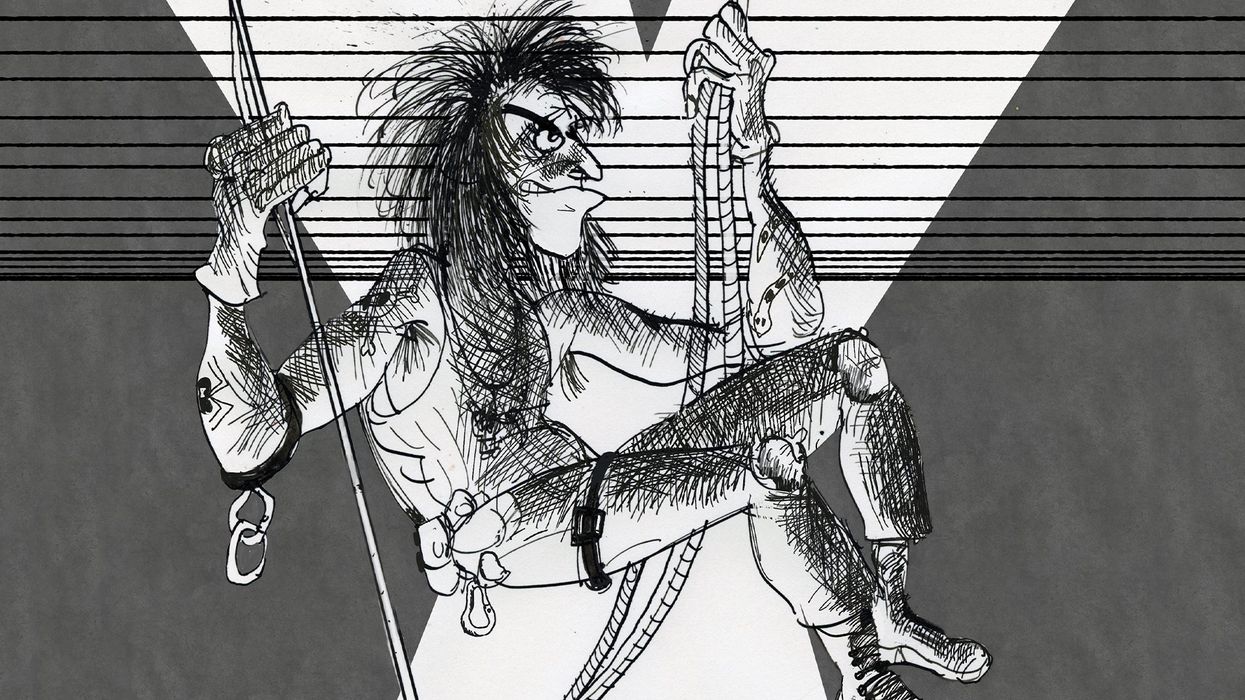

Gabriel Gigliotti

The bareknuckled ballad of a stagehand brawler.

Arena rigging, the process of hanging steel cables, kept my hands dirty and my mind clear.

I saw plenty of rock concerts and religious shows. I watched a hundred cage fighting matches. But that was all background noise while I played around in the venue’s giant jungle gym. I enjoyed the feel of wet chalk on my fingers as I marked the concrete floor. I savored that rough, dusty rope in my hands as I stood on an I-beam and pulled the motor chain a hundred feet into the air.

The process of pulling a point, which is securing a heavy metal chain to the ceiling suspension, is simple but elegant. A standard motor chain is one pound per foot, accumulating under your grip. Once the point’s up, you brake the rope over the beam. You attach the screw-pin shackle to the swedged wire rope. Sweat droplets fall into the void.

“Check point!”

Men shout back and forth from the rafters to the ground, confirming the motor is secure.

“Good!! Next—downstage left!”

Sick jokes and snarling insults echo across the steel grid. The tribes are held together by “atta boys” and firm handshakes. It’s chimpanzee politics within a larger superorganism.

Think of a massive concert rig hanging from the arena rafters—tons of lights, sound, and video held up by taut wire rope and a hundred motor chains. Imagine a bunch of dudes walking those beams above it. Try to picture the adrenaline junkies such a job might attract. For me, every gig was a meditation on our ape-like brains and ant-like social structure. I can still smell the beam dust and hot electric wires like it was yesterday.

My first show was over two decades ago at Thompson-Boling Arena in Knoxville. I was a smartass undergrad-turned-dumbass-stagehand, but I learned fast. As I pushed a wheeled road case from the loading dock to the arena floor, a ground rigger barked, “You see those ropes?”

I looked around and saw a half-dozen braided ropes coming down from the steel grid. Each was a different color.

“There’s a man on the other end of every one of those lines. So don’t pull the rope. Don’t touch the rope. Not ‘til you know what you’re doing.” The up-riggers danced across the beams a hundred feet overhead with no safety harnesses.

I pulled my first point a couple years later at the old Miami Arena. My instructor was Bobby Big-Eye, a fearless Midwestern towhead. His glassy orbs rolled in his skeletal face as if he wore a motorized Halloween mask. He breathed hard and laughed like a maniac. We stood side by side on a wide I-beam, 80 feet above the concrete floor. We were supposed to wear harnesses, but there was no safety line to attach them to, so it was pointless.

The Great Reset saw me transform into a proto-cyborg, along with billions of other people. Today, my new duties include logging onto the internet to complain about the infernal Machine.

Bobby Big-Eye showed me the art of pulling rope hand over hand, balancing on the beam’s edge, hauling up motor chains one by one. He showed me how to crouch and attach the gear. “Check point!” He ordered me to drop in my shiny new polypropylene rope, still slick and waxy. He watched as I pulled up the point. Then he disappeared to smoke crack on the catwalk, leaving me to my own devices. Eventually, more responsible mentors would give me proper training, but those early days were harrowing. One false move, and you’re dead. A lot of climbers fell in those days.

All this built character. It instilled a sense of duty. That’s why I beat the hell out of a reckless jerk on the arena floor. I had no choice. You never pull another man’s rope.

The fight happened in the main arena in Nashville. After cutting my teeth between Miami and Boston, I returned to Tennessee as a full-fledged rigger. By then, I could climb anything and was learning the math required to get a touring gig. Most of the fellas welcomed me into the tribe. Many of them were legends, or would be.

That original Nashville crew was still guided by the memory of Chief, a burly, charismatic rigger who’d been beaten to death with his own guitar.

One of his spiritual heirs was the Savage, who started a rigging company with his winnings from kickboxing tournaments. You also had Cro-Mag, who proved to be a hero when the outdoor stage collapsed in Indianapolis. While the rest of his crew cowered under the decks until the storm passed, Cro-Mag rescued victims from the wreckage. These were men I could respect.

But there’s always a hater or two, and this one dummy—we’ll call him Dead Weight—was always trying to dog me out. He did this to everybody. As a crew lead, he’d bully stagehands mercilessly. As a wannabe rigger, he tried to play the chief before ever proving himself as a brave. In truth, he never had what it takes to be either.

The tension built at a late load-out. Dead Weight was hitting on my female friend backstage as the band played on, and I came up to ward him off. For one thing, this chick only dated women. But even if she went for the XY, it wouldn’t be Dead Weight. So I told him to get lost. In response, Dead Weight pulled out his knife and started flicking it open and shut, staring at me with psycho eyes. I reminded him he was an idiot, and eventually, he backed down. But all night long, I kept thinking about that knife and that bugged-out stare.

Eventually, the blood boiled in my veins.

I was up high in the arena’s steel framework, with one foot on the I-beam, a thin horizontal steel bar, and the other on a fourinch metal bar used to maintain stability, called a spreader.

Dead Weight was 100 feet below, belligerent as usual. My safety line was tied to the wrong point on the ground. As I barked down at him to fix the problem, Dead Weight grabbed my rope, nearly yanking me off the beam. Although I was wearing a harness, it was just a painter’s one for appearances. A fall would have been ugly.

“Did you just pull my rope?”

I thought about attempted murder as I hopped off the beam and stormed across the catwalk. I thought about what I would say as the clunky service elevator took me downstairs.

All thought disappeared when I met Dead Weight on the floor. “I didn’t pull your rope!” he yelped, but it was too late.

Without hesitation, I hit him with a right jab and smashed his face with a hard left cross. I kept swinging as he fell back into a group of stagehands. People tried to grab me, but their efforts were half-hearted. The Christian crew was like, “Oh my Lord,” as I laid into Dead Weight again. He tried to escape, but I knocked him into some lighting racks. I bashed the back of his stubbled head before he got his legs and scrambled away.

The crew chief ran onto the floor and pulled me back. “Allen! Get out! You’re fired!” Half an hour later, the crew chief caught me again by the service elevator. “So, anyway,” he muttered, looking over his shoulder, “can you be back for the load-out?”

This is how things were done back then. In the end, justice was served tribal-style. Dead Weight never came back. After all, he did try to kill me. The reception was surreal when I walked into the loadout the next night. It was like I was in The Wizard of Oz. The stagehands basically gathered around singing, “Ding dong, the witch is dead, the wicked witch, the wicked witch... .” Dead Weight had bullied them all or tried to, and they were finally rid of him. Plus, they got to see him battered and humiliated on his way out.

For months afterward, I’d be at some gig or another, and someone would come up to thank me for giving Dead Weight what he deserved. In general, brute force is unprofessional at best and animalistic at worst. But as the gratitude kept coming, it was clear that sometimes a fist can right the world.

The experience steeled my nerves. I went on to rig shows across the planet. I became a top monkey in the touring Machine.

I fell for the harvest queen of Kansas City and destroyed it all in one night with a gorgeous Nashville lawyer. I climbed high steel with Asians, Euros, Mexicans, Aussies, Arabs, and Indonesians. I visited ancient Roman arenas, including the ruined Colosseum, where early riggers would hoist a massive canopy over the sunburnt crowd. During the decade I worked for the UFC, I got to watch cage fights night after night. I contemplated my humble place in the forest hierarchy. From Tennessee to Oregon, I taught rigging math to savvy rednecks and Cascadian socialists alike. I got sucker punched in jail. I scaled volcanoes. I paid my way through grad school. I hit the road again.

Then came COVID, and everything changed. I swapped my steel playground for a digital cage. The Great Reset saw me transform into a proto-cyborg, along with billions of other people. Today, my new duties include logging onto the internet to complain about the infernal Machine. Now and again, people ask if I’ll ever go back to riggin’. With a wry grin, I tell them, “I remember it fondly.” You couldn’t pay me to go back—well, you’d have to pay a lot—but truth be told, a grid monkey feels most alive in the jungle.

Joe Allen is the author of Dark Aeon: Transhumanism and the War Against Humanity.