(AP Photo/Olga Rodriguez)

The Washington Post recently published an article by reporter Jeff Guo entitled, “Why Black Workers Who Do Everything Right Still Get Left Behind.”

In Guo’s terminology, “black workers who do everything right” are those who get a college education, and “left behind” refers to an alleged 18 percent wage gap between college-educated black workers and white workers.

Guo’s explanation for this wage gap is “discrimination,” which suggests that employers are so racist that they will lose profits by paying white workers extra money to perform the same work that black workers will do for up to 18 percent less. Guo’s claim accords with the 2016 Democratic Party Platform, which declares that racial “disparities in wealth cannot be solved by the free market alone” but require the federal government to do more.

Guo bases his claim on a study from the Economic Policy Institute (EPI), but he flagrantly mispresents it. Moreover, the study itself is flawed, because it fails to account for important factors that relate to this wage gap. As detailed below, once these factors are taken into account, this allegation of discrimination falls apart.

In 1964, the U.S. enacted a major civil rights law that forbids racial discrimination in private-sector employment. Congress then expanded this law in 1972 to forbid discrimination in all government jobs.

For years since these laws passed, certain politicians, journalists, and activists have claimed that the job market is still biased against people of color. For a prime example, in 1999 Democratic Vice President Al Gore gave a speech before the NAACP in which he stated:

At a time when African-Americans earn just 62 cents on each dollar that white Americans earn, don’t you think it’s time for an equal day’s pay for an equal day’s work?

This “62 cents” statistic cited by Gore is extremely misleading, because it is merely a measure of median cash income per household (which in 1998 was $40,912 for white households and $25,351 for black households). The problem with Gore’s figure is that it fails to provide any information about “an equal day’s work,” as he said it does.

Easily-measured factors that affect work hours and productivity account for the vast bulk of this income gap. These factors include education, English fluency, and marriage, which propels men to significantly increase the number of hours that they work.

As in 1998, in 2014 the median cash income of black households was 62 percent of white households. However, the median cash earnings of married, U.S.-born black workers with bachelor’s degrees or higher was 89 percent of white workers with the same characteristics. In other words, these factors narrowed the income gap from 38 percent to 11 percent.

The remaining 11 percent gap may be caused by other factors that are harder to accurately measure in terms of their relationship to wages. Probable candidates for this are the career choices and practical skills of workers, which are dramatically different for college-educated whites and blacks.

A 2016 study by Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce found that black college students:

Another determinant of earnings is the practical skills of workers. In 2003, the American Institutes for Research assessed the literacy skills of a random sample of graduating college students. This study found that among graduating students at 4-year colleges:

Once practical skills and career choices are taken into account, it may be that college-educated black workers are paid more than white workers for an equal day’s work. As detailed in a 2004 paper in the Stanford Law Review:

Nearly all graduates of law school who want to practice law must take bar exams to begin their professional careers. These [academic achievement] uniformities make [racial] comparisons within the legal education system much easier.Blacks [who pass the bar exam] earn 6 percent to 9 percent more early in their careers than do whites seeking similar jobs with similar credentials, presumably because many employers (including government employers) pursue moderate racial preferences in hiring.

Like Gore’s statement, the EPI study is plagued by a failure to account for factors that impact wages. Although the study controlled for education and other variables like age, it did not account for English fluency, career choices, or practical skills. Thus, it was bound to produce pointless results, because it did not compare apples to apples.

To EPI’s credit, the study mentions more than 100 times that the wage gap it calculated is due to “unobservable” factors, which may include “discrimination,” worker “skills,” and other variables. However, worker skills are not “unobservable”—they were simply unobserved in this study.

This leads to another key point. The EPI study did not measure discrimination, despite the fact that it uses this word more than 100 times. Instead, the study’s authors employed a “frequently misused” statistical technique called a “regression” to calculate how much of the black/white wage gap was due to “observable” and “unobservable” factors. Then without evidence, they assumed that one of the “leading” unobservable factors must be discrimination.

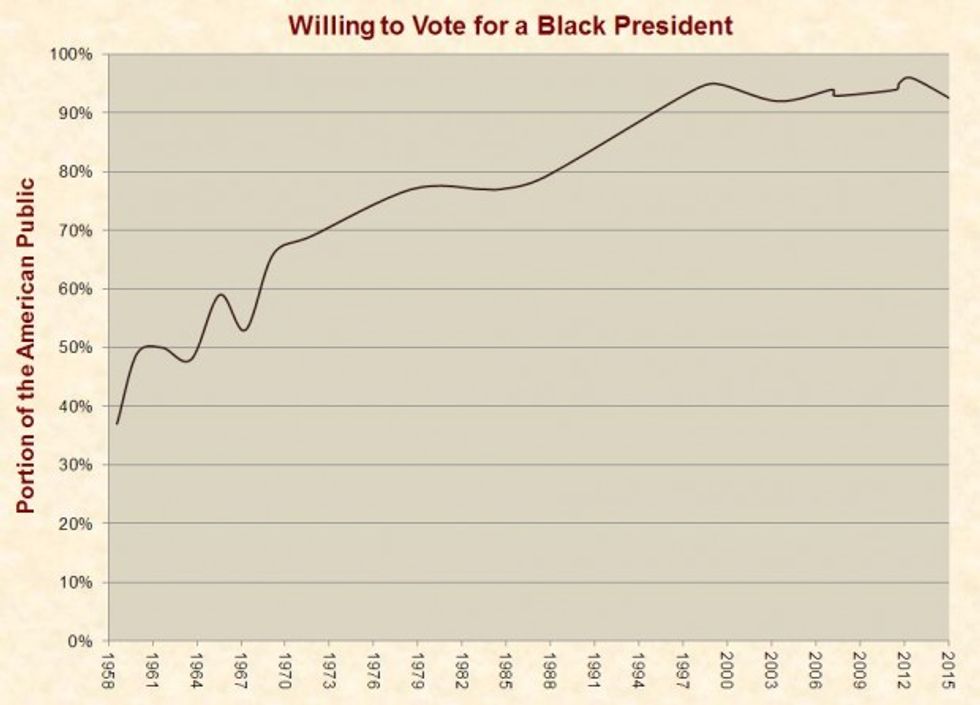

As a result of that assumption and the study’s finding that the black/white wage gap is higher now than it was in 1979, the authors concluded that racial discrimination is worse now than it was four decades ago. This claim is at odds with data showing that discrimination has declined over this period. Gallup polls show that the portion of Americans willing to vote for a black president rose from 77 percent in 1978 to 95 percent by 1999, and it has hovered around this level since then:

As explained by Gallup, 95 percent is “essentially universal willingness to state to an interviewer that the race of a candidate for president would make no difference.” In fact, the portion of non-white voters willing to vote for a black president is essentially the same—98 percent in 2012 and 93 percent in 2015. These figures are all within the polls’ margins of error.

In Guo’s Washington Post article, he uncritically parrots the EPI study and then worsens its flaws by burying its most crucial caveat. Despite EPI’s repeated statements that the wage gap calculated in its study is due to unobservable factors, Guo fails to directly state this. Instead, he waits until the 20th paragraph to slip in this craftily worded nod to reality:

The researchers blame this [wage gap] largely on rising discrimination, which they say may have resulted in part from the increasingly lax enforcement of anti-discrimination laws. That is one of the few explanations left after they controlled for a slew of other factors, including differences in education levels, local labor market conditions, industry structure, unionization rates and years of experience.

An honest article about this study would have stated that there are critical factors it did not account for—and it would have stated this early on. Instead, Guo front-loads his article with racially charged rhetoric like “the penalty for being educated-while-black was about 18 percent” in 2014. Such irresponsible journalism can produce disastrous outcomes, such as:

In sum, Guo’s “evidence” of job market discrimination is misleading, and his false accusation could worsen serious problems that are already harming many people.

James D. Agresti is the president of Just Facts, a nonprofit institute dedicated to researching and publishing verifiable facts about public policy.

–

TheBlaze contributor channel supports an open discourse on a range of views. The opinions expressed in this channel are solely those of each individual author.