All photos courtesy of Kelley Lamy

Camille Lamy was unjustly smeared as a 'racist' by the women charged with protecting and educating her. Her parents are still waiting for an apology.

On the last morning of Teacher Appreciation Week, 5th grader Camille Lamy arrived at Bridge Point Elementary in a black, short-sleeve T-shirt from Nordstrom and black shorts from Free People.

Walking away from her mom’s black SUV, Camille spotted some of her classmates, who were also clothed in black. Earlier that week, the class had to choose between gray and black as their team color for “May Madness,” the school’s year-end extravaganza. Camille voted for gray.

The two other 5th-grade classes chose orange and blue. All the students, every grade, were color-coded. There was a stream of kids in all pink, one in all yellow.

In her April 28, 2023, “Bobcat Bulletin," Bridge Point principal Sheri Bryant had added a note of caution to the otherwise celebratory mood of "May Madness": “SUNSCREEN IS A MUST FOR THIS DAY!!”

Principal Bryant, who also serves as the diversity, equity, and inclusion representative for all elementary schools in the Austin, Texas, Eanes Independent School District, urged parents to “apply sunscreen the morning before school and send some ... to reapply before activities begin.”

As Camille walked into school, her sun-screened face blended in with all the others. It must have been an odd sight: unicolored lines of children, many glowing with what almost appeared to be whiteface, on a day that would erupt into accusations of blackface.

By the end of “May Madness,” even Camille’s blue monkey, Roller Rabbit, one-piece bathing suit would be stained black. But not her face — it would be blotched red. Neither white nor black.

During an interview in December 2023, Camille’s dad, Jay, balked, “Should the blue team apologize to the Smurfs?”

This entire scandal is fraught with irony. The educators who rant about systemic oppression have become functionaries in a new system of oppression.

Bridge Point Elementary is tucked into the hills outside Austin, Texas, not far from a snaking bend of the Colorado River. Bridge Point is one of six K-5th grade schools in the Eanes Independent School District, commonly ranked as the best public school district in Texas and one of the top in the country.

Beneath this excellence, however, ideological tensions have been bubbling. And not just in Austin, Texas — it’s happening all across America. The scandalization of Camille Lamy provides what the Lamy family lawyer later described as “a subtle glimpse at the rot overtaking the institution of education, increasingly overtaken by an archaic system hellbent on gathering victims for their enigma.”

The three Bridge Point educators who cornered Camille — Bryant, homeroom teacher Mollie McAllister, and substitute teacher Katelyn Joane Schueller — are all true believers in the mission.

It’s no coincidence that, at the board meeting that saw Bryant approved as Bridge Point principal, parents decried the district's laxity with “banned books,” a euphemism for sexually graphic material. Principal Bryant is part of the next wave of radicals who champion porn in public school libraries as a victory.

My guess: She’s young, and she’s just getting started, and her ideological temperament won’t change. At this point, she can’t change it, even if she wanted to. Because her primary function is to normalize and package DEI and anything like it. This is not a secret: The “Parents” section of the Eanes ISD website links to a portal dedicated to DEI.

Bridge Point guidance counselor Rachael Sherman’s website, likewise, touts the benefits of the Social Emotional Learning method, a social science fad that has made its way into school curricula; an Orwellian policy that amounts to social engineering; a fashionable learning model presented as a virtuous process that claims to elevate “social and emotional learning” to the level of traditional educational subjects like science, arithmetic, and reading.

Behind the empty academic jargon hides a theory worth rejecting. At its core, it’s a platform for school officials to co-opt duties and beliefs and decisions that belong to parents. It’s a dereliction of the principles and responsibilities that society has afforded educators. But what exactly is "social-emotional literacy"?

It clearly focuses on racial ideologies and radical gender theory. What does an emotionally and socially literate child look like to these educators?

The accusations against Camille are intentionally impossible to refute. That Camille had no intention of donning "blackface" — or, for that matter, that her appearance barely approximated "blackface" — doesn't matter. Nor does Camille's record. By all accounts, she's a good kid: bright, respectful, clever, friendly. Prior to this, she had never been sent to the principal’s office.

The younger kids went outside for May Madness first. The older kids, including Camille’s class, were scheduled for the afternoon.

When Camille and her classmates arrived in their classroom, their usual homeroom teacher Mollie McAllister wasn't there. This wasn’t exactly terrible for Camille, who had felt a weird hostility from McAllister for most of the year, seemingly in response to her father Jay's recent campaign for a spot on the school board.

In McAllister’s place was Schueller, a highly educated and well-traveled white woman in her early 30s. She had never substituted for Camille’s class before, nor did she know Camille.

According to the June 6 rebuttal from the school district, the class was unruly all morning and eager to manipulate their substitute teacher, wandering the room freely as they insisted that McAllister had told them May Madness day would be pure recreation, without any schoolwork.

Amid the chaos, one of Camille’s classmates, a girl, pulled out a tube of eye black, the oily face paint first popularized by Babe Ruth as an antidote to blinding sunshine.

The eye black was dispersed exactly how you’d expect in a room full of 5th graders on a Friday, with a substitute teacher, right before having a literal field day. The students rubbed it under their eyes.

Before long, they grew more adventurous. Some of them graffitied themselves.

This is where the story gets tricky, because none of the students took pictures, and the school has taken the unusual step of removing any posts related to this year’s May Madness from its website.

In one version, Camille and another student, a boy, covered their faces with the eye black, calling to mind the ... colorful theatrics of Al Jolson.

This is unlikely, in part because eye black is extremely difficult to remove — I tested it on my arm.

Camille says that she had never seen eye black before and only put some on her forehead, cheeks, and chin, although she painted stripes on her arms and scribbled a monkey on her leg — which is apparently a reference to her nickname.

Schueller then told Camille and the boy that they “could not have eye black on their faces.” Camille insists they did not understand why.

The school district’s account epitomizes DEI logic, reporting that the eye black “concerned Ms. Schueller because of the race-based implications of blackface.”

Schueller then “took the opportunity to explain to the students that it can be seen as offensive to people of color when non-black people paint their entire faces black.” In fact, she “saw this moment as a learning opportunity rather than a disciplinary situation."

According to Camille, Schueller told her and the boy, “I know your intent was not to be racist, but what you did was racist.”

At the word “racist,” Camille and her classmate rushed to find towels or napkins to remove the eye black from their faces but could only find toilet paper — public school toilet paper isn’t made to survive any kind of vigorous wiping.

Camille says that the toilet paper only agitated her skin, without removing the black paint. I tested this, and it holds up.

Schueller then sent Camille and the boy with an escort to the principal’s office. They were directed to wait in Sherman's office.

Principal Bryant took them into her office separately. The boy went first. Ten minutes later, Camille.

As she waited, Camille remembers Sherman, one of only two black staff members, walking past her repeatedly, saying nothing. Something about the way Sherman looked at her left her feeling ashamed and embarrassed and confused.

The demand for proper blackface scandals exceeds the supply. Activists seeking one are not above lowering their standards; the criteria for guilt have dropped well below the level of blackface that is public and spiteful. Cases in point include the California middle schooler who faced a ban from school sporting events for wearing eye black and the 9-year-old football fan in face paint who a Deadspin journalist harassed and sought to humiliate.

On the rare occasions that children have actually worn blackface, it was initiated by an adult. In one case as a botched attempt to celebrate Black History Month.

Why, then, is the persecution-driven activist class so willing to accuse children — wrongfully — of racism via blackface?

Conversely, why do they overlook actual instances of blackface from their own political ilk? And not children, mind you. Adults, fully aware of their choice, like any one of the heavy-handed, BLM-chanting types — Justin Trudeau, Sarah Silverman, Jimmy Kimmel, Jimmy Fallon, more — who have been exposed for past use of especially inflammatory blackface, only to evade consequences.

And we’re talking egregious caricatures, even full-body black paint, with accompanying voice and gestures.

Their duplicity and sanctimony expose one type of amorality prevalent among the activist class, to which the above-mentioned staff, and celebrities, belong: If blackface is truly heinous enough to haunt Schueller when accidentally displayed by an 11-year-old, how can the activist class ignore the rampant, public, intentionally offensive instances of blackface among their peers?

The racial demographics of the area surrounding Bridge Point are paradoxically ideal for this sort of politics: wealthy families, in the scenic West Lake Hills of Austin, who are as liberal as they are white.

So, the school’s population is overwhelmingly white, a whopping 75%, much higher than the state’s 26%. Meanwhile, a paltry 0.3% of the students are black, which is significantly lower than the statewide figure of 12.8%.

The Texas Education Agency 2022-23 STAAR Performance rating seems to indicate that for the 2022 school year, there were so few black students in Camille’s class that the results of testing could not be shown in order to protect their identity.

The staff demographics are roughly the same, with 2% African American and 79.8% white. Statewide, African Americans comprise 11.8% of the teaching population.

There are 47 equivalent full-time teachers and one full-time school counselor. Most are women.

A staff climate survey from 2022 determined that the majority of staff believe that “students at school are treated fairly regardless of their backgrounds and differences.” None voted “strongly disagree.”

There was less agreement on the prompt, “I feel comfortable facilitating an in-depth conversation around diverse topics in my classroom,” with only 24% selecting either “agree” or “strongly agree.”

According to the Texas Education Agency 2022 Federal Report Card for Bridge Point, there were zero recorded incidents of harassment or bullying on campus that year.

After ten minutes, Bryant came for Camille. In her office, she told Camille, “I know your intent wasn’t to be racist, but you were being racist. You could have offended other adults in the building. What you did is called blackface. That’s offensive. You need to wipe your face off.”

Note the emphasis on offensiveness. She rebuked Camille for having approached the possibility of offending an adult staff member — which, based on the demographics, with two exceptions, is most likely a white woman.

The June 6 rebuttal states that the reason Schueller and Bryant were concerned with removing Camille’s face paint was that they wanted “to prevent others at Bridge Point from taking offense based on a misperception that students were wearing blackface.”

Bryant gave Camille some wet wipes for her face. Camille says that, at this point, her skin was visibly inflamed from all the futile wiping.

Bryant didn’t mention Camille’s face, but said, “You need to apologize to Ms. Schueller.” Then, she said, “Tell me what you’re going to say.”

Bryant forced her to rehearse an apology:

“I’m sorry for what I did.”

“And what did you do?”

“I’m sorry for being racist.”

“That’s good.”

The Eanes ISD denies that Bryant referred to Camille, or any other student, as racist: “In her opinion, Camille was simply overzealous with the application of the face paint without realizing that painting one’s face black could be perceived as carrying with it the history of blackface.”

School administrator Molly May, in one of the reports, claims that the council did not “find that either adult intended or even attempted to manipulate Camille, and I do not find that their efforts to aid Camille’s understanding as to the reason it was advisable to remove the black paint from her face was done for purposes of manipulation or to achieve some sort of personal advantage.”

Ten minutes later, Bryant dismissed Camille, who claims to have seen Sherman “soothing” Schueller in the hallway. This dynamic is telling: It’s ridiculous that both women would classify the “kind of blackface” event as traumatic; but it’s even more outrageous that the white liberal woman would be the one in need of consoling, from a black woman, who, counselor or not, is catering to the politics of an adult over the safety of a child.

Moreover, the whole blackface hysteria was contrived by Schueller to begin with. So, she was — allegedly — sobbing in response to her own misplaced outrage at a scenario of her making.

Camille says that she passed by them without making eye contact, then went to the cafeteria for lunch. Her classmates, puzzled that Camille would be in trouble, quizzed her about her trip to the principal’s office.

For the rest of the day, Camille ignored Schueller. She kept her head down until the final bells rang and kids rushed through hallways, then she walked back to her mother’s black SUV and told her everything that happened.

Like an excellent plot-twist character, McAllister returned to Camille's homeroom the following week and made things even worse.

After Schueller described the previous Friday’s events, McAllister was rather unhappy. Apparently, her students had gotten all minstrel-show with some eye black?

The school board insists that Schueller neither mentioned racism during her conversation with McAllister, nor “that she thought any students were being racist," adding that Schueller felt she’d resolved the situation and no further action was needed.

McAllister refused to leave it at that.

Camille insists that when McAllister rebuked the class for their "misbehavior,” she made a point to pause theatrically on Camille and her classmate in crime.

Ms. McAllister chided her class for having “acted poorly for Ms. Schueller and [taken] advantage of Ms. McAllister’s absence — including by over-applying face paint on their faces and bodies.”

Notice the recurring mentions of Schueller being emotionally damaged by the children, or, worse, deeply offended.

Camille claims that, after demanding apology letters, McAllister took away her iPad, the implication being that McAllister wanted to keep Camille from documenting the letters but also still wanted to punish the children.

In hearings, McAllister claimed that “she did not directly address Camille or any other student about the racial implications of blackface.”

The school district’s report is full of DEI nonsense, high-flown language about how the teachers, the counselor, and the principal all practiced remarkable wisdom in transforming a crisis into a learning moment — lived experience and all that.

The school district has repeatedly stated that “Camille had no intent to cause offense to anyone on the date of the May Madness event” and that “no Eanes ISD employee involved in this matter believes that Camille is racist or that she knowingly acted in a racist matter.”

These phrases could easily be attempts to mask their harassment of their young charge. A claim that their aggressive social-emotional session was simply a learning opportunity for everyone involved -- the kind of thing with which parents need not concern themselves.

If this weren't a disciplinary matter, why did authority figures need to get involved?

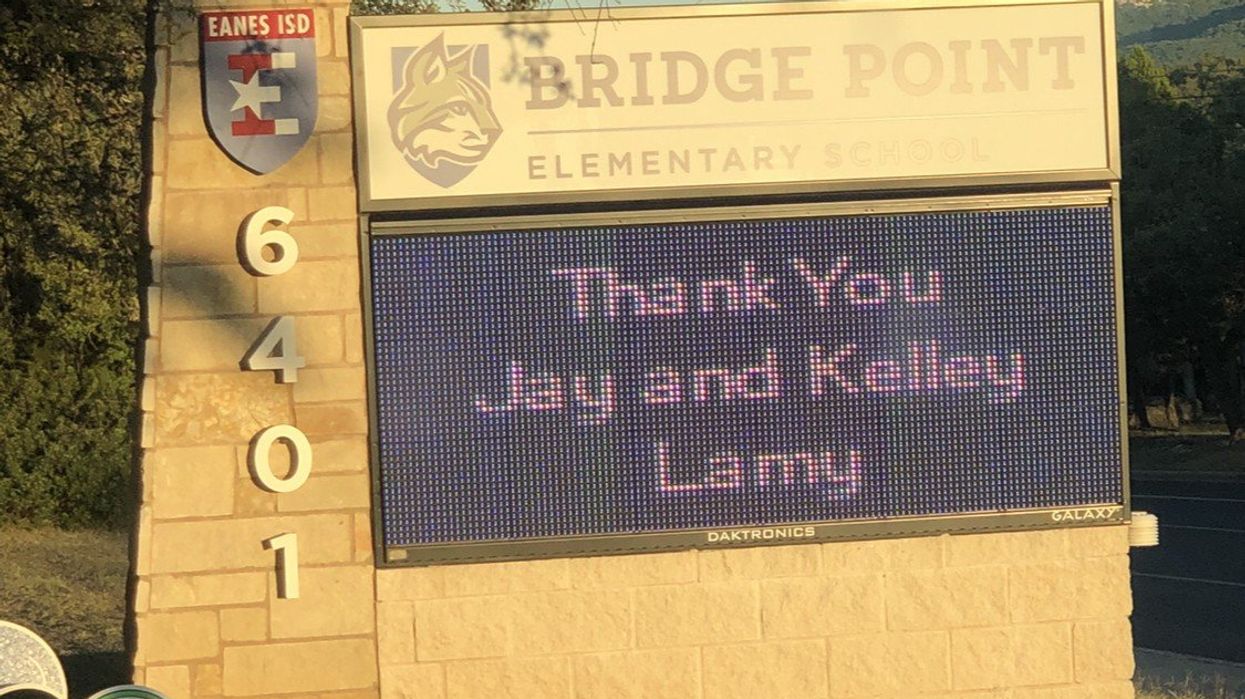

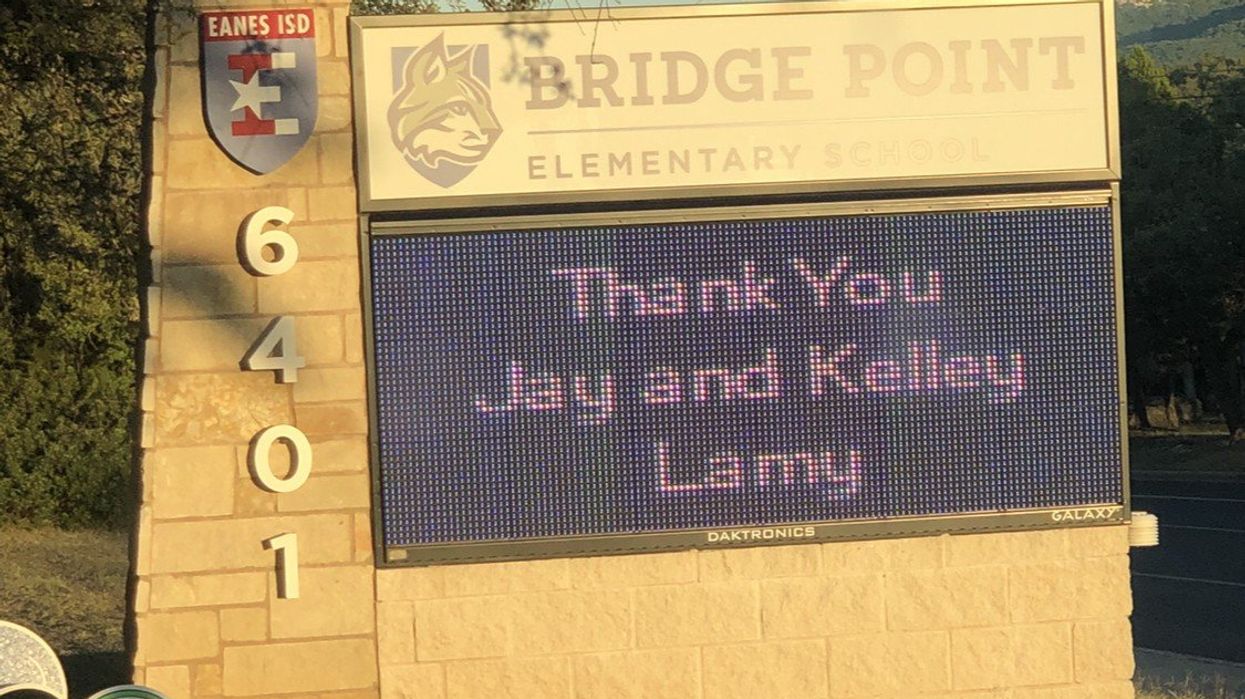

This head-spinning ordeal led Jay and Kelley Lamy on a journey through the twisted bureaucracy of the public school system. Late May, they submitted what’s called a level one complaint. “All we want is an apology.”

The school said no.

So, the issue was elevated to the top school board, which voted 7-0 for NO APOLOGY.

Their lawyer Stuart Baggish says that the Lamys want “complete relief from any shadow of an accusation that their daughter Camille Lamy is a racist. She is not a racist.”

The district removed any references in Camille’s permanent record that “in any way related to her purportedly being racist, purportedly acting in a racist manner, and/or purportedly engaging in conduct connected with or constituting racism.”

Schueller — who Baggish refers to as the “woke white woman” — seems to have instigated the entire crisis. What does that signify?

According to her Facebook page, Schueller studied “Elementary Education” at Purdue University, before a stint in Chicago public schools, then began as a 1st-grade teacher at Eanes ISD in August of 2017.

Like many Americans, in July 2020, she changed her profile picture to include a Black Lives Matter frame. Which is not in itself significant, but it hints at her suspected political leanings, which likely obeys an ideology that demands race be the focal point of any interaction.

Allegiance to this mode of thought would explain Schueller’s eagerness to hunt for racist behavior and her subsequent hysteria — if that is, in fact, what happened.

The rundown from the school district’s Level 2 response on June 20 states that Schueller told officials that “she was moving away from the Eanes ISD area and that she would no longer be a substitute teacher for the District in the upcoming school year.”

The now 34-year-old seems to want to move on from the scandal.

Camille's mother, Kelley, “heard from another mom that Schueller left teaching full-time to get her master’s. So ... she may still be teaching in Texas at some point in the future.”

Her social media accounts have all been scrubbed. But around the time of the incident, her Instagram bio read, “Character is how you treat those who you can do nothing for."

In 2013, Schueller was profiled by Ozaukee Press, a weekly newspaper in Wisconsin, about her third trip to Swaziland as part of a nonprofit program to build schools for children orphaned as a result of AIDS:

“Whenever they have free time, the volunteers visit the orphans in their homes. They planted avocado and fruit trees in their yards so the children can eat fresh fruit and installed solar panels on some of the houses.”

The risk with scapegoating is that the scapegoaters can easily become the victims in need of defense.

Because Schueller, like Camille, is also someone’s daughter.

Her father, a retired CEO and founder of an energy company, now blogs about a variety of topics and seems to be a decent guy, interested in political cohesion. Her grandma posts sweet things on random Facebook pages.

Maybe roasting her on a conservative news outlet will only worsen the situation.

Because maybe she’s a victim of ideology, too. Sure, it’s not the same. Camille is an innocent victim, while Schueller is an adult with a teenager’s politics. And, either way, a privileged activist really shouldn’t be in charge of teaching children anything.

But making her the replacement scapegoat only shoves the injustice to the political nobodies on the other side. The true villain is the system that taught her to hunt for victims of her own.

Right?

Not quite. Compassion is lovely, but not if it spurs injustice. The truth is simple: Each individual child is more important than the entire education system. The system is foremost structured to protect children, to ensure their well-being. The activist class that has embedded itself in the education system has reversed the order. To them, the system is what purifies and absolves, and children are the unformed citizens in need of social, emotional, political, and even sexual liberation.

From their affluent white enclave, the all-female, melanin-challenged staff of Bridge Point Elementary pump their fists like Black Panthers.

And yet, they still can’t clarify the simplest contradictions in their logic. And if I’ve grown repetitious on this point, then I’ve succeeded in capturing the unanswerability of their sloganry.

Is racism universal? Is it objective? Where’s the limit to what’s racist? Who is included in the pool of suspects?

Why does the activist class defend the race-bait manipulation of Harvard President Claudine Gay, yet an 11-year-old girl is within the borders of castigation?

What are the rules?

More important, who is exempt from these social mandates and their severity? Who is allowed to invoke exceptions to them?

We have our answer, strengthened by the account above: They only make exceptions for themselves. This is their biggest slipup of all. Because it reveals their character, willing to mistreat the most vulnerable.

In Matthew 18:6, Jesus declares that anyone who scandalizes a child might as well tie a millstone around his neck and drown in the depth of the sea. It's a verse that the officials who bullied Camille Lamy would do well to remember.