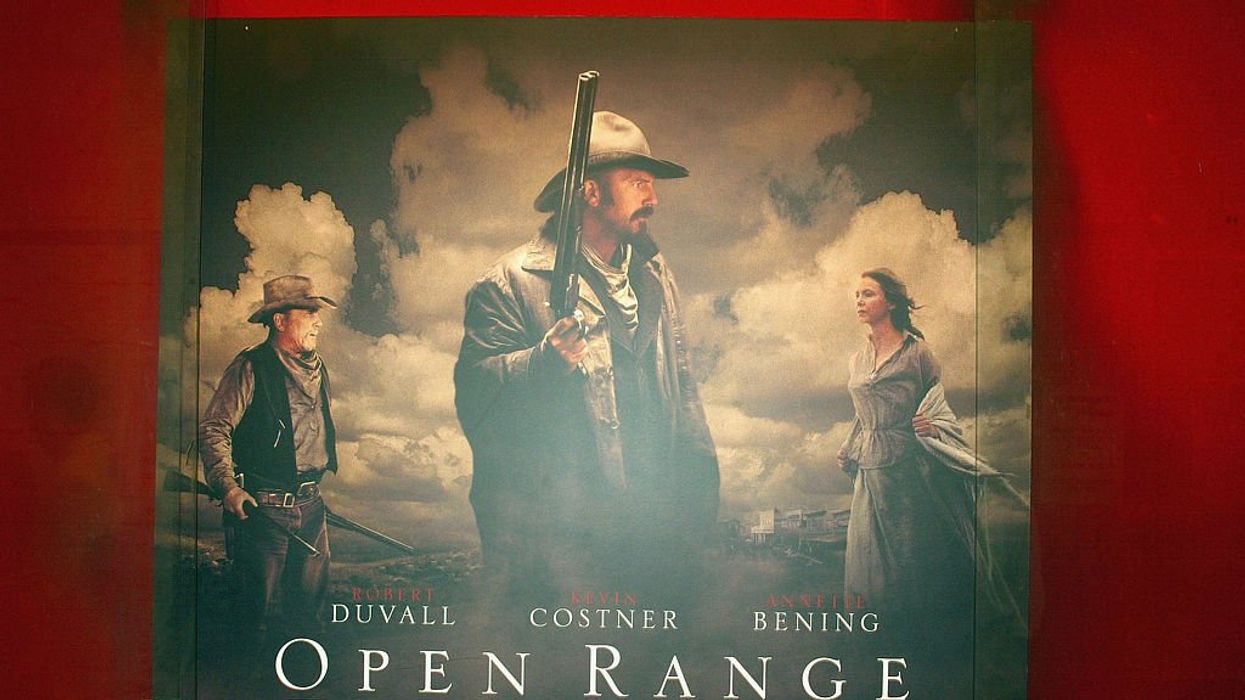

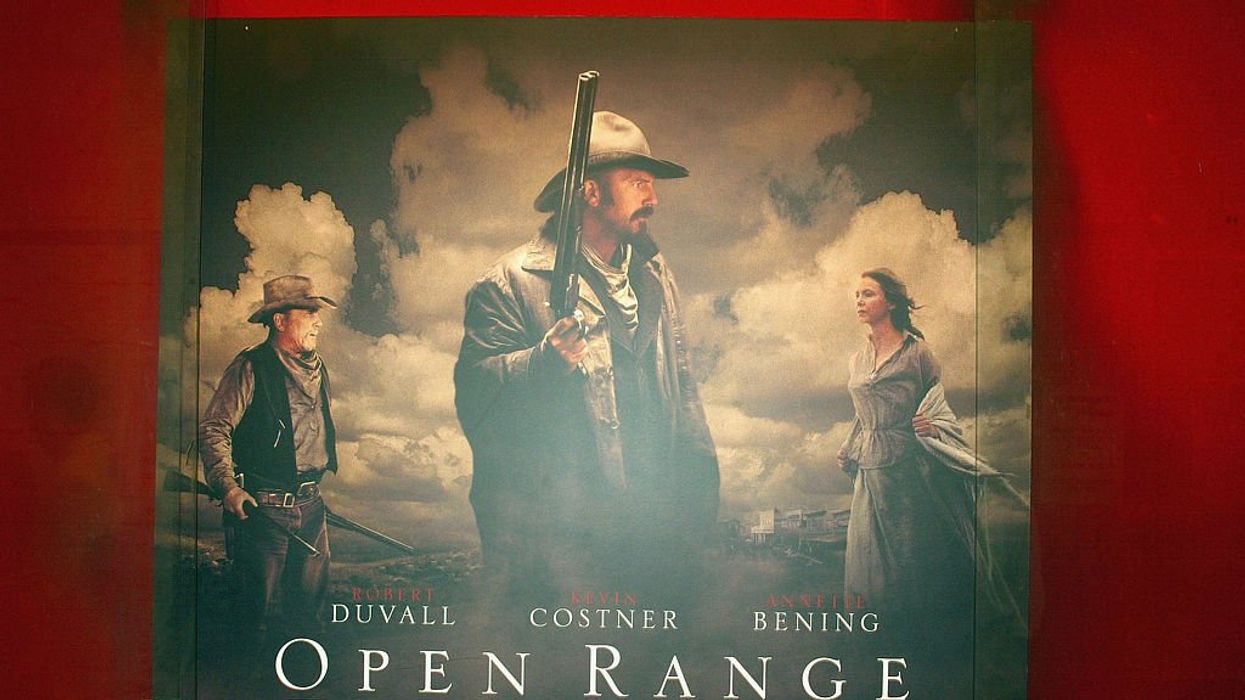

Pascal Le Segretain/Getty Images

Kevin Costner spared no expense to get the details of his return to the genre right — and it shows.

Law is imposed and upheld by force. When formalized, it is then used to dominate anyone who challenges its legal and political origins.

During the 19th century, this lawmaking process occurred throughout the American West — especially with the charting of its geography.

Costner provides one of the great gunfight scenes in the history of the Western: loud, sloppy, feverish, brutal, vicious — a shoot-out so good that an otherwise PG movie earned an R rating.

Unclaimed territory presented a unique opportunity, where anyone crafty enough — regardless of their social status — could assert themselves as new American gentry. All they had to do was conquer a wilderness full of hostiles of every type and species.

This journey across virgin terrain signified both total freedom and total potential for power. The open range was a world without boundaries, only endless hills and verdant pastures. But slowly, these wildlands accommodated wanderers, then settlements, then towns. Just as borders follow war, the regulation of the open range arrived in the form of barbed wire.

"Open Range" screenwriter Craig Storper has said he aimed to craft a movie about "the evolution of violence in the West."

Our two heroes — cattleman Boss Spearman (Robert Duvall) and his second in command, Charley Waite — occupy a pivotal time in that evolution, the moment when a few men channeled violence to assert their claim to vast amounts of land.

"These characters don't seek violence,” Storper says, but it turns out the be the only path to resolution.

“Open Range” begins with Spearman and Waite wandering a heavenly frontier.

They have spent the past decade guiding free-range cattle through the West. Now their endless meadow is being domesticated. The open range has been crowned with coils of razor fence.

They may be roughnecks, but they take their hierarchy seriously, especially in view of the subordinate cattle hands, Button and Mose, who both have a childlike glow, a playfulness.

By the time the credits finish, the Eden-like day collapses into dark as the four cowpokes find themselves trapped in the plains by a torrential downpour. The storm forces them to wait out the rain with card games and banter as they squander their supplies.

Mose treks to the nearby town of Harmonville to replenish their stores. Mose is played by “ER” mainstay Abraham Benrubi, who, at 6’7” and 300 pounds, typifies honest strength, a sort of Andre the Giant figure too imposing for most hoodlums to bother.

When Mose doesn’t return, Spearman and Waite ride into the town. Nastiness and corruption await them. They learn that Mose was ambushed, beaten to the point of broken ribs, and tossed into a jail cell.

Our two open-range heroes are then rebuffed by Irish-born rancher Denton Baxter (Michael Gambon), who tells them: “Folks in Fort Harmon country don’t take to free-grazers, or free grazing. They hate them — more than they used to hate the Indians.”

(Note that there are no Indians in the movie, a deliberate choice by Costner to highlight the hostility of the town’s gatekeepers.)

At the time, 1882, free grazing was still legal. But the gatekeepers of Harmonville are ready to put an end to the practice by any means necessary, legal or not.

On one side of this crisis, there is total openness, the libertarian drive to be left alone. On the other, total confinement and demarcation, authoritarian in nature.

Baxter serves the devil well, a pitiless, blood-starved maniac with a passion for Machiavellian schemes.

This of course leads to a rivalry between the mysterious lawful outsiders and the criminal dignitaries in charge of local justice. The politics of the dynamic immediately start to boil. Good-bad versus bad-good, like an army surrounding a pocket of accidental rebels.

It’s the exact sort of situation known to shake a gunslinger right back into action. And in the heat of this battle, the dormant heroes will rise, overcoming past failures and past shame. But first they have to prepare for total violence.

What started as a desire to be left alone has now become an altogether more direct mission: to eradicate Denton Baxter and his horde of unkempt goons.

“Open Range” captures this scramble with the pause and dignity of a genuine openness, every confrontation miniaturized by the landscape.

As tensions escalate, Baxter’s thugs leer down at the cattlemen's camp in bloodied masks.

In the middle of prairie green, facing death shoulder to shoulder with Spearman, Waite asks, “You reckon them cows are worth getting killed over?”

“Cows is one thing,” Spearman replies, “but one man tellin’ another man where he can go in this country's somethin' else.”

The audacity of the villains sticks in Spearman’s craw. And now there’s no doubt that peace will first require warfare. It’s a sparse and jarring realization, as Michael Kamen's orchestral score tiptoes along. (Kamen also composed the soundtracks for “Die Hard,” "Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves," and “Lethal Weapon.")

Amid it all, there’s the local physician's assistant, Sue Barlow (Annette Bening), who has beautiful eyelashes and the courage to stand up for what's right. Like her fellow townspeople, she roots for outsiders to upend the community's corrupt ruling class.

It's obvious that Costner loved making “Open Range,” describing it as "a privilege and a thrill." He said, "I think if I never made another movie, I'd always be happy this was my last one."

He began his directing career with twelve Oscar nominations and seven wins for “Dances with Wolves” (1990), a film that ushered in a new era for the Western. “Open Range” marked Costner’s third directorial performance, following 1997’s “The Postman,” a strange post-apocalyptic drama. It was also a return home. Costner is at his best in the realm of the Western, which he describes as our "oldest genre.”

All the better if it sells tickets. “Open Range” justified its $22 million budget by grossing $68 million at the box office. And while it didn’t stir the Motion Picture Association, it earned a Bronze Wrangler at the 2004 Western Heritage Awards.

“Open Range” takes a literary approach to the screen that we return to throughout the Wednesday Western series. It's based on the novel “The Open Range Men” (1990) by Lauran Paine, whose 900 books include Westerns that Costner fell in love with, shaping his bare approach to storytelling.

Robert Duvall, appearing in his first Western role since “Lonesome Dove” nearly a decade and a half earlier, affirmed this sentiment: "The English have Dickens, the Russians have Tolstoy, we have Westerns."

The word “authenticity” recurs in analyses of “Open Range.” Partly, this refers to Costner’s devotion to accuracy, from the atomic level to the wide screen.

Costner’s process made every part of the film deeply personal and studious, even fine-tuning the knob-tweaking on lighting and sound. He extended this highly choreographed approach to the entire movie. He demanded from the start that nothing, no matter how small or plain, be superficial.

Even the most unnoticed props — utensils, tools, candy — were custom-made in order to be historically accurate. Particular attention went to the quality of the saddles and even more for weaponry. The guns had to look, sound, feel, and even smell like the firearms of the 1880s. Costner kept all his revolvers after the film.

Next, the authenticity of apparel. He was pleased with the plainness and accuracy of the costumes. The crew took pains to ensure that actors’ outfits were sullied and rumpled.

To match these optics, Costner enrolled the cast in an immersive cowboy boot camp. Costner and Duvall spent additional time with hardened sherpas of the forgotten West.

Beyond his decades in Hollywood, Robert Duvall has ranching experience. In his Texas-crafted leather boots, he brought Boss Spearman to life.

Likewise, Bening spent the nearly two-month filming roped into a corset. You’d almost forget that the “American Beauty” actress is married to Warren Beatty in the way she dignified the role of Sue, whom Bening described as "a woman of real substance and simplicity."

Costner chose Bening specifically for the role, giving her carte blanche in developing the character. He’s called her performance "timeless," adding, “This is how I'll always see her."

Then there’s the authenticity of the bond between Spearman, who pines for his days as a family man, and Waite, whom Costner described as "a good man who thinks he's bad.”

To cement this dynamic, Costner gave top billing to Duvall, whose casting was a prerequisite for the movie to be made. Throughout “Open Range,” the two actors improvise lines with the mastery of Western legends. In these moments, you can see the influence of Gary Cooper on Kevin Costner’s acting.

Over the course of long takes, Costner offers drama that unfolds organically. But the scenes had to be perfect. And they often were. Most were choreographed so well that many of them were shot in one take.

To build the setting around our heroes, Costner conscripted 225 head of cattle. Many others were digitized or mechanical in order to pepper the landscape with animals.

Then, zooming out wider still, Costner’s vision of the entire world they inhabit: “Open Range” is designed to feel wide open, engulfing the viewer.

Costner scouted the sweeping landscape of that first scene by helicopter. From that first glimpse, “Open Range” is a classy, gorgeous, cinematic whirlwind. The visual power of its imagery transports you to this bygone paradise, captured by the cinematography of James Muro, who also worked with Costner on “Dances with Wolves."

As for the town of Harmonville and the surrounding area, Costner would only settle for a completely isolated location. He rejected several full-scale iterations of the town.

Then, one day while riding his horse Cisco through the quiet nowhere of the Calgary hills, he found his hunk of marble, gently haloed by the Rocky Mountains.

The construction of Harmonville cost the studio over $1 million, including a $40,000 project to build a road to the build site.

Then, when Costner had sculpted his perfect world, the laws of nature played their part. Much of the film’s authenticity was a result of weather hardships that Costner and the crew endured.

Repeatedly, the set was berated by torrential rain. But these disruptions thickened the skin of the film, deepened its unpredictability. It’s hard to tell which scenes were real and which were fabricated — the flood down Main Street, crafted by technical crew, cost the studio $300,000.

Zoom out farther. Costner’s vision expands even broader than this, with thematic and historic intricacy beneath the flow of the action and dialogue. What does it all mean, in the commotion of existence? What does it reveal or liberate?

Then there’s the drift of the film, its tenor and pace. In the editing room, Costner reintroduced scenes he had intended to cut, resulting in the nearly 2.5 hour run time.

He said later that he deliberated a sense of lingering and slowness: “I really wanted people to settle down with this movie, with this place, and let them absorb our rhythms, the rhythms of the time.”

In the audio commentary for the movie, as our heroes prepare for battle, Costner says, “We're headed now where all Westerns need to go: the shoot-out. It would be a mistake not to end a Western with a gunfight. It's the tradition.”

He in turn provides one of the great gunfight scenes in the history of the Western: loud, sloppy, feverish, brutal, vicious — a shoot-out so good that an otherwise PG movie earned an R rating.

Painstakingly choreographed, including several digital renderings, the scene lacks all the usual superhero grace and smoothness of a set piece shoot-out. Costner (mostly) avoided the use of slow motion, so that the slowness feels natural and the haste perfectly dangerous and realistic. Pleased, he later referred to the scene as "a ballet."

The aftermath of the killings brings division among our heroes. With bodies layered into the mud, Waite reloads, so that he can execute one of Baxter’s thugs. The man is badly injured and defenseless. Spearman stands between Waite and the man.

“We come for justice, not vengeance. Now them is two different things,” says Spearman.

Without pause: “Not today they ain’t.”

"Open Range" is available on the usual streaming sites, including Tubi, where you can watch it for free.