ROBERTO SCHMIDT / Contributor | Getty Images

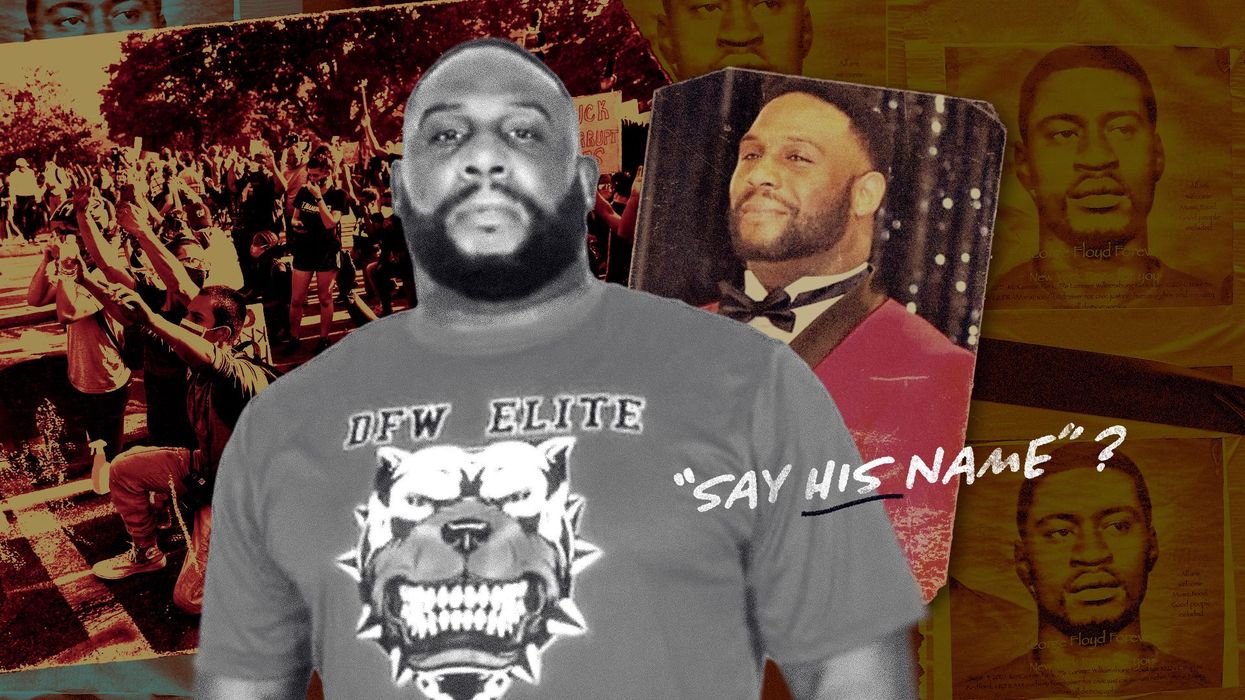

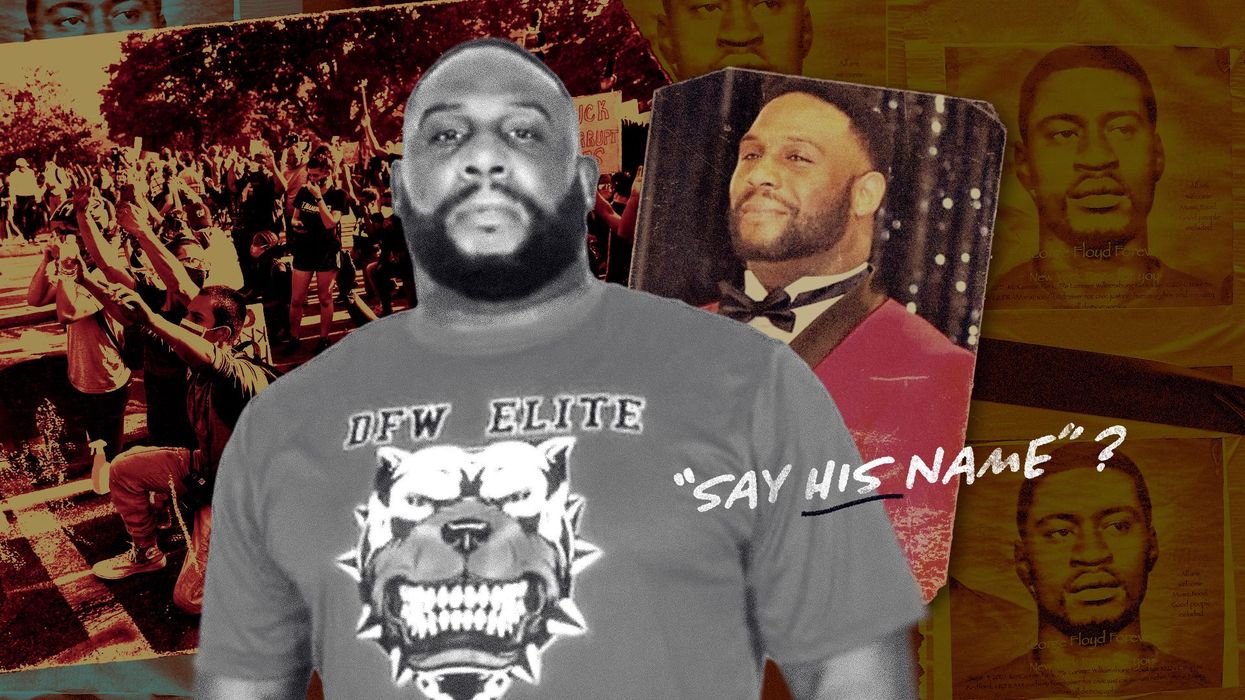

Corporate media has made it taboo to discuss the cultural rot at the root of black men randomly killing each other. So you’re unlikely to see a “say his name” campaign focused on Mike Hickmon.

Hickmon is unworthy of the kind of deification corporate and social media reserve for heroic black men harmed while resisting arrest. Hickmon is no George Floyd, Michael Brown, Daunte Wright, Rayshard Brooks, Jacob Blake, or Eric Garner.

Hickmon was a father, husband, active local church member, a former running back at the University of North Texas, and a little league football coach.

Saturday night in Lancaster, Texas, an opposing coach gunned down 43-year-old Mike Hickmon in front of 80 Pee Wee football players.

Following a scrimmage between players 9 years and under, the adult coaches engaged in an on-field brawl sparked when someone kicked the ball Hickmon attempted to pick up from the ground.

According to police, Yaqub Talib, the brother of a former NFL star, ended the melee, shooting Hickmon dead. Hickmon’s 9-year-old son was on the field at the time. So was Aqib Talib, the former five-time Pro Bowler, Super Bowl champion, NFL broadcaster, and brother of the alleged shooter.

The atrocity that befell Mike Hickmon illustrates a problem plaguing black neighborhoods that we’ve been groomed to ignore. It’s racist to discuss the self-hatred that provokes black men to cavalierly settle disagreements with gun violence.

According to approved media wisdom, the random, senseless murder of black men by other black men within black communities is a proximity crime that can only be solved by money, integration, and the passionate affection of white people.

Mike Hickmon would be alive today if white police officers properly loved black people.

So would Hickmon’s sister, Jennifer.

In July 2020, Jeffrey Alan Scott confessed to murdering Jennifer Hickmon, a 37-year-old middle-school teacher, volleyball coach, and mother of one daughter. Jennifer played basketball at Texas Southern University. She earned a master’s degree in education from Concordia University Texas.

In separate incidents, a brother and sister who used athletics to earn college degrees and dedicated themselves to helping young people were murdered by black men.

But we won’t shout their names. They’re victims of proximity homicides. Those murders don’t matter. There are no white people to directly blame.

Lancaster is a working-class suburb approximately 15 minutes south of the Oak Cliff, Dallas, area where Mike and Jennifer Hickmon grew up. Of Lancaster’s 41,000 residents, 65% are black and 23% Hispanic. The city has produced a handful of journeyman NFL players. Its most famous native is perhaps former Duke basketball player Thomas Hill, who was a shooting guard for the Blue Devils during the Christian Laettner-Grant Hill era.

Yaqub and Aqib Talib, raised by their single mother, grew up in Richardson, Texas, a northern suburb of Dallas. Twenty-five miles separate Richardson from Lancaster. Talib and Hickmon fit the corporate media’s proximity profile.

What’s the solution? Should black people distance themselves from each other?

Given that Aqib earned more than $70 million during his NFL career, it’s hard to blame poverty for Yaqub shooting Hickmon.

Maybe poverty and proximity don’t explain the astronomical murder rate impacting the life expectancy of black men. Maybe it’s a culture of self-hate and disrespect? Maybe the pursuit of white love doesn’t cure black self-hate? Maybe the matriarchal culture adopted by American black people foments emotional men with no impulse control?

It’s just a thought.

Popular culture has certainly normalized the denigration and destruction of black men. It’s so normalized that American media companies seem to prefer black broadcasters with “street” credibility.

At this time, we don’t know Aqib’s role in the Mike Hickmon tragedy. We know that Aqib was there. Based on Aqib’s history, it’s hard to imagine a fight breaking out and Aqib choosing to sit it out.

In 2008, he engaged in a brawl at the NFL rookie symposium. In 2009, he was arrested after an altercation with a taxi driver. In 2011, Aqib and his mother were suspected of firing a gun at his sister’s boyfriend. In 2017, Aqib and Raiders receiver Michael Crabtree had an ugly on-field skirmish. Aqib snatched a gold chain from Crabtree’s neck.

Shortly after Aqib's 2020 retirement, Fox Sports hired him to broadcast NFL games. Within the last few months, Amazon named him part of its team to broadcast Thursday Night Football.

Corporate media love black men with “street” credibility.

It’s all part of promoting a culture of violence and disrespect among black people who live in close proximity to each other. That’s why gangsta rappers such as Jay Z, Snoop Dogg, Ice Cube, Dr. Dre, and Ice T are presented as spokesmen for the black community and Ben Carson, Thomas Sowell, and Clarence Thomas are framed as sellouts.

You can discern the agenda of corporate and social media by the names black people are told to shout, the victims we’re told to idolize, and the men deemed worthy of an outpouring of emotion.

Mike Hickmon, a college graduate, a father, a husband, an active member of his church, a volunteer football coach, meets all the criteria to be regarded as a pillar of his community. But he’s no George Floyd.

That speaks to a deadly cultural rot.

Editor's note: This article has been corrected to note that Jennifer Hickmon was killed in 2020, not 2021.

Jason Whitlock

BlazeTV Host