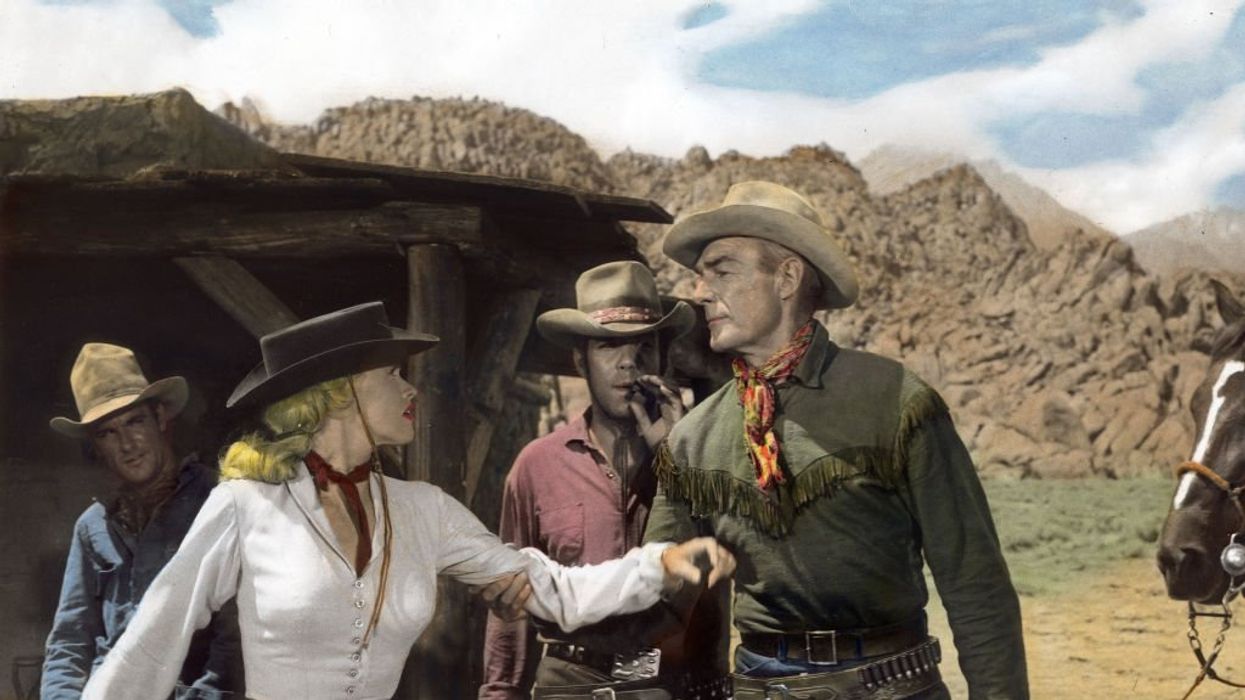

United Archives/Getty Images

The bleakest, darkest movie of the Ranown Cycle reveals the alienation at the heart of the Western hero.

"Ride Lonesome" is part of Budd Boetticher’s six-movie Ranown Cycle. I covered much of this in the Wednesday Western article about "The Tall T," so I’ll keep this simple. “Ranown” is a portmanteau of Randolph and Brown, as in Randolph Scott, the leading man who was 61 years old at the time, and Harry Joe Brown, the executive producer.

Besides "Decision at Sundown" and "Buchanan Rides Alone," the Ranown films also share a location: Lone Pine, California, all dust and sky. It’s the perfect backdrop for these moody, violent films, God’s Earth in widescreen and CinemaScope.

Imagine if Boetticher had had 'Gone with the Wind'-level financial clout. With such a formidably talented roster, the Ranown Cycle films could very likely have launched Boetticher into John Ford territory, fundamentally reshaping the future of film.

"Ride Lonesome" evinces the bareness and minimalism that make the Ranown Cycle so desolate, only better, deeper, darker.

The imagery veers into an existential terrain that, in my opinion, is bleaker than the others. It’s a film pocked with anxiety and broken shelter, a bare life.

Bounty hunter Ben Brigade (Randolph Scott) unites with a murderer Billy John (James Best), and they begin their journey into a desert crawling with menacing outlaws and Mescalero Apaches.

Scott is soft-voiced but firm and assertive. Doesn’t talk much, but he’s exceedingly aware of his surroundings.

Even the houses are broken and minimal, whatever could be cobbled together in a land of scarcity. Nothing feels safe. The music whimpers like it knows something.

The characters are repeatedly confronted by the hanging tree, a symbol the camera returns to again and again. The ghoulish tree might even be the central figure of the entire story.

Meanwhile, the costumes and set design are colorful, stylish, bright. This dichotomy of light and dark is classic Boetticher.

And how about that closing scene? I would place it high on the list of perfect endings.

Boetticher’s Ranown Cycle lasted a mere four years, between 1956 and 1960. Other classics released in 1959 include "Ben Hur," "Anatomy of a Murder," "North by Northwest," "Some Like It Hot," and "Black Orpheus." Disney’s "Sleeping Beauty" also came out that year. "Ben Hur" dominated the 1960 Academy Awards, with 11 Oscars. Boetticher, meanwhile, only ever got one nomination, for his first movie, about the bullfighter.

There weren’t many other Westerns released in 1959 — "Warlock," "Westbound," "No Name on the Bullet," and "The Hanging Tree." "Ride Lonesome" and "Rio Bravo" are probably the two most important.

"Ride Lonesome" mostly transcends its time, although the trumpet-driven soundtrack is characteristic of the era, as is Karen Steele’s cone-shaped bra.

"Ride Lonesome" is as lean and tidy as most of Boetticher’s work, clocking in at 73 minutes.

All of the Ranown Cycle movies are short because Boetticher was cursed to the B-film circuit after John Wayne and John Ford clipped his first film, "Bullfighter and the Lady," so heavily that it finishes in under 90 minutes, relegating it to the lesser slot of the double feature.

These low-budget endeavors ("Ride Lonesome" was filmed in 17 days) serve as a connective style between the valiant Westerns of the early days and everything that followed.

Criterion Collection takes this idea further than it should go, in my opinion, claiming that the Ranown Cycle provides “a crucial link between the classicism of John Ford and the postmodern revisionism of Sam Peckinpah.”

I mean, they’re right — the Ranown Cycle is (mostly) a masterpiece, a feat of creative minimalism that departs from the so-called typical Westerns of the 1930s–1950s. But they’re also wrong, an accusation I don’t make lightly, against an iconic brand that, for a couple decades, has connected me to cinematic masterpieces.

I guess I just don’t like the “link” metaphor. It also feels like posthumous acclaim. Boetticher was blessed with Hollywood connections, earning admiration from lots of higher-ups and legends. Sergio Leone loved Boetticher’s Westerns. Lots of visionaries did and do.

But he still spent four decades in the shadows of B-movie status, locked into a scarcity mindset, with limitations on cast size and production and even storylines, which forced Boetticher and the gifted cinematic craftsmen at his side to strip every element to its essence.

The Ranown films were each made for less than $500k, and they didn’t exactly shovel in the money at the box office. They became popular in Europe, like many of the low-budget renegade Westerns from that era — Jean-Luc Godard once said of Nicholas Ray’s "Johnny Guitar" that “there is cinema. And the director is Nicholas Ray."

In hindsight, thank God for these restrictions and the inventiveness they inspired.

But what if the budget had been much larger? Imagine if Boetticher had had "Gone with the Wind"-level financial clout. With such a formidably talented roster, the Ranown Cycle films could very likely have launched Boetticher into John Ford territory, fundamentally reshaping the future of film.

It is shocking that budgetary hindrances didn’t ruin the artistic uniqueness and bravado that still explodes from the screen.

There’s also the issue of the Ranown Cycle’s place on the team bench. High-brow cultural elites love to dig up obscure remnants of culture and history, only to proclaim that all the rest of us don’t realize that we had been using a masterpiece as a footstool.

Boetticher was known for his ability to scoop up gifted actors before they got famous.

The natural-born villain Lee Van Cleef had nearly perfected the viciousness and scowl that would help deepen in the grit of Sergio Leone’s Dollars Trilogy, after appearing in "How the West Was Won" and "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance," where his sneer made up for his lack of lines. The late 1950s marked an exciting period for Van Cleef. In the years leading up to "Ride Lonesome," he had worked with some of the most important directors of the genre — Samuel Fuller, John Sturges, Anthony Mann.

"Ride Lonesome" also marks James Coburn’s acting debut.

In the Wednesday Western article about "The Tall T," I only told the middle third of Budd Boetticher’s wild life. Let's rewind a bit.

He was born in Chicago, Boetticher’s mother died giving birth to him, and his father died shortly after when he was hit by a trolley car.

A wealthy family in Indiana adopted the infant orphan and named him Oscar Boetticher Jr. His adoptive father, Oscar Boetticher Sr., owned a profitable hardware company, Boetticher and Kellogg, and spoiled his kids.

Oscar Sr. was 50 when Budd was born, a disparity that grew as Budd got older. Their only shared interest was horses. So, young Budd ramped up his love for them.

His mother was 34 years younger than his father. Boetticher would joke that his father had bought the most beautiful woman in all of Ohio and Indiana.

His parents didn’t like each other much.

When he found out he was adopted, he was actually delighted.

He had always been bullied. So, he resolved to bulk up and fight back. Before long, he was a celebrated athlete in track and football.

Sports became his obsession. He went to a prep school so that he could tack on mass, gaining 20 pounds of muscle. He was football captain and track captain.

He earned a position on the Ohio State football team. Just as he was making a name for himself, a knee injury sent him to the bench. Boetticher recovered for the rest of the year, then a second injury blew out his knee. The doctors warned that if he continued to play and hit his knee again, he’d have a stiff leg for the rest of his life.

Boetticher’s doctor urged him to go on a trip in order to process the injury. So, he went to Mexico City, where he encountered bullfighting for the first time.

There aren’t many characters in "Ride Lonesome."

Men and women belonged to a different society than they do today, in the historic West as well as the Hollywood sets made as their imitation.

Plenty has been said about the superlatively masculine Western man. The women of Westerns don’t get enough admiration. In particular, their portrayal of women whose fullness reaches all the way back to Eve but not as far back as Adam’s rib.

In Westerns, the cruelty of a woman’s life back then takes on a new form. Redemption. Times have changed. Times are continuously changing. So, in these movies, portrayals of women, especially in motherly hardship, serve as testimony of survival. True grit.

Other times, the female characters reveal an empowerment that has long been ransacked by feminism. The sweep to occupy womanhood has led to the eviction of some of women’s most lovely and charitable strengths.

Masculinity is a primary theme within the Western. "Ride Lonesome" is no exception. Well, not exactly. These frontier men are as stoic as expected. But as the title reveals, "Ride Lonesome" contains a pervasive alienation at odds with the image of the Western man as an agent of freedom beholden to nobody.