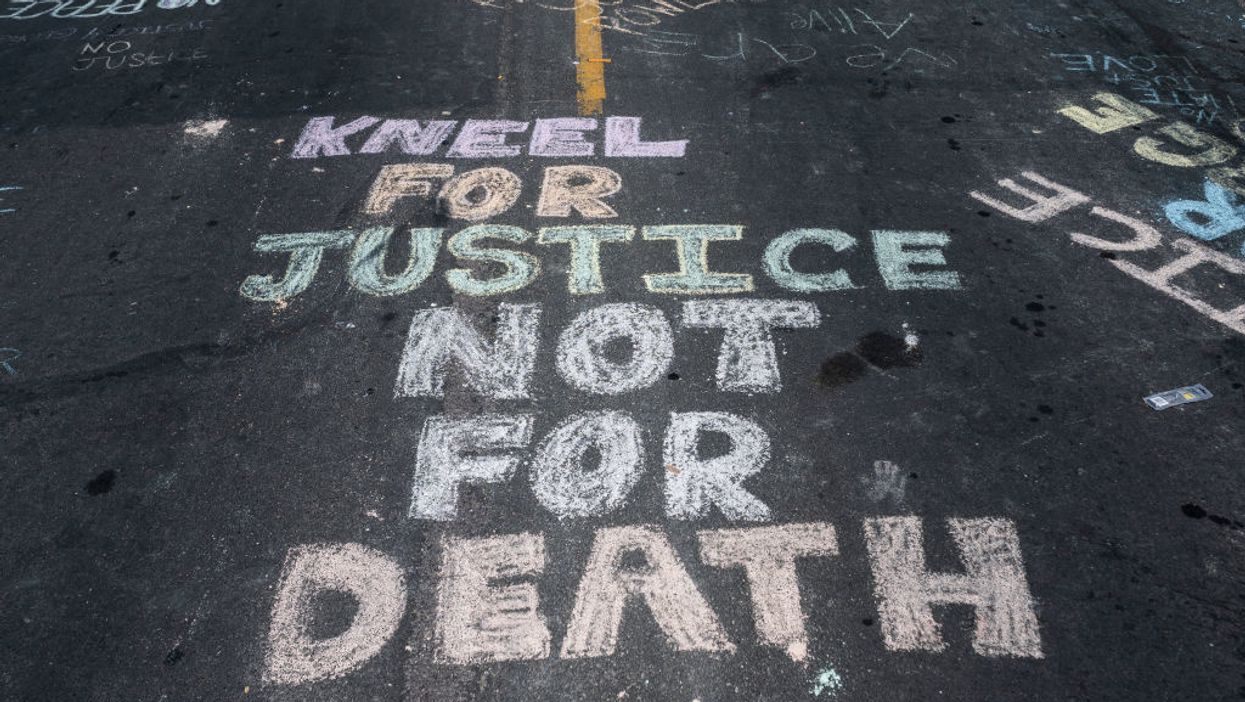

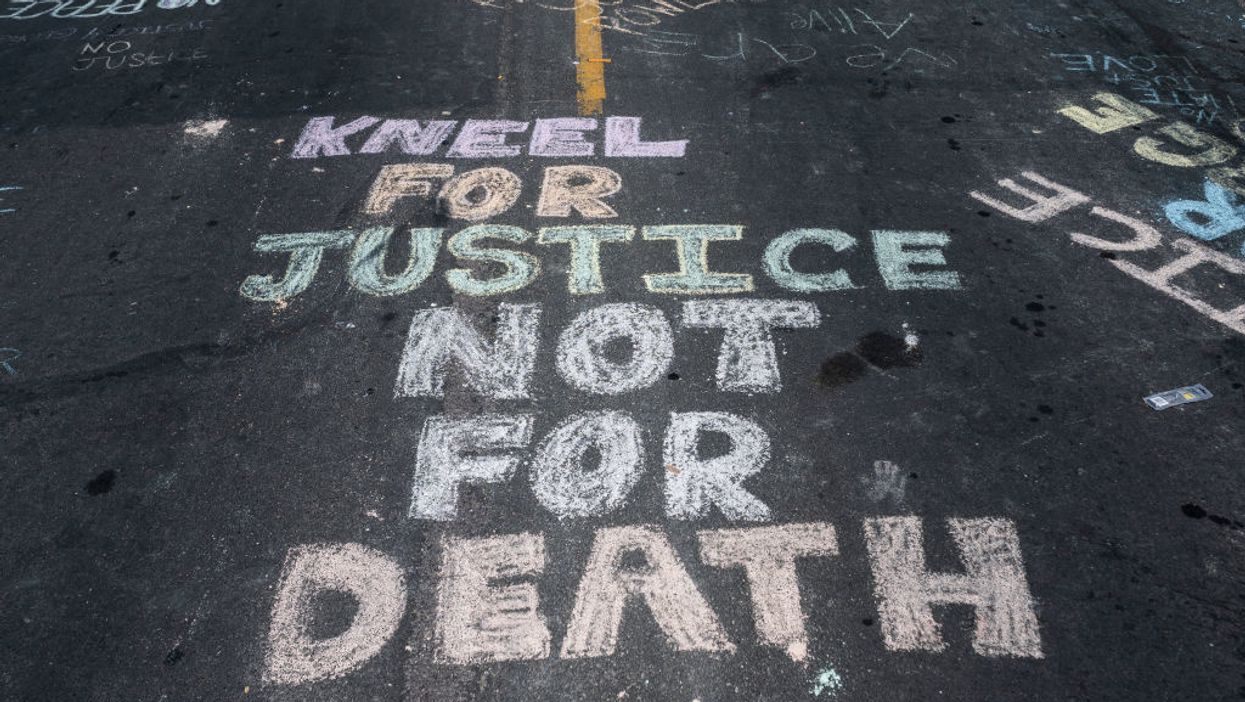

Photo by Stephen Maturen/Getty Images

We must demand better

On March 13, armed men that he did not know forced themselves into the apartment of Kenneth Walker's girlfriend Breonna Taylor, allegedly without announcing that they were police. Because, as we now know, Taylor was not a drug dealer or otherwise actively involved in crime of any sort, Walker had no reason to believe the men were anything other than home intruders, so he shot one of them, who tragically turned out to be a police officer.

Walker was promptly arrested and charged with attempted murder of a police officer. He was held incarceration for weeks until he was released to home arrest due to coronavirus concerns. When he was released to home arrest, the Louisville, Kentucky, police chief publicly condemned the decision, saying, "It's hard for me to see how a man accused of shooting a police officer falls into that low-risk category and I am very frustrated by Mr. Walker's release to home incarceration." No mention was made of the fact that the police in question had shot his girlfriend — who was, as far as we know, not guilty of any crime — 8 times, killing her.

Ultimately, of course, the charges against Walker were dropped, but only after he spent two months in various forms of incarceration.

Meanwhile, in Minneapolis, officers who knelt on the prone body and neck of George Floyd for several minutes after he was subdued, drawing widespread condemnation even from other police departments, walk free. The county attorney took to his podium Thursday and lectured the public about rushing to judgment, and the need for a slow and thorough examination of the evidence before considering criminal charges of any kind against the police officers involved.

I submit that this is completely backward, and is symptomatic of a mistake that we as a society cannot continue to make, if we value our freedom.

I am well aware that police have a difficult job. I am also well aware that most of them do it professionally and competently, and are deserving of our thanks and respect. I think in general, our society should continue to respect police and perhaps could respect police a little more than they currently do.

However, I think there should be a permanent realignment of how we should view the situation when someone who is either confronted by police or in the custody of police dies.

Yes, police officers are given a difficult job, and are often sent into difficult and dangerous situations, and for that they deserve our thanks.

There is another side of that coin, however. They are also given guns, and tasers, and batons, and empowered with the right to take away our freedom and our lives. The price of remaining free when people walk among us with such power is eternal vigilance and oversight about how that power is used.

That applies with special force when a person is killed. As a society, most states have retained the death penalty, but it is reserved for the very worst of criminals who have been properly tried, convicted, and had all their appeals exhausted. It is not a penalty for police to mete out on a whim.

When a person dies at the hands of police, the presumption should be that something has gone horribly wrong, and just like with any other person — or perhaps even more so than any other person — the onus should be placed on the officer to prove that the use of lethal force was absolutely necessary to protect either the officer or another innocent person from death or serious bodily injury. That presumption must exist if we do not want a society where police go around shooting people on the spot, or being reckless with the use of lethal force.

Here is a principle that was well understood by the Founding Fathers of this country, as well as by anyone who values their own freedom: People will use whatever power you give them, and then they'll seek to take a little more. It is the reason why our Constitution was written with the obvious primary aim of fencing in the authority of people to whom the power of life and death is given (our government), including the police.

A society that loses the ability or the will to aggressively question their government when their government attempts to constrain their freedom or their lives will not remain free for long.

We, as a society, went too far in forgetting that lesson, and we are seeing the consequences of that now.

Consider, if you will, the aftermath of the Eric Garner case in 2014. Let's set aside for a second the complicated racial issues involved in that case, and even set aside for just a moment whether the force New York City Police Officer Daniel Pantaleo used to bring Garner to the ground was necessary or appropriate. After Garner was subdued and repeatedly told officers he could not breathe, they rolled him onto his side and then, rather than giving or even attempting medical attention to a person in their care, stood around talking while Garner literally died at their feet waiting for an ambulance to arrive.

Yet in spite of the fact that the entire interaction was caught on video, and despite the fact that the carotid bar used by Pantaleo had been banned by the police department, and in spite of the obvious callous disregard shown for Garner's life after he was subdued, a grand jury refused to indict Pantaleo in spite of massive public outrage. This happened for one simple reason: At least four people on that grand jury were willing to extend Pantaleo literally any benefit of the doubt he asked for.

And what, do you think, was the message that was sent to police officers across the country by that decision? Do you think it perhaps had some effect on the officers who knelt on George Floyd, in terms of whether they felt like they wouldn't be held to account criminally if Floyd died while in their care?

More importantly, what message do you think it sent to communities who have long felt (rightly or wrongly) unfairly targeted by the police? Do you think perhaps that people who are currently enraged are enraged more by the fact that police officers are so seldom held to account for bad behavior than they are by the bad behavior itself?

The problem is not anecdotal. In the wake of Garner's death, an analysis was conducted of officer-involved shootings in New York City. That analysis found that in the last decade, there had been 180 people shot and killed by New York City police officers. The officer involved was indicted in only three of those cases, and in only one single case was the officer convicted of any crime — and that for a non-jail-time offense.

I submit that these numbers are nearly irrefutable evidence that people — from district attorneys to grand juries on down — are giving entirely too much benefit of doubt to police. It ought to strain the credulity of the most proud displayer of the thin blue line flag that 179 out of 180 officer-involved shootings in the same department were totally justified, nothing-to-see-here cases.

We would not expect an error rate so low in any other human endeavor, but when it comes to cops and people dying, too many people don't even blink at extending that benefit of the doubt, never thinking about what it might mean for them if they find themselves in such an unfortunate encounter with someone who has a badge and a gun. We know, instinctively, that there are bad, dishonest people in the world who are petty tyrants with every bit of authority that is granted to them, but we somehow seem to believe that none of those people become cops.

And when it occurs that police kill people, and time after time after time after time are not held to account, how effective is the message to those who are aggrieved that they should protest peacefully and trust that the system will work?

I believe two different things at the same time: 1. That police generally do a good job and deserve to be respected; and 2. The system is abjectly broken when it comes to holding bad police officers to account.

I also believe that item No. 2 makes the job of the good police officers more difficult. Because when people believe that bad police officers will not be held to account when they literally kill people, they tend for some bizarre reason to get upset. After years and years of seeing it, they tend to not have faith in peaceful protests and letting the system work. They tend, in other words, to force good cops to clean up the messes left behind by the bad ones.

And I also believe that item No. 2 is mostly our fault. You and me, and all the other ordinary citizens. People who have sat on juries and grand juries and looked for literally any excuse to not convict or charge police officers when people die. We are the ones who have caused district attorneys to be extraordinarily hesitant about charging cops, correctly believing it to likely be a waste of time.

To be sure, the district attorneys themselves bear some blame for lack of courage, as do some of the "good" cops who would never use excessive force themselves but would also never testify against their fellow cops who do. Remember, after all, the galling spectacle of the head of the NYPD union blasting New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio for firing Pantaleo, after most of the rest of the country thought he should be in jail. The entire criminal justice system could stand a look inward and a healthy self-examination about this problem. But fixing the problem starts with us.

I believe that the default assumption should be that when a person shoots someone who is entering their home in the dead of night, they are justified in doing so. I believe that the default assumption should be that when a police officer shoots a private citizen, something has gone wrong and the onus should be on the officer to justify his actions. Obviously, in the majority of situations, the officer will be able to produce evidence to justify what happened. I do not believe that the majority of officer-involved-shootings are anything other than justified. But we need to see and demand proof, especially in the era of widely available and cheap body cameras.

And when a situation unfolds like the fiasco in Louisville, where officers were suspiciously not wearing body cameras in spite of the fact that they are widely worn and available by the Louisville PD, the default assumption should have been that the officers involved should have gone to jail and Kenneth Walker should have walked free, until compelling evidence emerged to the contrary.

And in Minnesota, it might emerge that there is evidence to prove that the force used to subdue George Floyd was reasonable and necessary, although I can't imagine what that might possibly be. But neither the district attorney nor us as the public should be extending the benefit of the doubt.

This does not mean that I am calling for an end to due process for police officers. Far from it. I am calling for the same due process that is given to everyone else. If you are caught having killed someone, and your claim is that it was justified due to self-defense or defense of others, then the burden is on you to prove that as an affirmative defense to the charge of murder. That affirmative defense, and the evidence you offer, will be thoroughly scrutinized and tested by law enforcement and the district attorney, and eventually potentially by a jury. If someone dies because of your actions as a private citizen, you are going to face some pointed questions from some skeptical people, even if you were totally justified. Thus it should be with the police.

Eternal vigilance is the price of our freedom, and our lives. It's time we started paying it.