Getty Images/DEA/C. SAPPA

I am an inveterate wanderer of library stacks. I could not count the hours whiled away strolling between bookshelves eyeing spines, reciting titles to myself, sometimes plucking a volume from its place to examine a cover. Once in a while, I open one at random to dip into the ceaseless ocean of words hoping to scoop up some unimaged serendipity.

You might call it a waste of time, but it is one from which I shall not repent. Those times in the stacks have produced innumerable treasures. Half my education I attained in this peripatetic fashion. You can call it a waste of time, but I will call it wisdom.

I was doing this very thing recently when I happened upon “The Oxford Book of English Verse” edited by Christopher Ricks. It was one of those fortunate surprises that brings new bits of knowledge to those who encounter it.

What do you know, for example, about Thomas Gray and his beloved poem "Ode on the Death of a Favourite Cat Drowned in a Tub of Goldfishes"?

I knew about this poet and his work just the same as you, which I will venture to guess is nothing, until very recently. I would have stayed in my ignorant state, too, had it not been for the good works of Mr. Ricks (of whom I also know nothing, but I have a pretty good inkling he knows his stuff when it comes to English verse) and the unknown but broad-minded librarian who had the good sense to invest in a copy of his tome.

Even more notable than my discovery was the context in which I made it. I discovered this book while meandering between the stacks of a little library here in an Ohio village. The whole place has an estimated population of under 1,600.

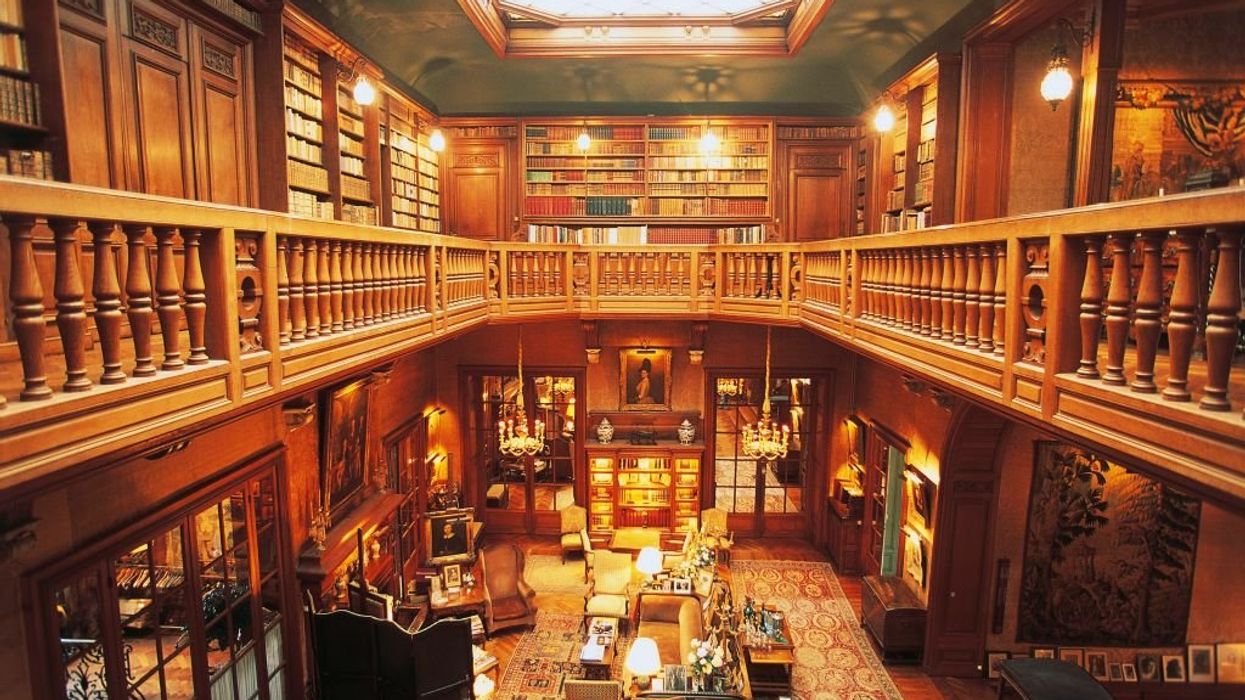

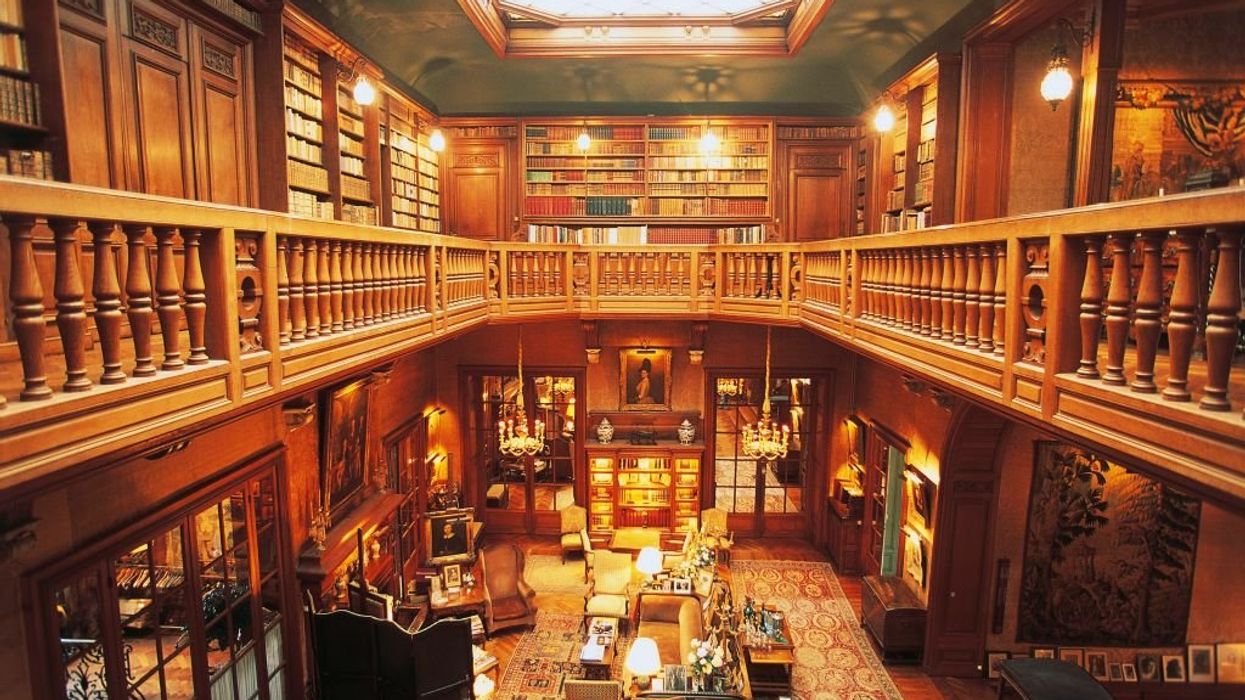

And yet, in its center lies this beautiful building housing so many volumes critical to the tradition of the West and the soul-shaping forces it exerts. Hiding here in Nowheresville, Ohio, are Dante, Tennyson, Wilde, Dickens, Twain, Melville, Fitzgerald, and so many others who made the world we once inhabited. Here, even here, in a place as culturally remote and irrelevant as possible, these treasures reside, ready to elevate anyone willing to pick them up.

Virtually no one does. The library’s copy of “The Oxford Book of English Verse” has been on the shelf since 1999. It remains pristine, the dust jacket unscuffed, the spine still creaking with the unlimbered resonance of the new book. What can we say of a world where the treasures of knowledge and insight that make us fully human are available to everyone in every place no matter how insignificant and yet remain unsullied by use and therefore unbroken by love? What can we say of such a world other than that it is tragic and harrowing?

We live at a unique point in human development. We reside at the intersection of a hedonistic culture that promotes an ideology of individual pleasure above all and views the subordinating of lower pleasures to higher ones as a kind of soul-suicide and a technological revolution that makes every possible pleasure immediately available, the lower the better.

Technology has made every kind of media, edifying and degenerate alike, ubiquitous. Just as Mr. Ricks' wonderful volume is available in the remotest rural village in a neglected region, so is the basest of pornographies. It is a competition Mr. Ricks is bound to lose, and with him, all of us.

A time defined by the mass pursuit of the lowest pleasures is, by definition, dark.“Well,” you might say, “people have always been low. The world has never been populated solely by literary critics, even less by saints.” And you would, no doubt, be correct. What marks our times as dark is not simply that the masses prefer their pleasures lower, but that now everyone does.

In the “not-so-dark times,” our cultural institutions carried the torch. If the guy down the street preferred TV to Tolstoy, at least we could trust that someone somewhere felt differently on the matter. These days, we can’t be sure. Passion for what made the soul of the West has dimmed, its vibrance diminished by the vehemence of the relatively few who hate it, but even more by the contagious empathy of everyone else.

And yet the flame remains unextinguished. Some smoldering ember remains, forgotten on solitary shelves in unglamorous places. There, it is considered to be safely quarantined, unlikely to catch fire and burn to the ground our current cultural settlement. And this is the good news, for what is forgotten has a good chance of persevering unmolested.

So long as the shelves are not emptied everywhere, the possibility of a less dark future lingers. Let us hope the warm coals of what we once were remain bright just long enough to attract a new band of devotees who might arise, even in some obscure locale, to kindle the flame of our heritage anew.