the stars is the Christian thing to do.

It’s all a bit disorienting for someone who, say, tried his hand at the Space Discourse almost a decade ago. As a somewhat youthful, somewhat known, somewhat bankable writer on his first tour in the author-industrial complex, I planned to make my second book an accessible plunge into the virtues of taking humanity out to nature’s frontier, and the vices of keeping us hidebound here on Earth. The slaved-over book proposal for Escape Velocity: The End of America’s Crisis and the Rebirth of Cosmic Destiny was rejected by every publisher my agent pitched it to. Fragments appeared online in the form of read-it-and-forget-it articles.

I was trying to locate a proper balance of humility and triumphalism: “Elon Musk isn’t religious enough to colonize Mars,” I argued at Foreign Policy in 2016. “Silicon Valley wants to explore space as tech entrepreneurs. We should be traveling as pilgrims.” Today I get chills looking back at the quotation I pulled for that essay from OpenAI’s Sam Altman, at that time no more than the head of Y Combinator:

“These phones already control us,” he told the New Yorker’s Tad Friend. “The merge has begun—and a merge is our best scenario. Any version without a merge will have conflict: we enslave the A.I. or it enslaves us. The full-on-crazy version of the merge is we get our brains uploaded into the cloud.” But this, Altman says, was the good part. “We need to level up humans, because our descendants will either conquer the galaxy or extinguish consciousness in the universe forever. What a time to be alive!”...

But there is another dream out there—a much older one, with even deeper resonances in society’s collective heart and soul.

This argument still holds up, I’d be tempted to say—but the ravenous Discourse has moved far beyond, riding off, as the joke goes, in all directions. For every nationalist Christian “case for” going multiplanetary, there’s a devout diatribe debunking space itself—a Satanic, Kabbalistic psyop denying the firmament above us and the flat earth below, God’s perfect cosmos inscribing us within perfect limits pending the dreadful Day of Judgment. In our hellacious virtual Eden where total information crowds out all possibility of misfortune, there is A Discourse for everything and One Discourse to rule them all. The space we long for is one last remaining place where, devoid of inescapable information, we can live in sacred silence and discover once again what can be heard, what can be lived, what can be grown at that ultimate frontier, where God meets us at the limit of our reach.

Billions feel deprived of the possibility of returning to this place, even if they do not know it at all.

In its uncanny absence of the frontier, the false presence of the void appears in the idolatry of space.

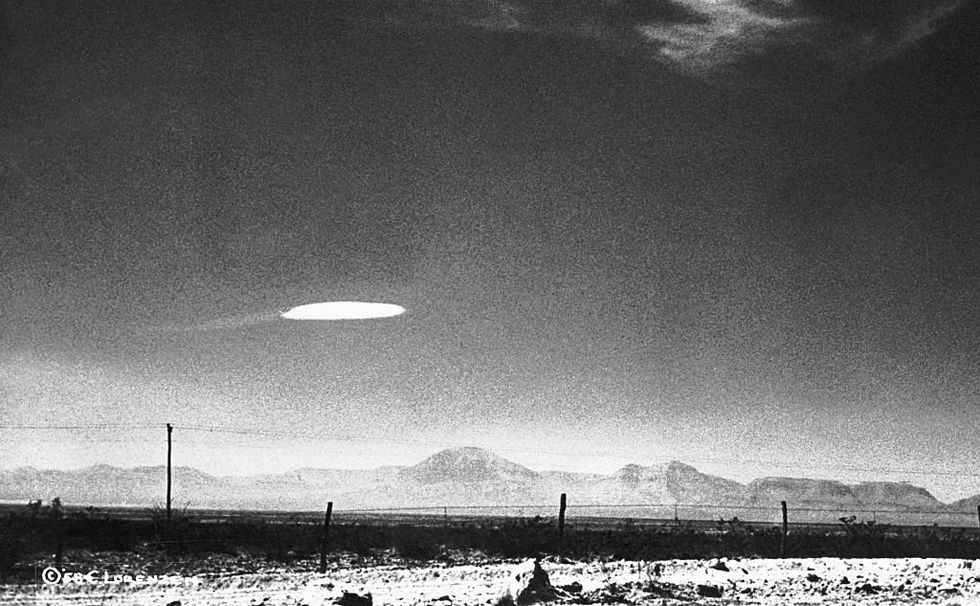

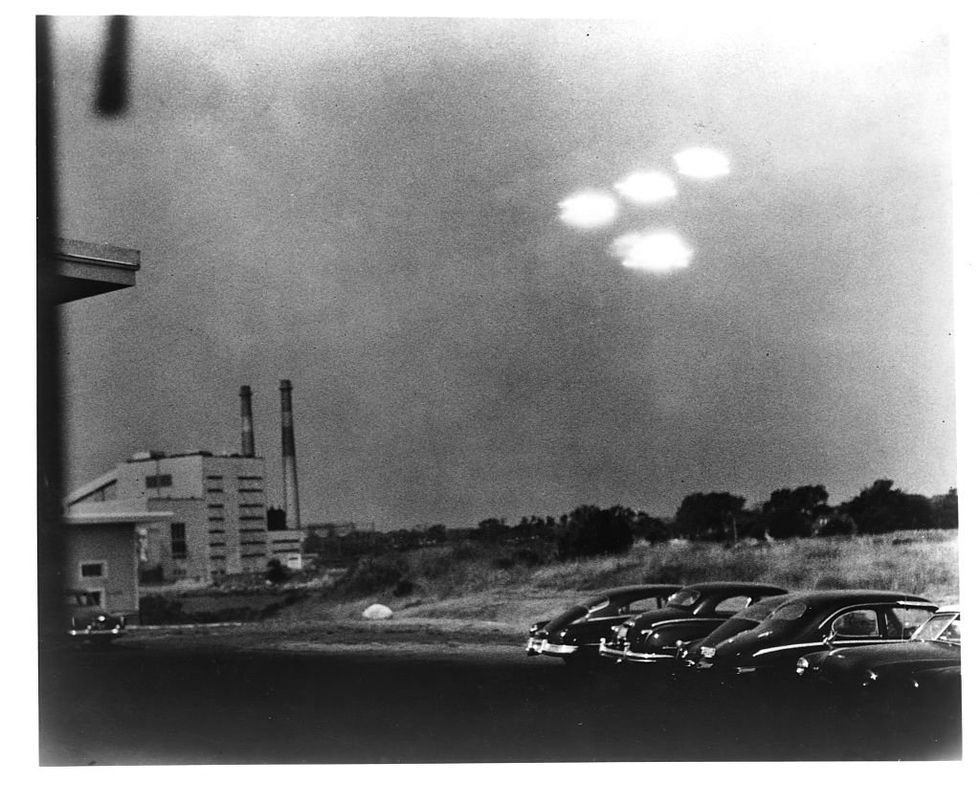

Space, as we know, is already dizzyingly full. Of galaxies telescopes reveal to be vastly closer to us than the science of logic and reason had once told us; of “dark matter” and quantum entanglements; of orbiting bots enclosing us in a second mechanical Earth; and, of course, of “aliens,” speculative, hypothesized, imagined, invoked, feared and worshiped. Space is full, but it is not conquered.

The Space Discourse, like the larger Omnidiscourse around it, expresses our desperation to toy with noise instead of confronting in silence what is revealed therein not to be a void at all but rather the very heart of reality, where the truth is disclosed about our relationship of love with the God who holds us to account for who we really are. Whatever else we may say about space, in our present spiritual condition, it holds out the glamorous, darkly glittering illusion that the void exists and is real. A genuine nothing—a blank we can accelerate into so as to disappear, to hide from God and his creation and all that we, in our fallenness, have over manufactured unto our disappointment, disillusionment, disgust, depression, and death.

There is no such void, no proper hiding place. It is even more artificial and far more unreal an escape than the first hiding place stitched together from fig leaves among the trees of Eden. How can we so much as begin to appraise the cosmos anew if we persist in such bitterness and desperation with the prideful machinations in our hearts, to try once again to conceal ourselves in their mysterious chambers from the Lord of All and His inescapable love?

The longing for empty spaces—the lure of the desert, not the void—is an answer to the perpetual call to purification, from all the distraction and delusion to which our senses and our passions, no matter how well-intentioned, always tempt us. By the measures of conquest and commerce, rockets and satellites remain an imperative; the Race for Space never ends; the soul calls out in anguish, seeking more living space in a universe overwhelmed by avatars, clones, and reflections of ourselves.

“I am more and more convinced that nothing, absolutely nothing is achieved or solved through discussions, arguments, debates,” wrote the theologian Alexander Schmemann in his diary entry for April 7, 1977. “Anything that convinces, or converts others, grows in solitude, in creative quiet, never in chatter. It does not mean that a creator should not have a universal vision—he must have. The error of our times is the belief in words, leading to their complete devaluation.”

Schmemann reminds us that we fill up the world with distractions above all about ourselves, about the naked simplicity of our utter failures apart from God: “one can always find helpful spiritual guides ready to solve problems, mainly by discussing them endlessly. The truth is much simpler: flesh and pride. They are the true keys to problems and difficulties, the root of endless discussion, of whispers during the dullest confessions, of all the introspection and morbid self-indulgence.” This relentless return to the eating of our spiritual tails, to the paralyzing act of tying ourselves into a knot, is what we find waiting for us in every hiding place—from the ends of the Earth to the ends of the universe. “Everything is fine, yet everything is wrong,” as Father Thomas Hopko puts it.

“In America,” Father Hopko goes on, “this is almost a national disease. It is covered over by frantic activity and endless running around. It is buried in activities and events. It is drowned out by television programs and games. But when the movement stops and the dial is turned off and everything is quiet ... then the dread sets in, and the meaninglessness of it all, and the boredom, and the fear.” Despite the promises, in many cases perhaps because of them, the simulated infinity of the internet has only exaggerated this ubiquitous condition. “Why is this so?” Father Hopko asks. “Because, the Church tells us, we are really not at home. We are in exile. We are alienated and estranged from our true country. We are not with God our Father in the land of the living. We are spiritually sick. And some of us are already dead.” Uncured of this spiritual sickness, even the greatest escape at the highest velocity will miss the mark of the future, bearing us back ceaselessly into the past.

There is only one exit from this world, and its portal is the human heart!

James Poulos is the Founder and Editorial Director of Frontier and Return at Blaze Media, and is the host of Zero Hour on BlazeTV. He is the author of Human Forever, The Art of Being Free, and the forthcoming Pink Police State.

James Poulos

BlazeTV Host