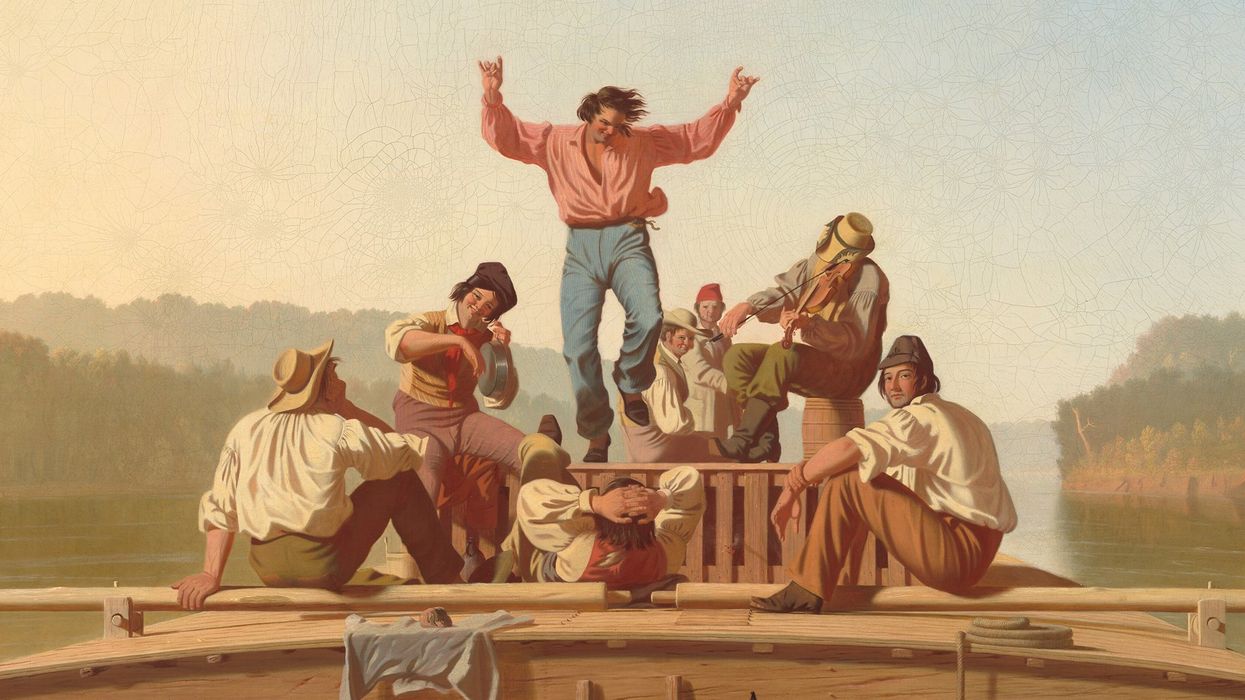

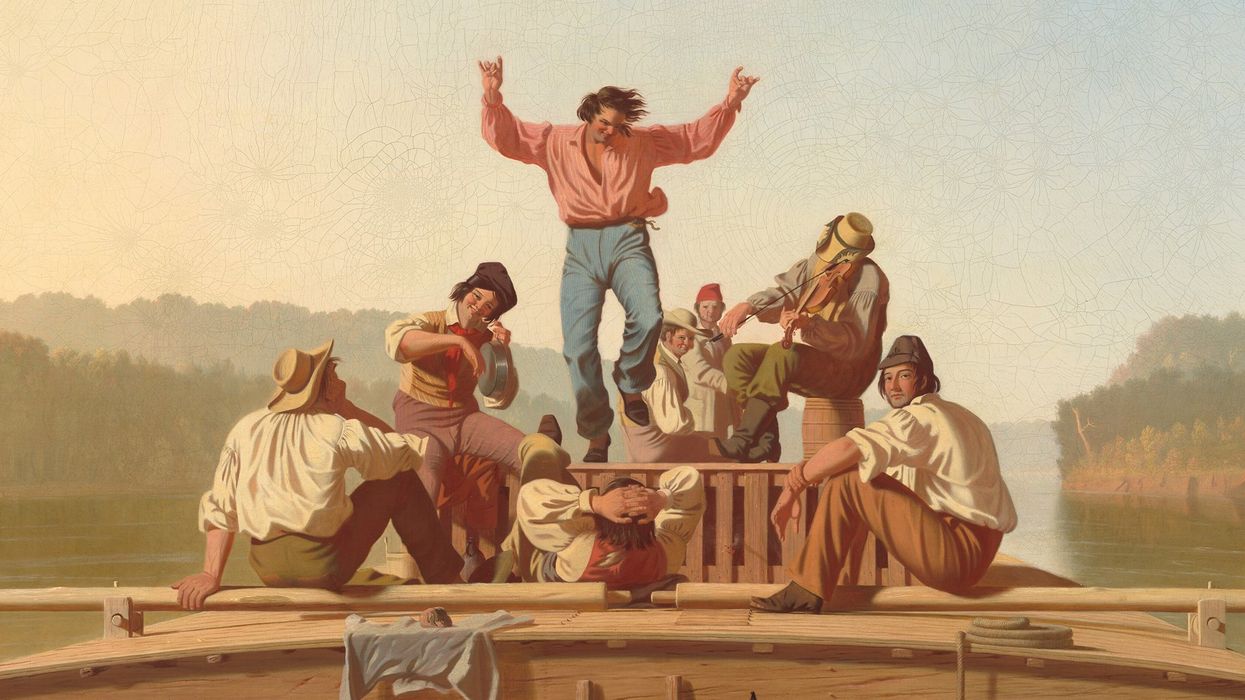

George Caleb Bingham: The Jolly Flatboatmen (1846) | National Gallery of Art

How to put the life back into our way of life.

This magazine aims to help you discover new frontiers and highlights people who are already exploring and building within them.

We live in a country that governs as though the frontier were long dead. A bureaucratic mindset, burdensome rules and regulations, “expert” control, and woke capital and its oppressive ideology constrain the thoughts and actions of millions of Americans. Our fenced-in culture rehashes the same tired themes with diminishing impact, while strictly policing anything created outside its boundaries.

We write for those who hold out the possibility that, in the sound of the winds blowing through the trees in the canyon, the waters flowing over rock, no less than the stillness of the desert itself, we might yet hear the voice of God.

The result is that people of all kinds and from all walks of life feel today as if there is no remaining space in their lives left open to conquer, explore, and build within. And if such a thing exists somewhere, they feel they are prevented from finding it. There may be no wall preventing people from across the world from entering America, but there are many walls that seem to block Americans themselves from finding new and better ways of life in the 21st century within their own country.

Yet we are still Americans, and the frontier is always with us, if only in our hearts and minds. Many yearn for it, and some search for it still. Throughout the nation, there is a commercial-cultural movement of visionaries and builders alike who have found new frontiers and are creating and working freely within them. And a related return is now underway in search of deeper wisdom, as well as spiritual sustenance. This movement doesn’t yet have a name, and our media and institutions are hiding it from view.

Frontier exists to show it to you.

There’s a reason it’s hidden. Established orders don’t want you to see this rising tide for what it is, and they want to keep selling you the same ideas and products, in the same rickety old framework, and maintain their position. But men like “Buffalo Bill” Cody both made the frontier and told (and sold) its story simultaneously. This is the American way.

We exist to tell it—and inspire you to make it.

The most famous American historian of the frontier, Frederick Jackson Turner, wrote that “frontier” once meant, “in general, the boundary that separates contiguous states.” The analog in nature is where the field meets the forest, or the ocean meets the sand. The word’s etymology points back to the front or face of a person that is not a façade but simply reveals him. In Europe, a frontier was a line, a nation’s front-facing border, or outer limit, of a nation.

But Turner, in his 1899 entry for “Frontier” in Johnson’s Cyclopedia, also wrote that “in a more restricted sense, employed especially in the U. S.”, ‘frontier’ meant something different. In America, the frontier was not a line, but a space. A space beyond official borderlines. Not an empty space, but one defined by the geographic landscapes of America and the peoples who roamed across them.

More specifically, the frontier was an area that was not yet settled: “In the reports of the U.S. census the frontier-line has been defined as the inland line limiting the area which has an average, county by county, of two or more inhabitants to the square mile. This area is called the settled area.” These sparse territories were not the frontier, exactly, but expanded behind it.

As Turner put it, “Between this census frontier-line and the Indian country the belt of territory sparsely occupied by Indian traders, hunters, miners, ranchmen, backwoodsmen, and adventurers of all sorts, constitutes the traditional frontier.” In America, the frontier referred to the “outlying regions which at different stages of the country’s development have been but imperfectly settled, and have constituted the meeting-ground of savagery and civilization”; the frontier was on “the outskirts of civilization, the regions but partially reclaimed from savagery by the pioneer.”

The American frontier was not a mere boundary but a place, not a line but a region. And this notion of frontier came to define what America was for the entire world.

In the 1700s, George Washington was internationally known for his early exploits on the frontier. However, he became the greatest American of the century because he answered the unsettled question of governance in America, fathering a nation that would long outlast him.

In the 1800s, William “Buffalo Bill” Cody, gained notoriety for his early exploits settling the unsettled West. He became the most famous American in the world owing to his traveling show, which revealed that frontier to the world, inspiring a century of mass media depictions long after he died.

That Western American frontier of a certain time and place is gone. But it is this region, this kind of place, that we desperately need to find within ourselves and within our nation once again.

What is at stake in the region of any frontier is this question: Who will ultimately settle and shape it, and how?

Just outside the “settled areas” of habit and experience within ourselves, we each find “the meeting-ground of savagery and civilization.” This, too, is never an empty space: its contours arise from our human nature, our specific personality, and where and how we live our lives. Like any geographic frontier, this space within is neither good nor bad of its own accord, but the cutting-edge potential and never-ending battle within us to explore, build, and develop ourselves—or devolve into addiction, vice, and evil.

We cannot find this inner frontier when we are habituated to self-harm and then self-medication to numb the results, immersed in screens, hypnotizing ourselves into slumber rather than exploring, confronting, conquering, and building in the very real frontier within ourselves. But as Marshall McLuhan once said, “’Numbed to death by booze and tranquilizers’ is an average strategy for ‘keeping in touch’ with a runaway world.”

If we don’t escape the screens and find an inner frontier, we can’t question the distortions within us. As unthinking products of our environment and civilization, we don’t own or control ourselves and can’t reshape ourselves for the better. As McLuhan also said:

Since in any situation 10 percent of the events cause 90 percent, we ignore the 10 percent and are stunned by the 90 percent. Without an anti-environment, all environments are invisible. The role of the artist is to create anti-environments as a means of perception and adjustment.

In other words, like the proverbial fish, we can’t see the water we are swimming in if we don’t get out of it from time to time. Great artists, leaders, and visionaries strain to do this in both healthy and destructive ways. They explore and inhabit unsettled territory and, in so doing, are sometimes able to look clearly at their society and its way of life and critique it with fresh eyes.

All human beings who seek fulfilling lives need to do the same from time to time. If they

cannot, they wither and eventually long for death. The desire for an “anti-environment” can lead us into darkness or into the light. The desire for emptiness and silence amidst the noise must not devolve into a retreat from reality into nothingness, into nihilism, or Western civilization’s increasing desire for suicide. As James Poulos explains in “Freakout at the Final Frontier,” “There is no such void, no proper hiding place. It is even more artificial and far more unreal an escape than the first hiding place stitched together from fig leaves among the trees of Eden.”

But each of us needs silence still—to grow and shape ourselves we need purposeful time in the wilderness, and we depend on leaders who have spent time being formed there. The most complete natural wilderness is the desert, where Christ was tempted, and the Desert Fathers made their home. The sea and the space between the planets and stars are similar. Here all other aspects of life fade away. In the wilderness, you battle and shape yourself.

As Poulos writes, “The longing for empty spaces—the lure of the desert, not the void—is an answer to the perpetual call to purification, from all the distraction and delusion to which our senses and our passions, no matter how well-intentioned, always tempt us.” But this is purifying precisely because isolation is not natural to us. While we rightly desire purification for its own sake, as we desire our own happiness, we also need that purification in order to build a better human society and to better live within it.

The time of decline in which we live requires refounding and rebuilding. It is only on the frontier that we can not only radically reconsider how we live but also begin to live differently. The frontier is not simply a wilderness; it is a space to recreate and reform our civilization.

In part, this is because of necessity. To live in an actual, geographic frontier outside of civilization requires us to pay closer attention to how we obtain the basic necessities of life, which means paying more attention to the natural world and its rhythms. Similarly, if we can find space to question the way of life we each live now without thinking and by default—as defined for us by the rest of society and culture—we are suddenly forced to confront ourselves and our own human nature.

But the frontier also enables us to experiment, to build differently, and to correct mistakes and wrong turns long since made by settlements and established cities. We live by habit, and move within the paths, streets, and highways that custom and the architecture of civilization have built up over the centuries. If the ancient city has built wrongly somewhere along the line, and for many years, it seems impossible to change.

We write for those who refuse to accept incompetence and decay and still seek excellence—who seek work and love alike with meaning and higher purpose.

But this is not so on the frontier. Here, one can look back on civilization and bypass any stifling layers built on wrong turns. For while savagery may meet civilization on the frontier, all civilizations decay and descend into refined savagery over time, while praising the descent into savagery as progress. Adjacent to civilization, the frontier allows its inhabitants to rethink principles and purposes, and to reconceive how things might be done best. We bring our habits and knowledge from civilization and are free to reapply them and channel what’s good, drop what’s bad, and attempt to develop new and better models of living.

And it is this frontier that we are still interested in finding and settling in the 21st century. Our survival may depend upon it.

On the frontier you will find grifters, losers, criminals, and con men, along with many others who are not comfortable or successful in “civilized” society. But you will also find visionaries, builders, missionaries, and individuals and families seeking a better way of life. You will find new institutions, new ways of doing things, new ways to live well.

Those who thrive on the frontier disagree—often radically—about the vision for the future they are working towards. In fact, these disagreements are often the ones that matter most, and are much more salient than the stale old disputes among people droning on in “normal” society. This is to say that the people and the movements we highlight for you here will often not agree, and we may not agree with them, or even among ourselves.

For instance, Chris Rufo and Matt Taibbi do not agree on politics, but both dissent from settled opinion. In order to pioneer new thought and action, one must first get past the obstacles now in our way.

In, “ Behind the Twitter Files,” Taibbi describes what led to the historic series of Twitter threads published after Elon Musk’s purchase of the social media platform. “At the end of that first day my head was spinning. What had been a relatively minor story about Twitter’s private censorship of a New York Post report on Hunter Biden’s laptop now looked like it might be of major, even historic importance, and involve a range of government agencies.”

The Twitter Files would go on to reveal the extent of censorship and control the federal government was exercising on legacy media. Twitter, subsequently transformed into X, is now one of the only remaining free speech frontiers in media, with profound effects on the national elections and other matters of great importance in this volatile and historic year.

In Peter Gietl’s interview of Rufo (“The Godfather”) after his successful effort to fire the president of Harvard University for plagiarism, Gietl reveals a model of a man attacking the most powerful institutions in America from outside the settled areas while also rebuilding alternatives. It is perhaps no coincidence that Rufo spent five years documenting people’s lives in the forgotten cities of Youngstown, Ohio, Memphis, Tennessee, and Stockton, California, and says “I have learned more from the streets than in any classroom.”

On the frontier, those who are truly successful and build well carry with them deeper purposes from civilizations gone wrong, and they often seek to save their history and ideals from destruction. This is the difference, as Glenn Beck explains, between the success of the Plymouth colony and the failure of Jamestown. While many know Beck as a “media figure,” fewer understand that he is a man on a mission to save the American story, which means preserving our historic artifacts from civilizational decline, come what may. Any righteous settlement of the future will require saving the past from present destruction:

The story is who we are. Our story is being destroyed right now, being rewritten in real-time. We must paint, film, learn to tell, and collect the story of America.

The freshness one encounters when entering unsettled areas often makes a return to something older, deeper, and higher possible. The American frontier was and still is a place where one can look directly into the great cathedral of nature, as Katarina Bradford reminds us the great American conservationist John Muir once did: “Muir was, first and foremost, a man driven by the sacred.”

But the spirit of the frontier allows us to look directly into our human nature. Against the rising “Cyborg Theocracy,” our technological advancement gone awry, Mary Harrington works back, in her article “ Cannibalizing Feminism,” through our basic understandings of men, women, sexuality, and our own happiness. In “Anti-Natalism and the Impossibility of Consent," Emma Waters chooses life and rediscovers the gift of life and family that must be sought for itself, as simply good, rather than for the sake of GDP and the stuff of white papers. And Josh Centers points to his own modern family’s turn back towards ancient wisdom, ever new, and the divine in “Take Me to Church.”

At the same time, the frontier requires an appreciation that “developed” societies lose for the hard work that makes them possible.

Mark Levin tells us how he “learned to admire people who work hard, and who work with their hands,” who are “among the most important people in supporting our way of life”– that is, “the people who make America work.” These are the forgotten people whose virtues that are now essential to respect and recover if we are to build anew. In “Blue Collar Blues,” Joe Allen, now writing for a living, recounts what he learned while engaged in such work. In the aftermath of a hurricane, Auron MacIntyre rethinks our “learned helplessness” to take basic care of ourselves and our families, and the necessity of developing tight-knit local communities.

Yet we also are in desperate need of innovation and new enterprises. Underneath the tottering edifice of California, now a one-party state that people and businesses are exiting by the year, Isaac Simpson finds the driven young men who are building the bold companies of the future. From literally making rain and fire (in this case, plentiful and inexpensive nuclear power), their startups aim to compete against the bloated, corrupt prime contractors that hose up billions annually from the federal government: “these guys are a little too young and handsome to be this angry, yet conversations often turn to success as the best revenge.”

Finally, in the midst of all our current political madness, there is also a renaissance in recreation: new poetry ( McLuhan, Yarvin), new TV shows (Dusty Bluffs), new video games (Prudentialist), a new return to fitness (photo essay), new food (Rhinehart) that nourishes us, new spirits (bourbon review) that soothe our own, and a new consideration of the best places to drink them (Bedford).

Volatility will increase in America. But we write for all those who seek truth, goodness, and beauty, regardless.

We write for all those who dissent, who question The Narrative and The Discourse and the systems of control that created them.

We write for those who refuse to accept incompetence and decay and still seek excellence—who seek work and love alike with meaning and higher purpose.

We write for those who still love the human and seek to perpetuate and enrich humanity rather than snuff it out.

We write for all those who simply want to find and live a better way of life.

We write for those who hold out the possibility that, in the sound of the winds blowing through the trees in the canyon, the waters flowing over rock, no less than the stillness of the desert itself, we might yet hear the voice of God.

You are not alone. We are not alone. Welcome to Frontier.

Matthew J. Peterson is Editor in Chief of Blaze Media.

Matthew Peterson

Former Editor in Chief